Over the Christmas week, CapX is republishing its favourite pieces from the past year. You can find the full list here.

As NATO scrambles to beef up its defences in the frontline states and Western diplomacy is humiliated in Syria, the New Cold War is no longer a fanciful book title. It is fact.

As the author of that book — much-criticised when first published in 2008 — I am glad, if alarmed, that my warnings about Russia’s revanchist and repressive policies have been vindicated. Yet one of its central messages has been missed. Russia is not the Soviet Union, and this is not a tussle of strength between global superpowers. We — the European Union, NATO, the West in general—are losing not because we are weak, but because we are weak-willed.

Russia’s weapons include lies, money, espionage and bluff. It deploys them with the decisiveness, even recklessness, that comes from autocratic rule.

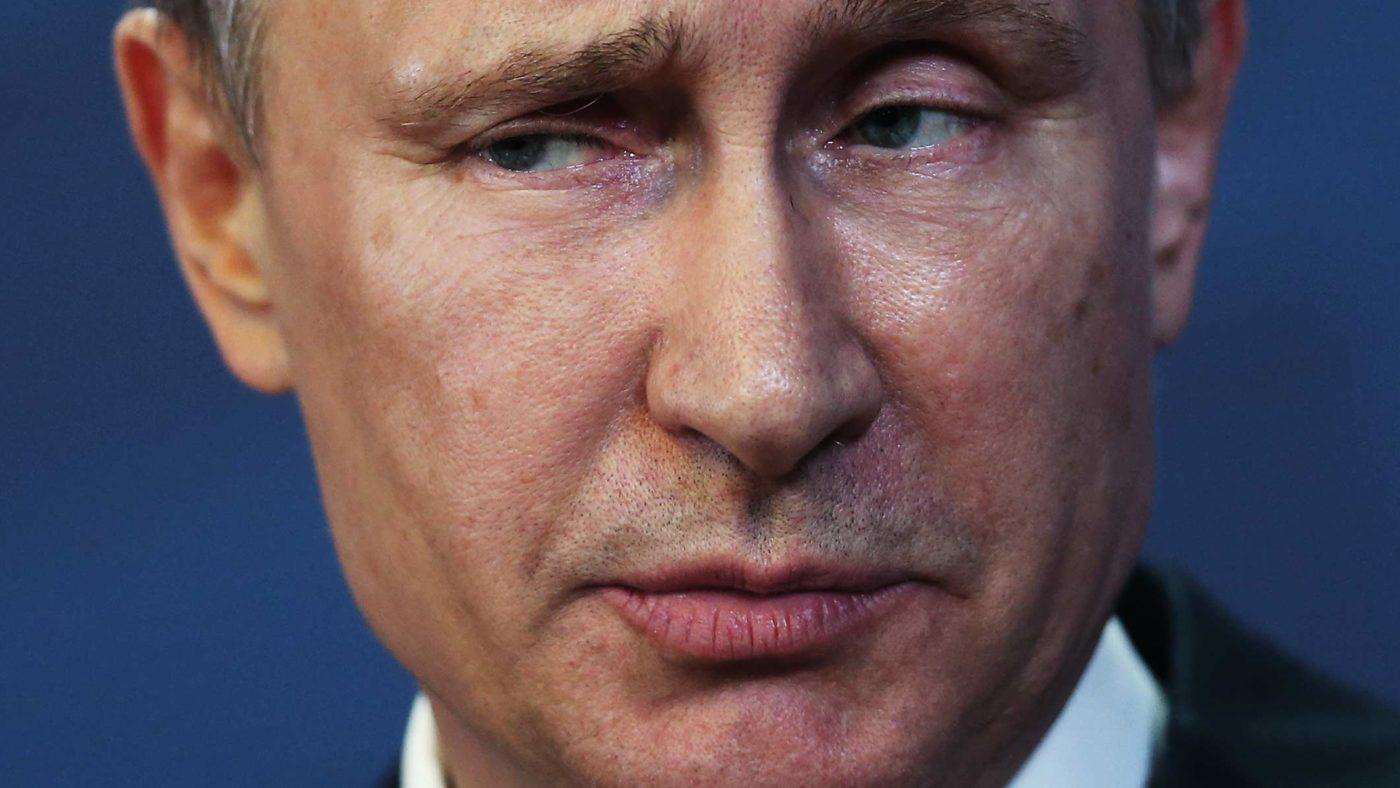

The Kremlin practises joined-up government. Its businesses (especially energy exporters), state agencies (spies and soldiers) and independent public bodies (broadcasters, universities, courts) work together. Ours don’t. Vladimir Putin is willing to accept economic pain; we aren’t. He uses force; we flinch. He threatens the use of nuclear weapons; we find that terrifying.

