Imagine a system that can translate the will of the people into instant action. No more waiting for elections. No more filtering democracy through legislators and regulators. Instead, a question will pop up on your phone. Should maternity leave be more generous? What should the new royal yacht be called? We’ve found a senior ISIS leader hiding next to a school. Should we kill him?

In Dave Eggers’s 2013 novel “The Circle”, this system exists. Called “Demoxie”, it’s the ultimate expression of the hive-mind society he fears we’re becoming: one that lets its users not just change the world, but change it “at the speed that our hearts demand”.

Four years on, many of Eggers’s concerns seem eerily prophetic. There’s the increasing demand for absolute transparency: to scrutinise everything from our children’s exam results to our politicians’ shabby deals in real time. And the mob mentality: the way in which the wisdom of crowds is often less apparent than their self-reinforcing stupidity.

But what Eggers got wrong was simple. Digital technologies are not, in fact, welding us together. They are breaking us apart. The online world is increasingly a conflicted, chaotic and caterwauling place, in which each self-selecting tribe is ever more insistent on its own demands and ever more dismissive of others’.

The internet has enabled revolutions in Egypt, broken open the monopoly of entrenched voices and parties, and fuelled a re-engagement with politics in all its forms. At the same time, it has helped dictatorships monitor and influence their citizens, led to a collapse in authority and hierarchy, and empowered the purveyors of bigotry and prejudice.

If economics is ultimately about allocating finite resources to infinite wants, then politics is ultimately about making sure everyone is happy with the results. And this is why digital technologies have been both the best thing to happen to politics and the worst. They have made the demands more insistent, and the allocation more contested – and at the same time, more necessary than ever.

The internet has not been around for long, but it has had a profound impact on how we think and communicate. The evidence is that it does not so much change who we are as intensify it: in particular, by pushing our natural tendencies to self-segregate into overdrive.

This problem is made worse by a well-known propensity of online communities – and communities more generally – to become more extreme as they become more isolated. To fit in with a group, we adjust our opinions and our enthusiasm to fit the perceived consensus. And online, because we cannot see the other members, we tend to assume they are just like us – and therefore terrifically nice and clever and trustworthy.

Tim Harford, in his new book “Messy”, tells the stories of the Eagles and the Rattlers – two tribes of boys at a summer camp who were induced by social scientists into foaming hatred of the others within a matter of days.

The experimenters managed to persuade the boys to settle their differences. But there’s no such paternal supervision online. Within weeks of expressing mild interest in a political candidate (or a TV show) we find ourselves becoming a super-fan, defining our identity in terms of our new passion.

This social splintering, it is increasingly clear, is not a product of particular national cultures, but a universal side-effect of digital technology.

The recent US election, for example, brought a great flurry of interest in “fake news” – the fact that enterprising teenagers in Macedonia were circulating stories about Donald Trump being endorsed by Denzel Washington, or Hillary Clinton having sold weapons to ISIS. A 27-year-old from Glasgow convinced the editors of the right-wing conspiracy website Infowars that outtakes of Trump using the N-word on The Apprentice were about to be released, simply by messaging one of its editors.

Nor were these stories only being peddled at the margins. The most popular fake story, claiming that Pope Francis backed Donald Trump, got more Facebook shares than any election story published by the BBC, New York Times or Washington Post.

These stories took flight not because they were convincing, but because they reflected people’s propensity to believe what they wanted to believe: they did not cause the segregation, but amplified it.

You can see this phenomenon across the world. When India demonetised, conspiracy theories spread via WhatsApp that the replacement notes would contain RFID chips to track the population. In South Sudan, unsubstantiated reports of tribal slaughter, and calls for vengeance, fly back and forth.

In a digital space, it is easy to mimic credible sources – or to pass on hearsay as fact. And the problem will only get worse: soon, faked audio and video will be almost as easy to produce as the real thing.

Worse, given that the stories we see are those that our friends have shared, or that are similar to those we have clicked on already, we won’t even have to ignore the other point of view – because we won’t even see it in the first place.

The glory of digital technologies, and their curse, is the way in which they act to give us exactly what we want.

