Recently released Government housebuilding data contains a pleasant surprise – the number of new dwellings in England was over 241,000. This is the highest rate of housebuilding in England since the target for 240,000 new homes a year for the UK was set back in 2007.

This is good news for housing affordability, and national and city economies across the country. But it doesn’t mean the job is by any means finished.

This recent increase in construction has been driven by the private sector. Using a different data set (Table 222) which captures differences in tenure, the annual amount of new build homes finished in England has increased by 68% from the historic lows between 2010/11 and 2018/19.

Symbolically, this is important as it shows that a recovery in new market-rate housing is essential for addressing housing shortages. While there has been an uptick in council housebuilding in recent years, these initiatives are still gathering steam.

But this means that arguments such as that from the Local Government Association that a “genuine renaissance in council housing is the only way to boost supply [above 250,000 a year]” are incorrect. Supply has been boosted, without a major increase in development by councils.

New social houses target the benefits of new supply at lower-income households, and cities should have the powers and resources to deliver them if they so choose. But the priority area for reform to ensure that homes are inexpensive for everyone is market-rate supply.

However, while the new national housebuilding target of 300,000 a year is inching closer, questions remain. Most important is – where are these homes being built?

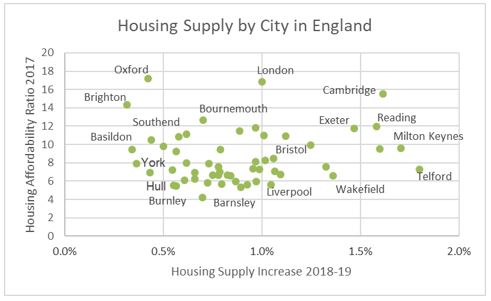

The chart below depicts the rate of supply over the past year along the bottom axis, and the housing affordability ratio in 2017 (the ratio of average house prices to local average income – higher is less affordable) along the side axis.

Some of our most expensive cities like Exeter and Cambridge are building new homes at quite a clip. But other unaffordable cities like Brighton and York are building very few homes – far fewer even than some cities where housing is much more affordable and where demand for new homes is lower, such as Burnley and Wakefield.

Not only does this damage the local and national economy, it also makes inequality and our Brexit divides worse. Not enough homes are built in Oxford, Brighton, or London to stabilise local houses prices in the long term. This means existing homeowners in these cities capture big increases in housing equity, while homeowners in cities with weaker labour markets see poorer returns. Since 2013, the average homeowner in Brighton has seen their equity rise by £83,000, compared to £5,000 in Burnley. How can that be fair in an economy which is supposed to reward hard work?

The problem is that unlike most parts of our economy, prices do not significantly guide where new homes are built, thanks to how our planning system rations land and controls development. Those new homes in Barnsley unfortunately do not do much for those facing sky-high rents in Oxford or those unable to buy in Basildon.

What this means is that to boost the economy, reduce inequality, and address the causes of Brexit, the next government should focus on not just boosting national housebuilding numbers, but on planning reform to ensure that those new houses are located in the cities with the highest demand. Switching from discretionary permissions to flexible zoning would rewire our planning system so that once a local plan is in place, development can occur unless the local authority explicitly says ‘no’, rather than forbidding any development until the local authority says ‘yes’.

Most of these extra homes have been built by private developers. But this has been possible thanks to the great deal of attention housing has received in our political environment. Among others, the rewriting of the NPPF and the development of housing targets; the push to get local authorities to create local plans and set out a five-year land supply; the creation of Homes England; the attempts to negotiate Housing Deals with local authorities; and Help to Buy are all examples of this.

The impact of these policies has varied, but they show that housing has been an important political priority. This reflects how unaffordable homes are given the housing shortage, and how it limits the ability of any government to enact its agenda.

Significant political capital has been expended to implement these policies. Under our current planning system that might even be necessary. But what happens if these policies are successful and housing affordability improves?

If a satisfactory supply of housing is contingent on significant policy support from government, then if housing becomes more affordable and its political salience declines, those very policies which support housing supply will become harder for government to sustain. In other words, the success of these policies will undermine their own rationale, risking future housing shortages.

To solve the housing crisis in a sustainable way then, the supply of new homes has to be driven by market conditions, not by whether or not housing is a political priority in Westminster. This would require a less politicised and contentious planning system, such as the Japanese model of flexible zoning, where development can proceed once it has been agreed in the local plan. If policymakers don’t manage to make this shift, housing policy in the future will eventually find itself back to square one, despite the hard work of everyone today.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.