In the quarter-century since New Labour’s grand constitutional experiment began, politicians in the devolved legislatures have refined several vexatious, but undoubtedly effective, rhetorical tactics for deflecting criticism and undermining the UK.

For domestic audiences, they blame any shortcomings in their governance on Westminster, and insist that the solution is even more power for themselves. And when politicians in London bestir themselves in their own defence – an all too rare occurrence – the devocrats invariably pretend that any criticism of them is a criticism of the country they run.

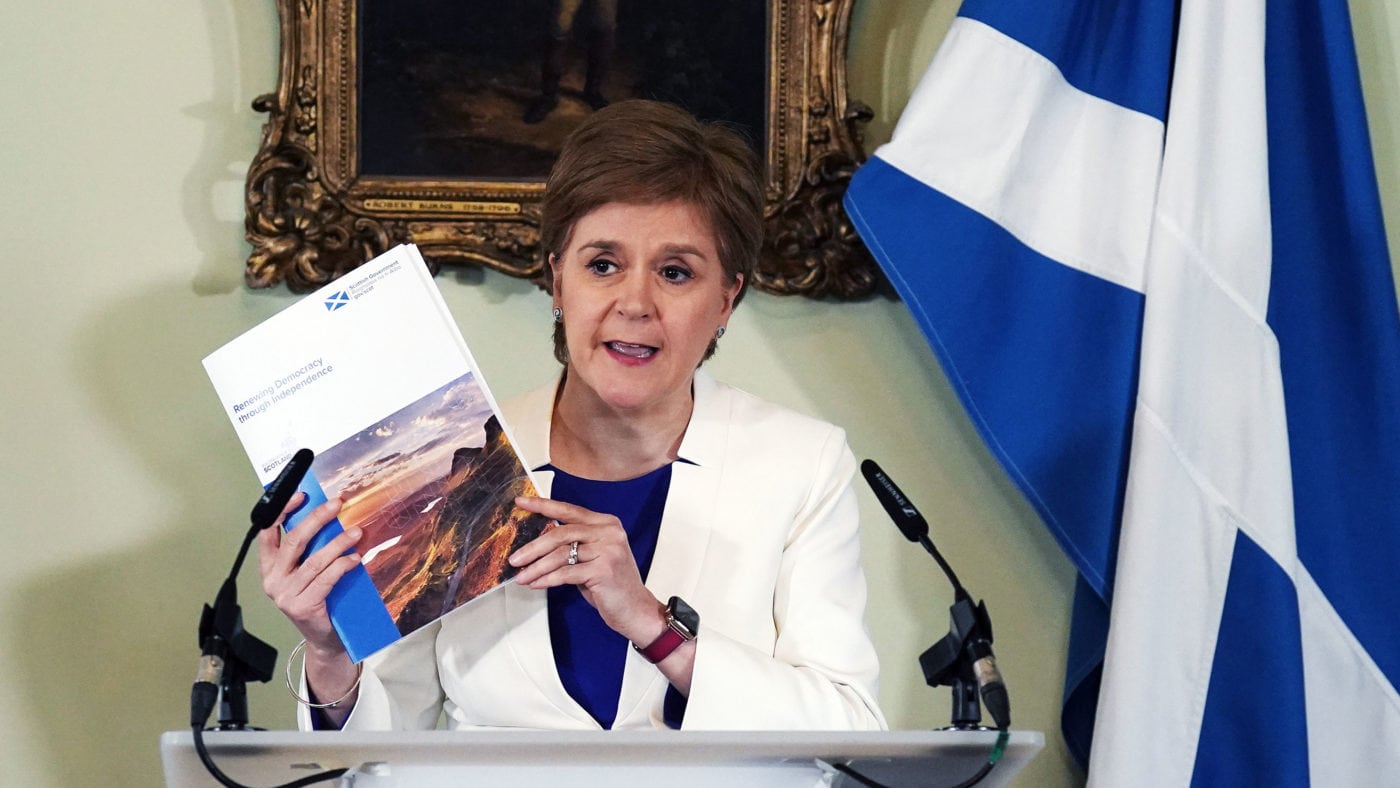

We saw this bizarre form of lèse-majesté in action after Liz Truss, speaking at a Conservative leadership hustings in Cardiff, branded Nicola Sturgeon an ‘attention seeker’. This rather genteel criticism was presented, not just by Nationalist partisans but elements of the press and commentariat, as an attack on Scotland and her people.