Donald Trump, Jeremy Corbyn, Beppe Grillo and so many others have succeeded by finding and motivating those previously excluded from the conversation. But allied to this, there has been a collapse in authority and hierarchy. An age where the consumer is king is also one, as Avner Offer reminds us, where kings are no longer needed.

It was not just that Trump and Corbyn used digital tools to build their movements. It was that they and their followers defined themselves against the mainstream media, and mainstream politicians – those established hierarchies still built around an old-fashioned sense that people should listen to their betters.

This phenomenon has been entrenched by changes in media consumption. We used to consume news via newspapers, or TV bulletins – bundles of what editors thought we should read. These might have had an ideological slant. But their need for advertising pushed them towards a mass circulation model, and hence towards the mainstream.

Now, just as the album has broken down into individual songs, consumed via playlists, so has news broken down into individual stories, consumed via social media streams.

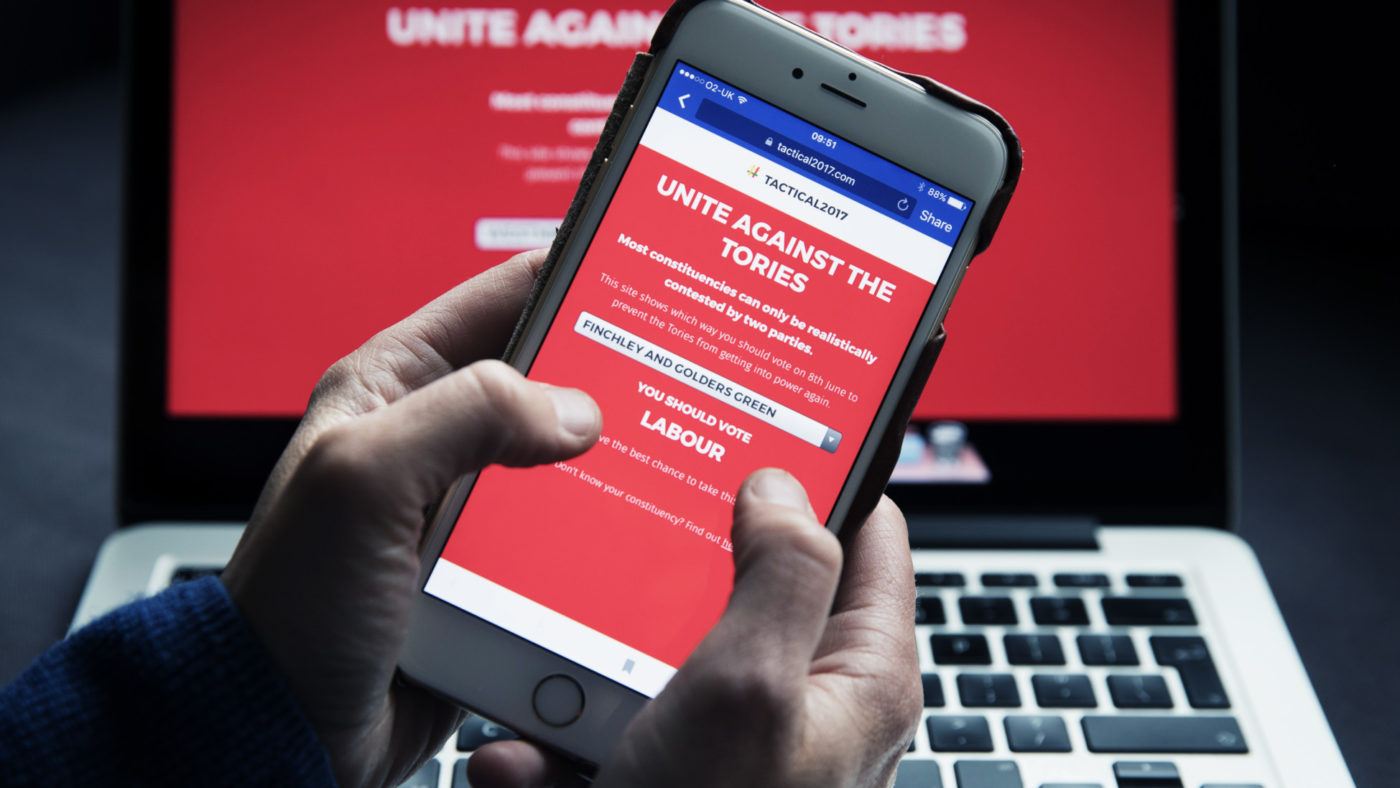

Political campaigns have shifted to match this era of personalisation. Borrowing the techniques and increasingly the datasets used by advertisers and supermarkets, they segment voters into all manner of niches – then micro-target their messages, using psychological profiling to determine not just the issues to raise but the tone to use. One consequence of this, seen in many recent campaigns, is that the national narrative about the state of the campaign, or the polls, is essentially beside the point.

Society is becoming splintered and fractured. But there is another force at work: the way in which digital technologies are not just pulling society apart, but speeding it up.

Looking back on his career recently, Sir Jeremy Heywood, the head of the British Civil Service, admitted his routine is now “breathtakingly different”. The reason? That things are moving faster.

In the old days, he said, you would write out a policy submission. Then you would send it downstairs to be formally typed up, before it was placed on your superior’s desk. He would then make comments and corrections, which would be sent downstairs for more typing, before the document was either sent back to you or passed on up the line. Some days or weeks later, a minister might actually see it.

Today, there is no printing office in the basement, no time for policies to percolate their way up the chain of command. Ideas zip around departments via email or text message – with even junior staff chipping in with their thoughts.

As I wrote in my recent book on the topic, this acceleration is not bad in and of itself. But in politics, it contributes both to hasty decisions, and to a more general overloading of the timetable.

