“Seven million Britons in poverty despite being from working families,” laments the Guardian. “Housing crisis ‘creates in-work poverty’,” reports the BBC. “British workers living in poverty ‘at a record high’,” thunders the Independent.

If you read the headlines, you could be forgiven for imagining that Britain has entered a new age of Dickensian misery.

We were already bewailing the fact that real wages have been stagnant for a decade. Now we are told that the meagre salaries on offer aren’t even enough to keep millions of our fellow Britons in food and lodging.

The poor used to live in fear of Mr Bumble and his workhouse; now they tremble at the footsteps of the branch manager at Sports Direct.

But this narrative – of what The Observer calls a “relentless slide towards a low-pay Britain” – is wrong. In fact, it’s worse than wrong. It’s dangerous.

Let’s start with the basics. It is obviously very much not ideal that real wages have remained stubbornly low since the 2008 crash. Yet as Tim Worstall pointed out on CapX last week, much if not all of that is cyclical rather than structural – a way of adjusting to post-boom reality without the wrenching job losses seen in Europe.

Moreover, when we talk about the level of poverty that this has produced, we need to remember that we are generally talking – as with the latest report from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and New Policy Institute – about something that is as much a social as an economic construct.

Get more from CapX

Follow us on Twitter

Like us on Facebook

Sign up to our email bulletin

The JRF/NPI report, for example, has all sorts of statistics about the poverty rate. But its actual definition of poverty is when a household’s income (net of income tax, National Insurance, etc) “is less than 60 per cent of the average (median) household income for that year”.

What we’re talking about here, in other words, isn’t absolute poverty but relative poverty. It’s not that millions of people are unable to put food on the table. It’s just that they can afford to put less food on that table than everyone else.

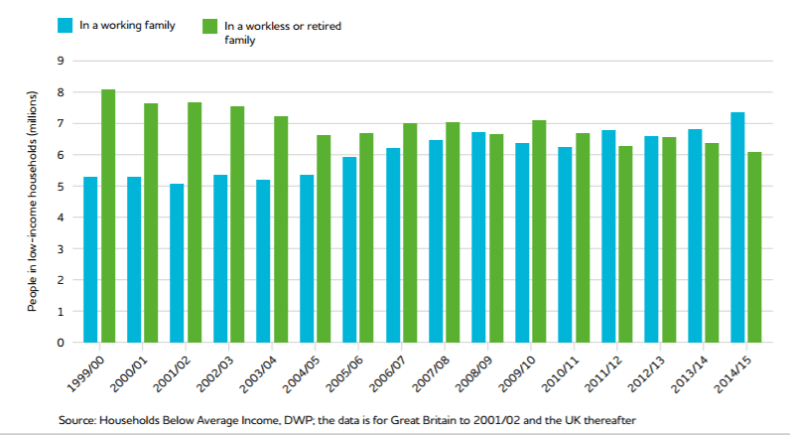

And as this chart shows, even though poverty – or perhaps “poverty” – has been rising among working households, it has been falling among the jobless and retired, to the point where the proportion of people falling below that (arbitrary) 60 per cent figure has remained roughly constant (in fact, it has fallen by 300,000 since the Tories entered Downing Street in 2010):

The JRF/NPI report also contains some other statistics which suggest that this situation may improve. The proportion of working-age adults in employment is at a record high. Youth unemployment is the lowest since 2005. In such a tight labour market, wages are likely to increase – if a bit too late for many of our taste.

But the really important thing about the low pay debate – certainly about the coverage of it in the media – is that it ignores the fact that it is actually on the rise.

In 2015, George Osborne replaced the minimum wage, for workers over 25, with a National Living Wage (NLW). That has meant that, over the past year, those on the minimum wage have had a pay bump of more than 10 per cent.

Yes, there were changes to the benefits system that clawed some of this back. But the increases aren’t going to stop there. Osborne also committed the Government to raising the minimum wage, by 2020, to 60 per cent of the average salary.

Precisely because there is such a broad consensus about Britain being a low-pay economy, and higher pay being good, there has been virtually no discussion of quite what an ambitious – and potentially risky – strategy this is.

On one level, of course, it simply represents a transfer of the pay burden from the state to the private sector. The Government currently spends £30 billion a year topping up wages via tax credits: the overall effect of raising the minimum wage will be to force stingy employers to bear much of that burden.

