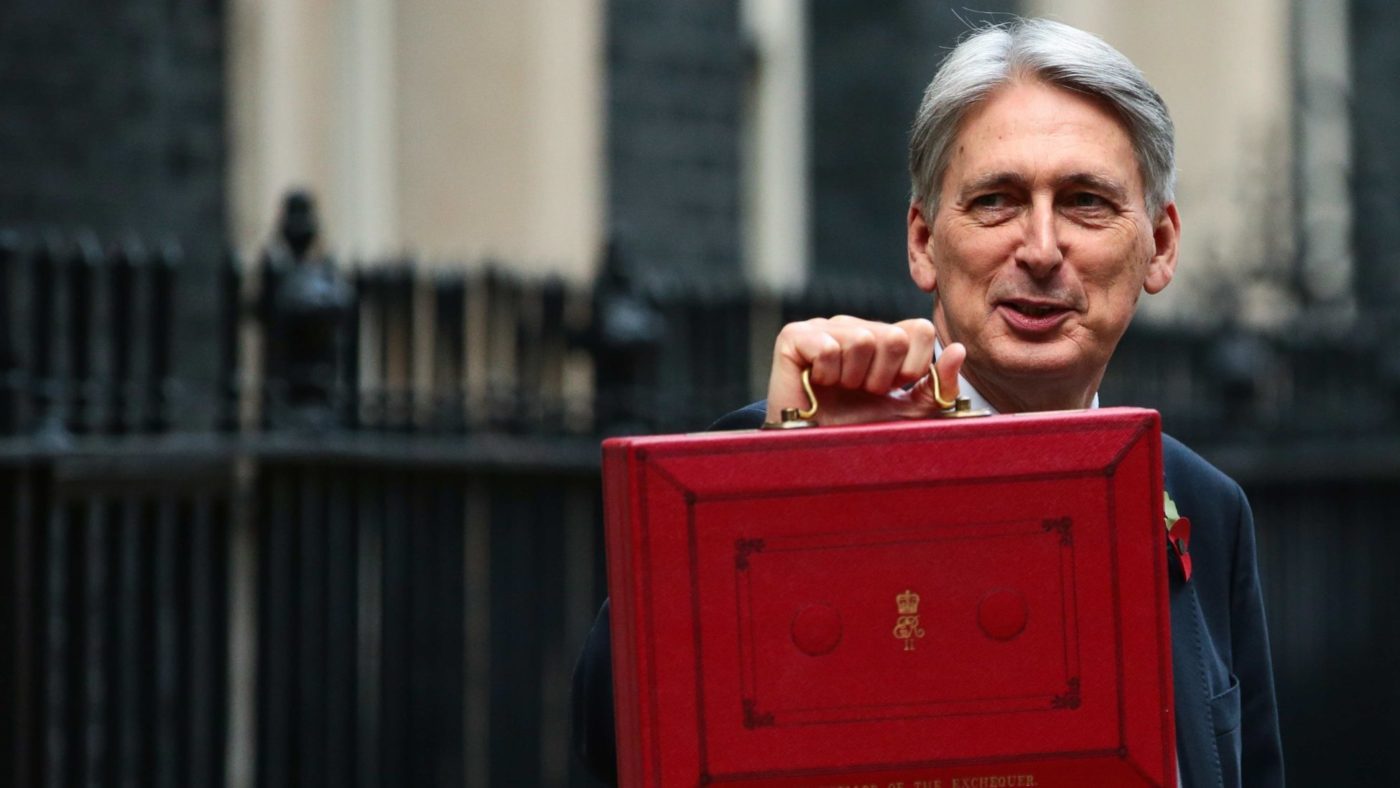

You could be forgiven for not having noticed, but on Wednesday the Chancellor delivered his Spring Statement.

This is essentially just a response to the biannual fiscal updates which the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) is mandated to issue, giving its assessment of the health of the economy and the public finances. True to his word (and Spreadsheet Phil persona), it was a sober affair. The revised forecasts for growth and borrowing were set out, a couple of relatively small spending announcements were made, a few reviews reported back, but on the whole it was all pretty dry.

