Last week Kate Bingham set out her lessons for the government from the experience of the vaccine taskforce she led. Chief among these was a ‘lack of scientific, industrial, commercial and manufacturing skills both among civil servants and politicians’. She set out a convincing case for the civil service needing to do better at using science and scientists, but change will need political will and ministers prepared to commit to long-term reform.

The civil service needs more scientists but should prioritise using its existing talent more effectively

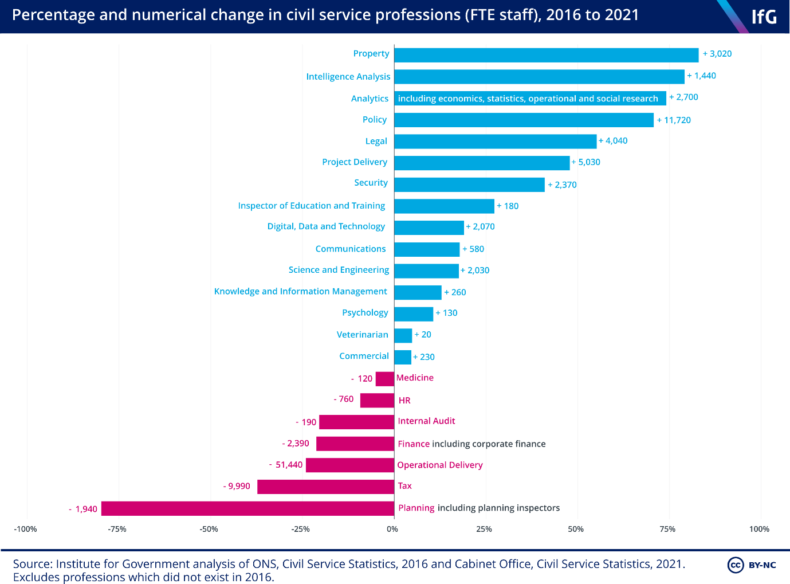

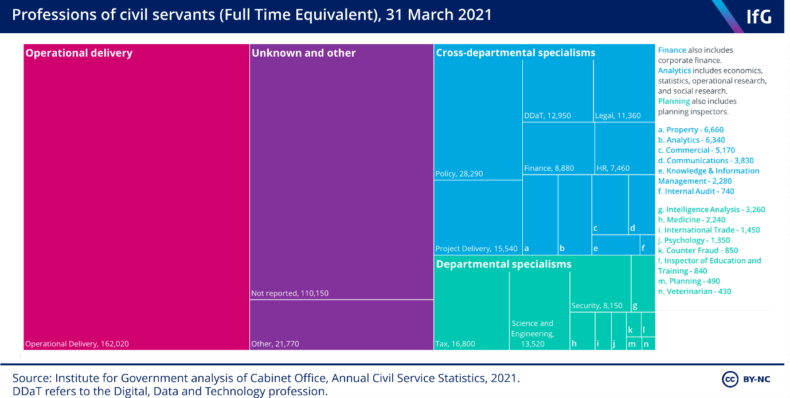

Bingham is right that both civil servants and ministers need to improve their scientific skills. Around 13,500 civil servants are members of the science and engineering profession. This did increase by 17% during the pandemic, up from 11,600 officials in 2019. But as a proportion of the total workforce, around 465,000 civil servants, it remains too small. And the science and engineering profession is growing more slowly than other disciplines. For example the policy profession, attracting more humanities graduates, has grown by over 70% since 2016.

Internal government data on the skills and experience of civil servants is also very poor, meaning that the skills of existing government officials with STEM backgrounds are not being properly used. A 2012 survey revealed that 40% of civil servants with scientific backgrounds felt their skills were underused or undervalued. Bingham is right to call for the recruitment of more people with these skills, but this should come alongside a more effective approach to deployment within departments.

Operational and delivery expertise must not be neglected

Bingham explained the importance of complementing the scientific and industrial expertise of outsiders in the vaccine taskforce with the project management, commercial nous and diplomatic experience of civil servants.

Government departments must recruit and develop people with a wide range of skills including scientists, project managers and commercial experts, as well as HR leaders, financial managers and communications specialists. Bingham is right to place a particular value on people with operational delivery experience.

That is why building multi-disciplinary teams will be vital to improving Whitehall policy making. Bingham presents the vaccine taskforce as a good example of this model. But more broadly Whitehall would benefit from a systematic approach to creating, deploying and managing multi-disciplinary teams. There is increasing evidence from all sectors that teams of people with diverse and complementary skills, brought together to work on a specific task, can substantially improve results.

Political will and long-term workforce planning will be needed

It is notable that Bingham referenced the critical role of ministers, echoing the Institute for Government’s view that ministerial training should be used to strengthen policy making.

Ministers have another role too – because the civil service reforms Bingham envisages will not happen without sustained political will. The prime minister has set out his ambitions for change in a ‘Declaration on Government Reform’, published last summer and which touches on some of the problems Bingham describes. But the Prime Minister and his cabinet colleagues will need to commit energy and financial resources to make reforms a reality.

For example, the Declaration commits the Government to introducing a model of capability-based pay for senior civil servants which could contribute to Bingham’s call for promotions, pay and status to be ‘based more on actual performance against substantive outcomes’. This is a welcome reform, but unless it is properly funded it will weaken civil service morale, and do more harm than good.

Finally, little will change in the skills mix of civil servants without a more sophisticated, long-term approach to workforce planning. In the recent spending review the chancellor set out plans to reverse the recent growth of the civil service and cut 45,000 jobs over the next three years, returning to the pre-pandemic headcount. But this is an arbitrary target, without the department-by-department workforce planning required to ensure that these cuts are properly targeted. To succeed ministers first need to invest in better data on skills, and use that data to develop a long-term workforce strategy to make reforms a reality.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.