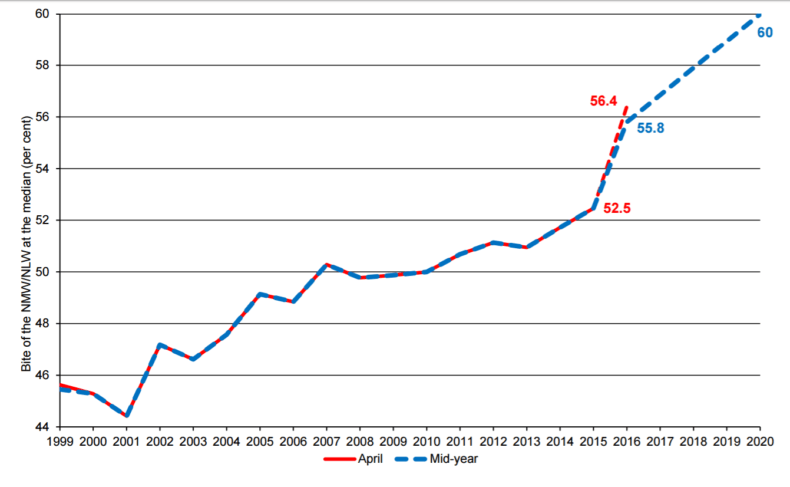

But committing to the 60 per cent target, says the Low Pay Commission, which sets the level of the NLW and evaluates its impact, means that “the pace of increase in relative pay for minimum wage workers aged 25 and over will be the same 2015-2020 as for the period 1999-2015 – a rate of growth three times faster than previously seen”.

When the minimum wage was brought in under Tony Blair, it was set at just over 45 per cent of the average salary.

Hiking it to 60 per cent will, says the LPC, leave Britain with “one of the highest minimum wages in the world” – even allowing for the fact that the target figure has been reduced from £9.16 to £8.61, partly to take account of the uncertainty surrounding Brexit.

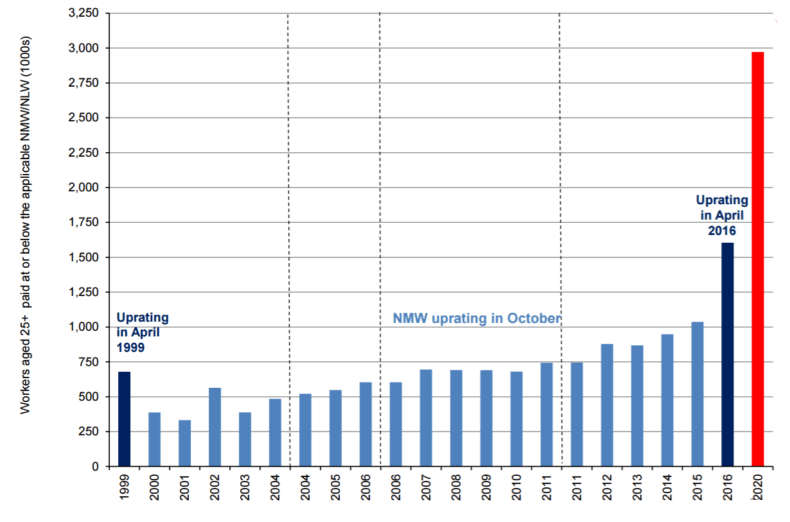

The obvious consequence of this is that the minimum wage will affect an awful lot more people.

Back in April 1999, as this next chart shows, the rate was set at a point where it only affected those on absolutely miserly pay – well under a million people, or 3.4 per cent of the labour market.

The LPC estimates that by 2020, one in six private sector jobs will be paid at a minimum wage rate. That’s an enormous expansion of its scope.

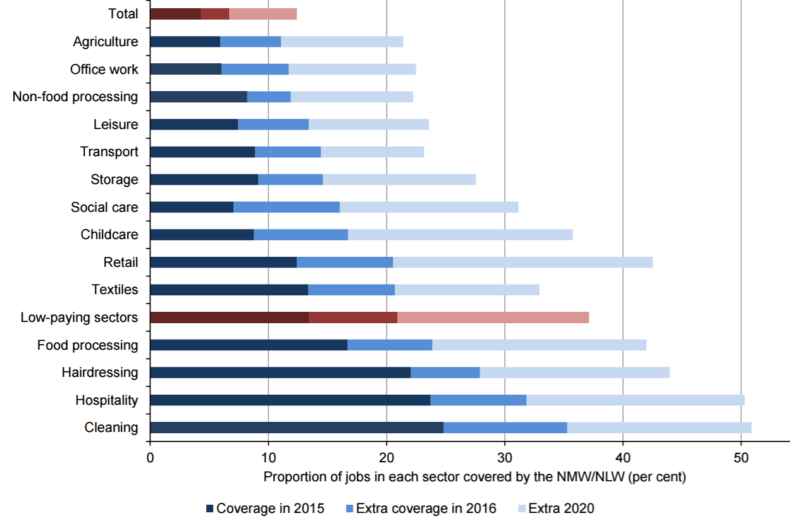

And of course, not all industries – and salaries – are created equal. There are some industries in which almost nobody earns the minimum wage. There are others in which almost everyone does. And they are, as this next chart shows, going to see a vast expansion in the proportion of their workforce affected by the minimum wage.

This is, says the Government, part of its plan to move Britain “away from a low wage, high tax, high welfare society and encourage a model of higher pay and higher productivity”.

Which is all very well. But can you really bring about a high-wage society by fiat?

Basic economic theory would suggest that increasing the minimum wage will depress job creation.

Firms facing an increase in salary costs will be less likely to make new hires, or will cut the hours of existing workers – or will move jobs to other, lower-wage countries, or will invest in labour-displacing technologies (such as robots) that can do the same job more cheaply than the suddenly-more-expensive humans.