But beneath all that, something very important is happening. A little later than first planned, the Chancellor confirmed that the government will conduct a Spending Review over the summer, to report back alongside the Autumn Budget. With everything else that’s going on, it might seem difficult to get excited about a review of departmental budgets. But Spending Reviews are actually massively significant for our politics and the direction of the country, and this year’s will be more important than ever.

The Spending Review will draw the outlines of the political agenda for years to come, but it will also come at a watershed moment for British politics. By the autumn we will (we assume) have officially left the European Union, and though there will still be negotiating left to be done, MPs and ministers will finally be able to return to domestic policy, and think about what vision they want to pursue for post-Brexit Britain.

Not only that, but for the first time since the financial crisis more than a decade ago, this Spending Review will not have fiscal consolidation as its main object. Causes for optimism might seem few and far between to some people right now, but the public finances have been consistently outperforming expectations, and the government is set to meet its deficit and debt targets for 2020-21 pretty comfortably.

That is an achievement for which credit should in no small part go to the last two spending reviews. It’s worth noting that of the 7.4 percentage points that have been wiped off the deficit-to-GDP ratio between 2010-11 and 2018-19, 6.6 have come from reduced spending, and only 0.8 from higher government receipts. That is a significant achievement. What’s more, if uncertainty around Brexit has dissipated sufficiently, the Chancellor will also be able to use some of the fiscal headroom he has been saving up to guard against the risk of rainy days ahead.

On top of all that, the current set of ‘fiscal rules’ run out in 2020. The Chancellor will probably set himself a new fiscal mandate for the coming years when he delivers the Autumn Budget and Spending Review.

All of this means that, as ‘Fiscal Phil’ emphasised in his speech this week, we will finally have the freedom to make “real choices” as a country about our priorities for the future. First of all, it means deciding what path to pursue for overall spending, borrowing and debt. From what he said on Wednesday, it seems likely that the Chancellor will maintain the objective of having debt falling as a percentage of GDP on an ongoing basis. With debt at such historically high levels, he may question whether simply having that figure falling, even if only marginally, is enough; might he, for example, set a specific numerical target for the debt-to-GDP ratio by a certain year? Currently it is forecast to fall by more than 10 percentage points between now and 2023-24.

And will there still be a target to eliminate borrowing entirely? The current stated aim is to do so “by the middle of the 2020s”. While the best commentators (including the IFS) have been saying for years that this seemed nigh on impossible without even further retrenchment, the forecast deficit for 2023-24 is now just 0.5 per cent of GDP, and that has been revised down by 0.3 points just since October, so maybe a surplus is not such an unrealistic prospect after all. The real question is whether the Chancellor will choose to pursue this, or whether he will instead decide that he is happy with the situation we are broadly in now, where we are running a surplus on day-to-day spending but borrowing relatively small amounts to invest.

Of course, in reality all of those questions depend on the choices we want to make about our priorities for the future. When it comes to domestic policy, the main political artillery which the opposition parties currently have at their disposal is strain on public services and welfare. With the government now hoping that its large spending commitment on health last year has removed that thorny issue from the top of the political agenda, schools, police and local government are next on the list, and they are rising up the lists of voters’ concerns in the polling. Pressure is also rising around welfare reforms and the introduction of Universal Credit.

As well as all that, there are wider, long-term issues to deal with, such as an ageing population and the pressures it will place on the social care system and on pensions, and rising demand for working-age disability support. Conservative MPs will also be keen to point out that the tax burden is at historically high levels as a proportion of national income, and with the decade-long policy of raising the income tax threshold to £12,500 coming to an end this April, they will want to know what the next big policy will be for letting working people keep more of what they earn (the Centre for Policy Studies has already made some suggestions).

The debates within government over what to do about these issues in the Spending Review will scout out the ground on which the Conservative Party will likely end up fighting the next election, even if that election is several years hence. With the Prime Minister’s (and with her Philip Hammond’s) political future currently hanging in the balance, those at the top of government will no doubt also be aware that the Spending Review and the vision it sets out will be a big part of their legacy to the country.

For a whole host of reasons, then, what the Chancellor says when he gets to his feet in the Autumn to deliver his Budget will be critical for the future of our politics. It’s very easy to get distracted by everything else that’s going on at the moment, and to ignore such mundane issues as the Spending Review. Do so at your peril.