It is no secret that the United Kingdom’s economy is imbalanced. London and the South East are head and shoulders above the country’s other regions with respect to economic indicators like gross value added per capita and median real earnings.

In a new policy pamphlet published today by the Centre for Policy Studies, we demonstrate how the capital and its surrounding region are also hoovering up the benefits of international trade and foreign direct investment.

It should come as no surprise to any ardent CapX reader that free trade and free flows of capital have beneficial consequences for an economy.

Ever since the likes of Adam Smith and David Ricardo refined the concept of comparative advantage, we have known that positive-sum gains can be made when economies export goods and services which they produce most efficiently, and import goods and services which they do not. While economists often revel in disagreement, on the subject of free trade enhancing consumer welfare they approve almost unanimously.

Crucially, the benefits of free trade and investment at a national level hold true at the regional level. On trade, for instance, data suggest that in regions which export more, workers are paid more, too. And given that in 2018 the UK sold goods and services abroad worth more than £634 billion – about 30 per cent of gross domestic product – it’s clear that trade has a huge impact on the relative prosperity of different parts of the country.

Ensuring that the UK has fit and proper trade and investment policies is therefore vitally important if the government is to make good on its mission to ensure that wealth and prosperity is spread more evenly across the whole of the nation.

The chart below shows up London and the South East’s dominance in sharp relief. Taken together, the two regions account for 43 per cent of the UK’s total exports – disproportionately more per capita than the rest of the UK. In fact, London alone exports about £15 billion worth more goods and services than six other regions put together.

We also found that this discrepancy plays out in terms of the number of businesses which export – with London and the South East again accounting for 43 per cent of all British businesses who sell products to people outside of the UK.

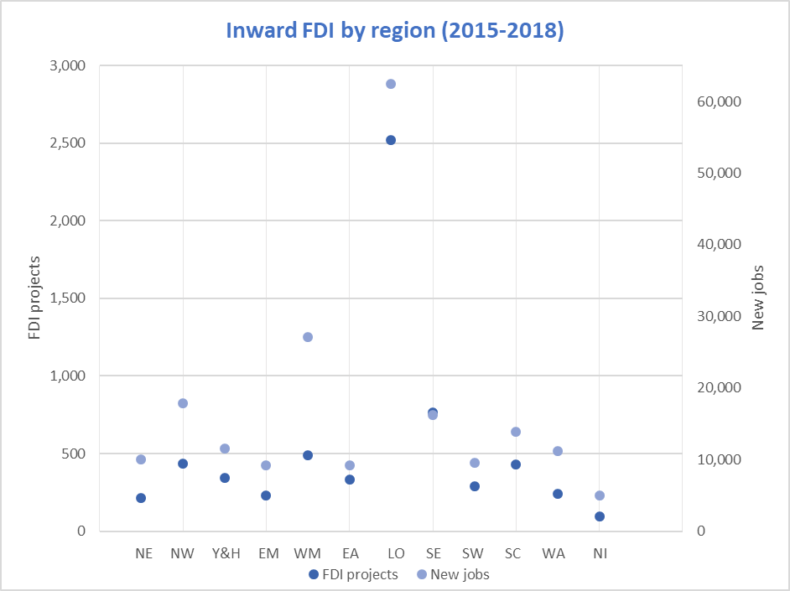

A similar picture can be observed with regards to where FDI ends up in the UK. We found that since the Department for International Trade was established and began compiling figures on FDI, London and the South East attracted over half of all new FDI projects, accounting for nearly two-fifths of all new FDI-generated jobs.

While other regions could point to some parity – both the West Midlands and North West actually enjoyed more FDI-generated jobs than the South East, although still attracted fewer individual projects – together, London and the South East nonetheless command a healthy lead as the UK economy’s outstanding powerhouse in this respect.

Plainly, much of the imbalance observed in trade and investment in the UK can be attributed to the underlying economic profiles of different regions. Of course London exports more, one might say, because it is fundamentally a far more economically successful region in the first place.

Be that as it may, yet this does not absolve the government completely. We believe that there are a number of pro-market ways in which Britain’s trade and investment policies can be improved – and, crucially, in ways which ensure that the substantial benefits of future trade reach across the whole country in a more balanced fashion than has been the case until now.

Firstly, if the Brexit debate has taught us anything, it is the importance of preferential trade deals. On this point, we argue that the government should drastically ramp up its trade negotiations with other countries in light of the UK’s pending withdrawal from the EU.

While the chattering classes often fixate on the merits and demerits of potential new deals with nations like the USA, what is arguably of much more importance is ensuring that existing agreements are rolled over. According to government figures released earlier in the year, just nine of 39 deals are due to carry over come 31 October 2019. Twenty-five are listed as “engagement ongoing”, while five “will not be in place” – including those with Japan, Israel, and Turkey, which collectively total £40 billion in trade with the UK.

Secondly, assuming the UK does leave the EU Customs Union and Single Market, the government should establish a number of ‘free ports’ across the country (something which the UK’s current EU membership precludes). Free ports are areas that exist within the geographic boundary of a country but are considered outside of the country for customs purposes. This means that goods can enter and exit the free port without facing import procedures or tariffs, and, if they were as successful as those in the USA, could deliver 86,000 jobs as a result.

Importantly, from the perspective of economic rebalancing, many of the areas where free ports would likely be created are among some of the poorest in the UK. In a 2016 paper, the CPS found that 17 of the UK’s 30 largest ports are in local authorities ranked in the bottom quartile of the Index of Multiple Deprivation – demonstrating that their introduction would likely be a boon for exactly the parts of the country which need them the most.

Finally, to boost investment into economically distressed areas, the UK should take another leaf out of the America’s book and establish opportunity zones. Like free ports, these are geographic areas of the country which enjoy special tax status to encourage individuals and companies to invest money into them, on the logic that it fosters business creation and supports employment. Indeed, we suggest that British opportunity zones could be even more enterprising – and experiment with other business friendly policies in such areas, for instance, simplifying taxes faced by small traders as laid out in a recent CPS report.

The recommendations above are just a handful of policies we suggest the government explores. Others we advocate for include liberalising immigration policy, reforming regulations to boost export finance, and simplifying the administrative procedures faced by existing or would-be exporters.

If the UK does ever manage to extricate itself from the EU, it will have the chance to craft an independent trade policy for the first time in almost half a century. This will almost inevitably pose threats and opportunities for the whole of the country. But, by adopting some of the policies we recommend, we are confident that it can ensure that any rebalancing which occurs as a result is because of a levelling up, rather than a levelling down.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.