For the Labour Party, robots are the new class enemy. According to media reports, Jeremy Corbyn has said that he wants companies that profit from replacing humans with robots to pay more tax. Another of his ideas is to put ownership of robots in the hands of employees.

Paranoia about robots is nothing new. The best known example is the Luddite movement of the early 19th century, when a group of English artisans protested against the automation of textile production by seeking to destroy some of the machines.

Yet historically, concerns around the impact of automation have been unfounded. Rather than being a negative development, the creative destruction brought about by new technology has boosted productivity, raised living standards and created new job opportunities.

It is not, however, safe to simply assume that the next stage of mechanisation will play out in the same way. The key concerns tend to revolve around two issues: job losses and the potential for growing inequality.

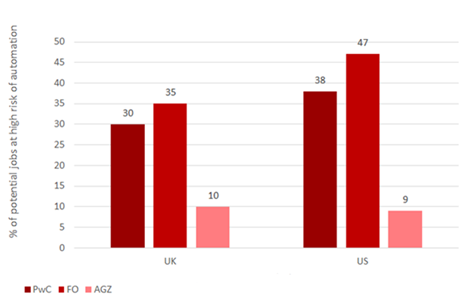

And yes, there will be job losses. Estimates of jobs that are at high risk of automation range from between 10 per cent to 35 per cent. But some perspective is needed.

Estimates of jobs at high risk of automation

Source: Pricewaterhouse Coopers

First, these figures are likely to be overestimates as they only consider the technological feasibility of a particular job being automated, not the economic viability. Second, there is strong evidence to suggest that the UK’s labour market will likely be less prone to the impact of mechanisation than many other OECD countries.

And finally, jobs are vanishing all the time anyway – every year, roughly 10 per cent of British jobs are destroyed, and another 10 per cent created. This is why PriceWaterhouse Coopers concluded that automation is likely to be job-neutral, at least over the next few decades.

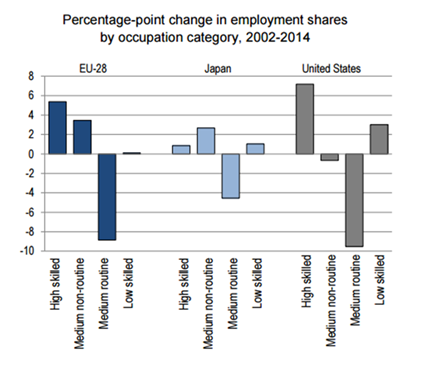

The second concern – about growing income inequality – merits greater consideration. There has, to some extent, been a “hollowing out” of mid-level skills across Western economies.

However, it is important to note that this trend has been observed far more strongly in the US than in Europe. There has, in fact, been a substantial growth in “medium non-routine” jobs in Europe. According to the Taylor Review earlier this year, the so-called “hollowing out of the middle” has not yet had an effect on wage distribution in the UK.

Job polarisation in the European Union, Japan and the United States

Source: OECD

Against these concerns, the benefits of automation could help transform the prospects for UK workers and the UK economy more broadly. Rather than simply replacing jobs, machines and Artificial Intelligence will increasingly help complementary roles to workers that can boost their productivity and allow them to focus on parts of their role that add most value.

The UK is particularly well placed to benefit from this transformation – and particularly in need of it.

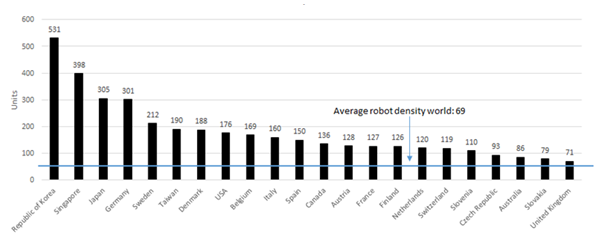

Britain currently has a very low capital-labour ratio, which is a key reason why productivity and wage growth have lagged behind our OECD counterparts. The UK has only 71 robots per 10,000 employees in the manufacturing industry, compared to 301 in Germany. This would suggest that, rather than being at risk from over-capitalisation, the UK is suffering from under-capitalisation.

Robot density in UK vs EU (per 10,000 employees in the manufacturing industry) – 2015

Source: International Federation of Robotics

Deliberately impeding mechanisation with the explicit purpose of “protecting jobs” – via Labour’s “robot tax” – would harm the UK economy’s progress. We are already behind the curve in terms of mechanisation, and labour productivity has suffered as a result. It is this low capital to labour ratio that has held back labour productivity, leading to muted wage growth since the financial crisis.

Taxing robots or legislating for robots to be in the ownership of employees would discourage investment in capital, exacerbating this problem. Rather than creating new jobs to compensate for ones that are lost to automation, it would see them go overseas, to the countries that have encouraged technological change rather than inhibited it.

In short, the robots aren’t going to throw us all out of work – but they might just make us better and richer workers.

Daniel Mahoney’s Why Britain needs more robots is published by the Centre for Policy Studies