In the wake of this week’s bombing in Manchester, the nation was united in grief for the victims, and fury at the perpetrators.

Well, almost united. From the dark corners of the internet seeped up a counter-narrative. The bombing was a false flag operation (a “#reichstagfire” affair, to quote the comedian Rufus Hound). Or MI5 allowed it to happen. Or the bombing itself was genuine, but the threat level in its wake was artificially exaggerated. All because Jeremy Corbyn was finally getting through to the British public, and Theresa May and the British Establishment were desperate to stop him.

Such claims were hurtful, hateful and hysterical. Not to mention flagrantly illogical in the claim that a government the conspiracists view as ludicrously incompetent can somehow cajole or coerce dozens if not hundreds of public servants into becoming accessories to murder (an idea lampooned in this classic Mitchell and Webb sketch about the death of Diana).

There has always been a conspiratorial fringe in politics. What’s different now is that conspiracy thinking has gone prime-time. In the US, the Fox host Sean Hannity is busy peddling bizarre stories about the murder of a Democratic aide (and the less said about “Pizzagate”, the better). Donald Trump has invited the “alt-Right” into the White House press corps and merrily regurgitates favourable nonsense about election fraud or the size of the crowds at his inauguration.

In Britain, meanwhile, Jeremy Corbyn – always something of a tinfoil-hatter on foreign policy – professes to be a keen reader of The Canary, the slavishly loyal fan site which brought us such sensationalist bullshit as the HSBC “dark money” scandal, the Sun “smearing” Corbyn over the Manchester attack and, of course, the idea that the PR firm Portland was the nerve centre of an anti-Corbyn coup.

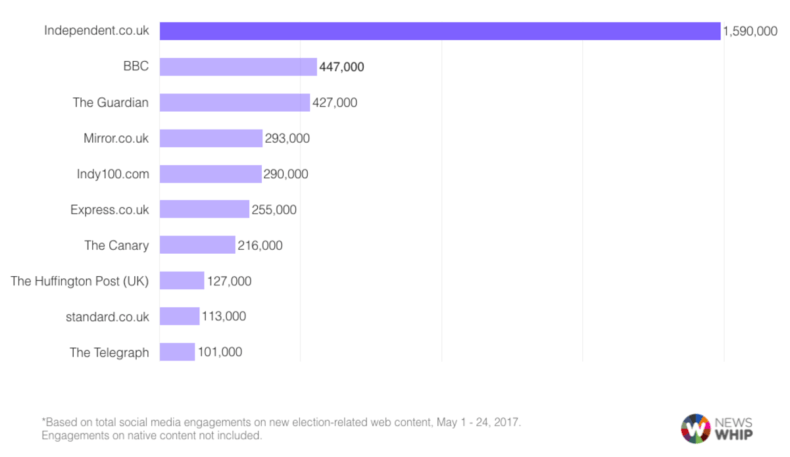

It no longer makes sense, in other words, to talk about a lunatic fringe – it’s now the full haircut. Recently, a firm called NewsWhip looked at which UK sites were getting the most Facebook engagement on their election stories. There was a clear picture of ultra-partisan sites like the Canary (and on the other side the Express) pulling ahead of their more restrained rivals.

Yes, the presence of The Independent at the top of the pile may seem reassuring (and surprising). But much of the political coverage that got it there consisted of clickbait-ish claims that Theresa May had been “destroyed” over the dementia tax or that Corbyn was “finally” getting fair treatment from the biased mainstream media.

There’s a parallel here with politics. The reason that the 2015 general election result came as such a surprise was that the Tories ran a “dark” campaign – precision-targeting individual voters with mailshots and online advertisements that played to the issues they were interested in.

The 2017 election will be even darker: as Rory Sutherland pointed out at the Spectator, someone in Richmond, Yorkshire, will be hearing all about the Tories’ pledge to un-ban foxhunting; someone in Richmond upon Thames may never hear a peep.

In such an environment, the idea of a national manifesto, or a national campaign, slowly withers away, replaced by a strategy of telling millions of voters exactly what they alone most want to hear.

Of course, we have not reached that stage yet. The irony is that the very Corbyn surge which so delighted his acolytes proved the power of the mainstream media and the national narrative: the spectacle of Laura Kuenssberg (often derided, mystifyingly, as a Tory shill) tearing into Theresa May on News at Ten over her social care U-turn must have been worth at least a couple of points in the polls on its own.

And, of course, the reaction to Manchester proved that there are still some events that – for most of us at least – can puncture the filter bubble.

But it’s also worth pointing out that the speed with so many of us are disappearing down our own conspiratorial rabbit holes isn’t an inevitability: it’s been fostered, and hastened, by the internet’s architecture. On Facebook, those liking UKIP get prompted to follow Britain First or the BNP.

On Google, sites like The Canary or Russia Today sit proudly within the Google News corpus, popping up in answer to thousands of search queries – and able, via Google’s AMP instant articles, to appear just as respectable as the BBC or Washington Post.

Over the last few months, the idea that we are in a “post-truth” age has become widely accepted – indeed, there are three separate books with that title (by Evan Davis, James Ball and Matthew d’Ancona) currently fighting for space on the shelves. But it’s more accurate to say we’re in an age when truth is not just relative but personal: known in the heart rather than sifted by the brain.

In the Conservative manifesto, there is a mysterious and tantalising line that promises to “ensure there is a sustainable business model for high-quality media online, to create a level playing field for our media and creative industries”.

But it’s not just about creating a level playing field – it’s about creating a field where we’re all actually playing the same game, rather than a thousand different ones. And, in the process, to stop our politics, and our national life, becoming even more of a dialogue of the deaf and dumb.

This article was taken from CapX’s Weekly Briefing email. Sign up here – or see what you’re missing with the video below.