This weekend, another Budget looms large, the last before we leave the EU. As Brexit consumes Westminster, domestic priorities, such as the burning injustices Theresa May so powerfully articulated when she became Prime Minister, have taken a back seat. This has been to the detriment of families on low incomes, a clear majority of whom backed the vote to Leave. They have been tightening their belts for years and most are yet to see their earnings recover following the financial crash.

But the burning injustice of in-work poverty is one that cannot be left untouched for any longer. Last week a leaked letter revealed 40 Conservative MPs and peers – some of them reportedly ministers – wrote to the Government warning it must restore £2 billion of funding to Universal Credit work allowances. The work allowances operate like a personal tax allowance, the amount families can keep of their earnings before support

to top up low wages begins to be withdrawn.

George Osborne’s decision to cut these allowances in a Budget three years ago has caused a political headache at the worst possible time for his successor, with Universal Credit in the headlines for problems with the roll out. Added to this, the work allowance cuts will only serve to swell the UK’s rising tide of in-work poverty, as analysis for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation shows.

Low wages, high housing costs and the changes to benefits made by Osborne have imposed a major drag on the living standards of people on the lowest incomes, negating policy achievements such as strong employment and the National Living Wage. Now, in-work poverty is rising faster than employment. More and more people are finding that work is not providing a route out of poverty: low pay and scarce progression prospects are becoming the hallmark of the jobs miracle for people stuck at the bottom.

The good news for Phillip Hammond is Monday provides an opportunity to begin to right the wrong of in-work poverty by reforming Universal Credit. If the chatter inside the Commons tearooms and bars isn’t enough to persuade the Treasury, then it should listen to the resounding verdict of people on low incomes and their hopes and expectations for post-Brexit Britain.

Whatever the final deal, the public believes that after March 2019 the government will have more power to shape the country. After nearly a decade of being asked to make hard sacrifices in the wake of the financial crash, working families struggling to make ends meet are impatient for higher living standards and better public services.

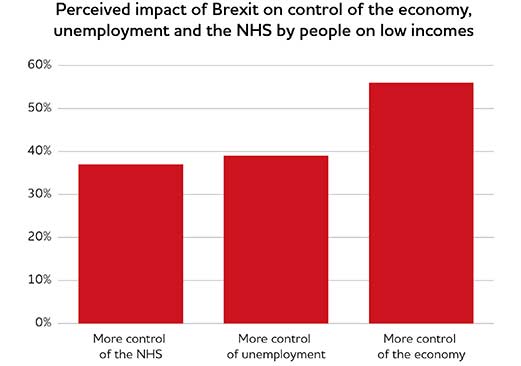

Research we conducted with NatCen showed low income households’ main priorities after Brexit are to improve public services and create more and better jobs. What’s telling is when people are asked about government control over these priorities, a majority believe that government will have more control over the economy (57%), and almost four in 10 think the same about control over unemployment and the NHS.

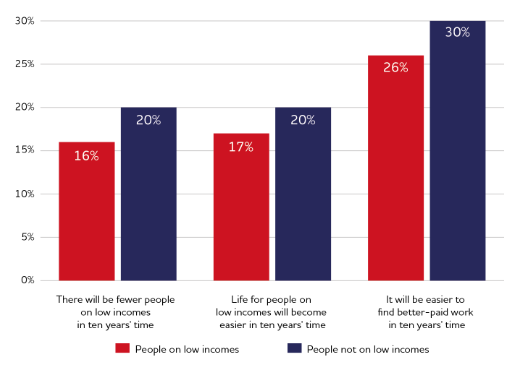

But while people think the Government will have more control, they are not confident it will be used to create an economy that works for everyone. People are relatively pessimistic about the implications of Brexit for the lives of people on low incomes, even when asked to think about the position in ten years’ time. Just over a quarter expect it to be easier to find a better job, while fewer than a fifth believe life will become easier – or there will be fewer people struggling to make ends meet.

This shows the precarious path the Government and anyone hoping to lead it in the future must tread: reconciling people’s high expectations and dealing with their day-to-day concerns. Not to mention doing it at a time when public finances and political tempers are strained. It means Theresa May’s signal at the Conservative Party conference that the end of austerity was in sight must be used wisely. That’s why the Government should use Monday’s Budget to use any additional spending to allow families to keep more of their earnings by increasing the work allowances in Universal Credit.

We all believe work should be the route out of poverty, and that if you work hard, you should be able to make ends meet. But the relentless rise of in-work poverty risks fatally undermining this. As one working mother in Rochdale put it to us in a recent focus group:

“So, the more money you earn from working, the less benefits you get. It’s like taking it out of one pocket to put it in the other pocket and you’re just not benefiting, are you? In the long run, you’re just more tired, you’re not seeing your children as much, you’re more stressed out – and for what, really? Because you’re earning that money and then they’re taking it off you.”

It is hardly surprising people feel dissatisfied and disillusioned with the way the system is designed. Universal Credit should ease the constraints of crippling costs and low wages, and offer a platform from which people can build a better life.

Increasing the work allowances to their original level for families with children would put more money into the pockets of some 4.9 million parents and children in working poverty.

Acting in the Budget would give many a boost to their incomes a week after Brexit, when the new tax years kicks in. It would be a significant first step to delivering the kind of change many voted for. As we leave the EU in March 2019, there remain three years until the next General Election in 2022.

With the public demanding action, three more years of standing still will not do. If we are to deliver a post-Brexit Britain that works for people on low incomes, this means taking steps to tackle in-work poverty in the Budget, not just secure favourable trade terms and return to business as usual. After years of stagnant living standards, low income households will know the end of austerity is in sight when they feel it in their pockets.