All too often, we fail to notice even that we are being attacked. We salivate at Russian money, while ignoring its political payload. Even legitimate trade and investment build up constituencies in the West which lobby for the political decisions that will preserve their juicy contracts and deals. That is one reason that our sanctions on Russia since it invaded Ukraine have been so weak.

Worse, Russian money feeds into our public life. Cash-strapped papers regularly carry Russian propaganda in advertorial. The Kremlin overtly bankrolls the National Front in France. Covertly, Kremlin cash supports other extremist, anti-American and disruptive forces elsewhere. We are timid when it comes to tackling these links.

Similarly, we brush off Russian propaganda, believing that our media is invincible and that truth triumphs in the long run. Perhaps, but too much can go wrong in the meantime. Russian media and disinformation outlets stoke conspiracy theories, spread scare stories and corrode our political system with stolen information. Even now, many Americans do not realise that Russia has been trying to get Donald Trump elected, using a pernicious combination of hacking and leaking.

Our media prize fairness over truth. If Western sources say that a Russian missile shot down an airliner over Ukraine, and pro-Kremlin voices dispute this, it is easier to give both sides of the story rather than rule out one side as too tendentious. This addiction to balance is selective. Our editorial decision-makers do not, generally, balance round-earthers with flat-earthers, or astronomers with astrologers. But they are quite happy to host Kremlin viewpoints as though these were entirely legitimate and reasonable.

We can do plenty about this if we wish. It starts with our financial system. The central message of the New Cold War was this: if you believe that only money matters, then you are defenceless when people attack you using money.

The weakest part of the Putin machine: its Western accomplices. Russia can’t launder money on its own. It uses Western—often British—bankers, lawyers and accountants. These are the “guilty men” of our era. They have enabled the theft of tens of billions of pounds every year from the Russian people. They knew what they were doing, and they thought nothing would ever happen to them.

We can change that. We can start with ostracism. Working for dirty Russian clients should be social and professional suicide, akin to dumping toxic waste, trading in endangered species or loan-sharking. We should apply regulatory sanctions, such as professional disqualification: it is a serious breach of the rules, for example, for a lawyer to take on a client whose beneficial ownership is unclear. Only the cost of defending a libel action prevents me giving examples.

Finally there is criminal prosecution. Britain has a lamentable record in prosecuting high-level, white-collar crime, but we could always change that. Moreover, in some cases the money-laundering has an American dimension. The thought of spending several years in a US prison should not only be a powerful deterrent to those still working for Putin and his cronies. It will also be a powerful incentive to turn Queen’s Evidence. With better insight into the Kremlin’s offshore financial empire, we can start rehearsing the ultimate deterrent: freezing and seizing assets.

We don’t need new laws. We just need to enforce our existing ones. British banks have a shameful record on money-laundering, as a report in 2011 by the former Financial Services Authority (now the Financial Conduct Authority) made clear. It highlighted how banks simply ignored the “know-your-customer” requirement for what are called “politically exposed persons” if the profits were big enough. Why worry about the source of the funds when the destination is so lucrative? Lobbying from the City made sure that the recommendations got nowhere.

What we do need is much greater coordination among our different agencies.We need a cabinet committee, chaired by a senior minister, to coordinate our criminal-justice, intelligence, defence, security, financial-supervision and other capabilities.

We can also raise the bar for Russian propaganda. We should lambast the BBC and other broadcasters for their phoney, lazy balancing of truth and falsehood. We should refuse to have dealings with the Kremlin’s lie-machines — the “TV station” RT, and the “news agency” Sputnik.

No reputable commentator, politician or official should lend them credibility by responding to their requests for comment. Let these propagandists stew in their own swamp of cranks and conspiracy theorists. We should encourage Ofcom to continue enforcing its rules on balance in broadcasting — which RT has already tripped over several times.

These counter-measures are far more effective than a military response. It is quite right to bolster NATO’s presence in the frontline states. But we should not fall for Russia’s attempt to frame the argument in its terms: if you defend your allies, you risk a nuclear apocalypse. We are bigger, richer and stronger than Russia. We should act that way.