The speeding up of the news agenda – itself a product of digital technologies – means that politics has got much, much faster. Where once there would be a single big story per day, now there can be five or six. Donald Trump sends out a tweet, and competing algorithms race to buy or sell shares that might be affected. Some traders in Mexico City worked out that it would be cheaper for their nation to buy and close Twitter than to cope with the battering in the markets every time the impulse struck the President to tweet about his big, beautiful wall.

Trump is, of course, the epitome of the accelerated, impulsive age. But even Barack Obama found that the acceleration of the news agenda creates an insistent, incessant pressure to react, to respond – that horizon-scanning inexorably turns into fire-fighting. Gordon Brown’s ministers recall how his government became paralysed in the glare of the media spotlight, with BBC News playing on one wall of the Downing Street war room and Sky on the other. Ted Sorensen, speechwriter to JFK, judged that if the Cuban Missile Crisis had happened today, the public and media pressure for immediate action would have resulted in a disastrous pre-emptive strike.

The culmination of this is to strip away what our governing systems were erected to sustain: the role of deliberation and delay.

Edmund Burke may not have been a popular man when he told his constituents that he owed them his judgment rather than his obedience, but he had a point. The explicit idea of representative democracy is that the kratos of the demos is expressed through those representatives.

Now, however, there is an increasing sense that the popular will – in all its fickle volatility – is all that matters. Witness the increasing reliance on opinion polls to dictate policy, or the opprobrium directed at the British judges who dared to have an opinion on the constitutional status of Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty.

This, indeed, is another paradox of the digital age. Technology has made information more widely available than ever before: if you want to make yourself an expert in something, you can. Yet the premium placed on knowledge and authority has been whittled away: the “experts” are merely another self-serving cadre. What started as a welcome breath of fresh air through the corridors of power has turned into a hurricane.

Digital technologies have rendered politics relentlessly centrifugal, by both splitting society apart and speeding it up. They are fuelling a society in which the guiding theme is that we should refuse to settle for anything less than what we want, when we want it.

Yet they are also transforming society, and the economy, in other ways. America has lost five million manufacturing jobs since 2000 – primarily due not to Chinese competition, but advances in automation. Such digitally enhanced productivity is simultaneously producing greater wealth – and a boom in highly specialised, highly skilled manufacturing jobs. How to reconcile the winners and losers? And how to bring about equality of opportunity in a society where algorithms imbued with human prejudices show higher-paying job adverts to men then women, or falsely flag up black people as criminals at twice the rate of white?

Part of the answer – the cure for the disease – must be to identify the positive aspects of digital technology, and build on them.