Also, to put it bluntly, low wages (at least compared to our big European rivals) have long been one of Britain’s competitive advantages – especially given the shortcomings of our education system.

It’s not just about employment. Firms faced with higher costs might simply pass on them on to the consumer via higher prices, making their staff richer but the rest of us poorer. Or there will be a growth in black- and grey-market activity, as more deals are done off the books and under the table – or in the kind of abuses seen with zero-hours contracts, as unscrupulous bosses do everything they can to evade the extra costs.

And there will almost certainly be an increase in immigration: if tens of thousands of Eastern Europeans are willing to come and pick strawberries at current wage levels, imagine how many others will be tempted as the minimum wage climbs higher.

It was precisely these kind of fears that led the Blair government to tread so carefully when introducing the minimum wage originally.

There is a widespead consensus now that these fears were overblown: since 1999, the British economy’s job-creating powers have shrugged off any harmful effects from the minimum wage.

But there must be a point where the harm outweighs the benefits – and the current serial increases make it all the more likely that we will reach it.

As the LPC’s analysis says, the minimum wage “is delivering substantial gains in pay to workers but also presenting challenges for employers”.

“Low-paying sectors including horticulture, textiles and convenience stores” have already reduced working hours, recruitment or employment – and have serious concerns about what will happen as the rates ratchet up.

The Association of Convenience Stores, for example, warned back in 2014 that a majority of its members were already laying off staff – a majority of those because of increased employment costs.

The Commission’s most recent report includes a comment from the CBI calling the Living Wage hike “a real stretch” and “out of step with pay growth in the lower-paying industries and the economy as a whole”.

The most affected sectors, it says, are “generally labour-intensive, low-margin and price-taking sectors where the challenge of paying higher wages is compounded by little room to pass on increases in costs to customers and limited scope to boost productivity in the near-term”.

In written evidence to the Commission, “care providers reported to us that their medium-term sustainability remained at risk, with many facing losses and some reports of withdrawal from contracts. Data from the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services in England record that 32 councils had residential care contracts handed back in the six months to May 2016, rising to 59 councils for home care.”

Elsewhere on CapX

The trouble with the Chancellor’s productivity blueprint

Britain needs to upgrade its benefits system

Does diplomacy matter any more?

Similarly, “the horticulture sector warned that high wage costs are a serious threat to the sector, with the NLW (on its March 2016 forecast path) risking profitability towards 2020. The childcare sector in England was concerned about the interaction of higher wage costs with increased free hours – a ‘tipping point’ which could squeeze margins, reduce quality and increase fees to parents.”

Of course, such complaints are only to be expected: no business was ever cheerful about paying more to its staff.

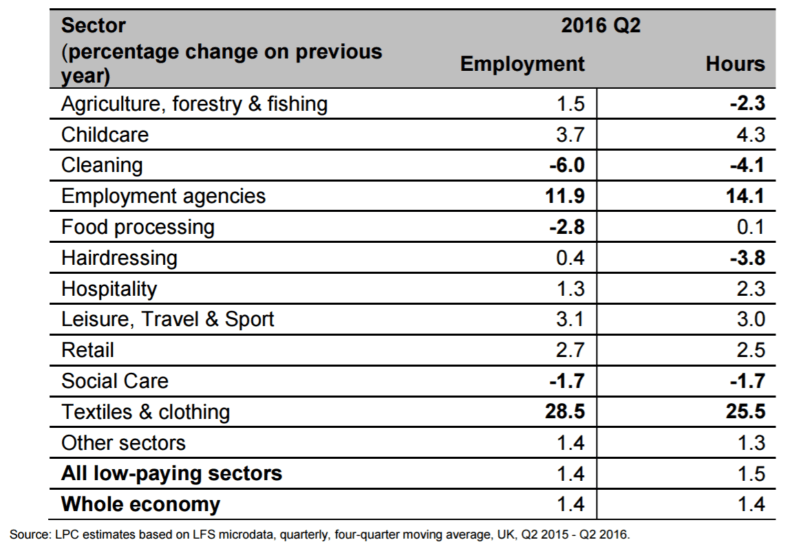

Yet already, there is some indication of a squeeze. Prices for “minimum-wage” goods (ie the kind bought by minimum wage earners) have indeed increased by more than the national average. Employment in many low-paying sectors, as this chart shows, is indeed lagging the rest of the economy:

There are clearly too many people in this country whose wages are too low – as witnessed by the fact that the state has to spend billions topping them up.

Yet the 60 per cent benchmark has all the hallmarks of the “triple lock” on pensions. It’s the kind of policy which, once entrenched, is devilishly hard to amend or abolish, because doing so is seen as an act of wanton cruelty. It becomes the natural state of affairs, even if the evidence turns out to show that it’s doing more harm than good.

In April 2017, the National Living Wage will go up by another 4.2 per cent – and then it will go up again, and again.

That seems, on the face of it, like a very good thing. Yet there may well come a point where we find that forcing up wages isn’t a recipe for ending poverty, but increasing it.