The charge is nonsense, of course, and to his credit even Anas Sarwar, the leader of Scottish Labour, has said as much. (He might want to have a word with his Welsh colleagues, who previously accused Michael Gove of ‘invincible colonial attitudes’ after he had the temerity to compare English and Welsh school outcomes.)

But the backlash is a reminder of the skewed playing field the next prime minister will be navigating when it comes to taking on the SNP – and ought to serve as an indicator of what an effective form of ‘muscular unionism’ (if we are to use the term) looks like.

As my scare quotes indicate, the phrase ‘muscular unionism’ was coined, in the great British political tradition, by people who don’t like what they claim to be describing. We should therefore be careful with it. But if we were to summarise the position it is supposed to label, it would be ‘speak loudly and carry a small stick’.

When commentators claim that Boris Johnson’s government attempted a muscular unionist approach, this is what they mean. It basically describes a policy of stonewalling the nationalists and devocrats’ demands for referendums or powers and striking a belligerent public posture (which, as above, is often not distinguished from merely ‘attacking opposing politicians’).

This undoubtedly inadequate approach – we could not really call it a strategy – is contrasted with orthodox devolutionary unionism, with its emphasis on saying only nice things about devolved politicians, pretending they’re good-faith governance partners who want a functioning United Kingdom, and restructuring the constitution accordingly via endless concessions, in the hope that the centrifugal forces unleashed by New Labour will eventually dissipate of their own accord.

Suffice to say, this binary is false. An effective ‘muscular’ unionist strategy consists of speaking softly whilst wielding a very big stick: Parliament and the British state.

Perhaps the most obvious example of doing this was the UK Internal Market Act. This legislation is sometimes overshadowed by Brandon Lewis’s comments about breaking international law – in a ‘specific and limited way’ – in relation to Northern Ireland. But it also gave the Government substantial new powers both to maintain the coherence of the British internal market against devolutionary divergence and to increase the footprint of the national government in the devolved territories.

This fact wasn’t lost on the nationalists and their outriders. But attempts to rally Scottish and Welsh voters on the issue were a damp squib. Voters don’t seem particularly invested in the fine detail of the devolution ‘settlement’.

What both Truss and Rishi Sunak need, therefore, is a proper programme for both using the powers granted by UKIMA to expand the role of the British state in the lives of citizens in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, and to give serious thought to further legislation Westminster could enact to build a stronger, better-operating UK.

These don’t need to be big, noisy, set-piece battles where Mark Drakeford and Nicola Sturgeon can pretend the entire devolved order is under attack. So broad is the scope of their powers at this point that London can afford to pick and choose its battles with some care.

An obvious place to start would be something like mandating the collection of uniform national statistics to allow for proper scrutiny of devolved governance, and ending the bizarre situation wherein the Scottish Government can effectively opt out of a coherent national census. This is the sort of detail work which could have big, long-term dividends and is unlikely to decide the vote of anybody not already deeply invested in the nationalist cause.

In other cases, the Government could pick a noisier and more obvious political battle, but on winning terrain.

Any legislation enacting the recent Union Connectivity Review should, for example, repeal the provisions of previous legislation granting the SNP the power to pursue their deeply unpopular plan to abolish the British Transport Police. A joined-up national transport network needs a joined-up, national police force.

These are just a handful of examples; every department should be tasked by whoever ends up in charge of Union policy of producing their own list. The remorseless pursuit of such a programme – without gratuitous rudeness to the devocrats, no matter their provocations – is what a proper unionist strategy looks like.

You will note that it is looks quite different to merely ‘ignoring’ the enemy, as Truss suggested she would do. Both Sarwar and Rishi Sunak recognise this would be a bad idea. We must hope the Foreign Secretary comes round to the same view.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.