There has been much work done on ways in which digital technologies can improve the delivery of public services. Technologies such as crime mapping help use police resources more effectively. A team of just 80 people was able to roll out an ID card system covering India’s billion-plus population. And the British government’s Digital Efficiency Report found that digital transactions are 20 times cheaper than phone calls, 30 times cheaper than sending forms through the post, and 50 times cheaper than face-to-face meetings.

Digital technologies can also enable people to organise themselves, rather than relying on politicians. One British MP notes how appeals from parents of disabled children, previously a huge part of his caseload, dwindled as they began to organise and support each other online.

They can also give people a powerful platform to make their voices heard – and to engage them in policy-making. In particular, they make it easier to expand decision-making beyond those in power, for example by opening up public data sets or spending decisions.

The British government, for example, still lives in a world in which ministers take home their paperwork and go through it with a pen and a glass of wine – an antiquated system from an antiquated age. Contrast that with the cities in South America where decisions are made via participatory budgeting – a process that builds community by trusting it.

In starting to formulate solutions to these problems, there can be no turning back: the eggs cannot be unscrambled, the jar cannot be unshattered. Any answers which start by rewinding the clock to an imagined golden age are doomed to disappointment.

For Eggers, the nightmare scenario was one in which politicians effectively became stars of a 24/7 reality TV show, wearing cameras and microphones which broadcast their every move, their every shady discussion and shabby deal, to the public.

Yet in an age of corrosive scepticism about politics and politicians, the only response can be to make it clearer than ever that there is nothing to hide. After all, evidence shows that while people distrust politicians in general, they tend to have far greater faith in their own representatives – those whom they have seen in action at close hand.

When it comes to the great problem of self-segregation, companies such as Facebook and Google are currently in the position of Stanley Baldwin’s harlot: they have power without responsibility. They need not just to take a far firmer line about identifying outright fake news, but to make people aware in ways large and small that they are seeing the world through a distorted lens – by flagging up misleading or partisan content, or simply by indicating to readers that other views exist.

But we cannot, and should not, rely on Mark Zuckerberg to rescue our democracy. We also need an intensive process of education: to teach people in classrooms and universities that what they consume on the internet is not, in fact, the unvarnished truth. On this score, there is much to learn from research into deradicalisation: how do you best persuade people to change what they sincerely, though erroneously, believe?

Ultimately, however, the truth is that it is politics that must adapt to digital technologies, not digital technologies to politics. There is no rebuilding the traditional two-party system, or the days of deference and hierarchy in which everyone clusters around the evening news broadcast to be told what to believe.

In every age, politics reinvents itself according to the dictates of the dominant communications technology. Ours is no different. If people are scornful and cynical about politicians, it is partly because the structures and practices of politics do not do enough to promote transparency.

So if they demand a say, let us give them one – with the proviso that they are asked not to vote just on the biggest issues (whether Britain should leave the European Union, say), but on the smallest ones.

And if people distrust the decisions made by national or supra-national governments, let us try to devolve those decisions to the local or individual level – to provide points of engagement rather than points of blame.

It is not just that, as Amartya Sen says, people become fit through democracy rather than for it. It is that there is nothing the ideologue likes less than being asked to contribute their constructive views on the detail.

Above all, we need to rebuild the deliberative function of government – but this time, as a more collaborative exercise. “Demoxie” is a horrible system, but it speaks, like the fake news stories that swirl around the internet, of a prevailing belief that government is not of the people and for the people, but something done by “them” to “us”.

One of the great lessons of the digital age is that when people are actually brought together – when they are forced to engage with each other as human beings – their common humanity re-emerges. The same person who has been writing vicious anonymous slanders on Twitter will still squirm with embarrassment when meeting his victim face to face.

We need to create forums, both online and off, where that can happen – and, more audaciously, to confer on them enough real power to make the exercise worthwhile.

None of this will fix everything that is wrong with politics. In an age when conspiracy theorists can link a pizza restaurant to a child pornography ring to senior members of the Democratic Party – and mount an armed “investigation” – we are clearly through the looking glass.

But ultimately, the only way to contain the damage wrought by digital technologies is to stop looking to rebuild what we have lost, and start thinking about how to build something new – and perhaps even something better.