In the immediate aftermath of last year’s referendum, I asked a Ukip strategist about the now infamous “Breaking Point” poster which had been unveiled by Nigel Farage an hour and a half before Thomas Mair, a neo-nazi, yelled “Britain first” and murdered his MP, Jo Cox.

Was the poster inflammatory? Did it go too far? The strategist didn’t think so. “If that was level one, we had posters ready to go which were level three,” he told me. Because of Jo Cox’s murder, those posters never saw the light of day.

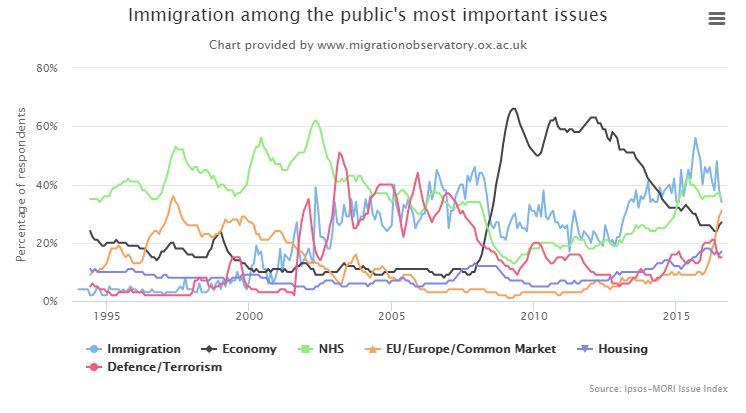

The vulgarity of the poster that was published, and the furore it caused, was proof – if any were needed – that, by 2016, immigration had muscled its way to centre-stage in British politics.

Surprisingly, perhaps, Farage didn’t get into politics because of immigration. In fact, the first mention of the issue on any of his campaign literature was in 2004, 11 years after Ukip was founded and five years after he had first been elected to the European Parliament.

What had shot immigration up the agenda and onto Farage’s radar? In short: the numbers. In 2004 10 new countries were welcomed into to the European Union. Citizens from those countries enjoyed the rights of free movement from day one. Existing member-states could impose interim restrictions on their right to work for up to seven years. The UK chose not to.

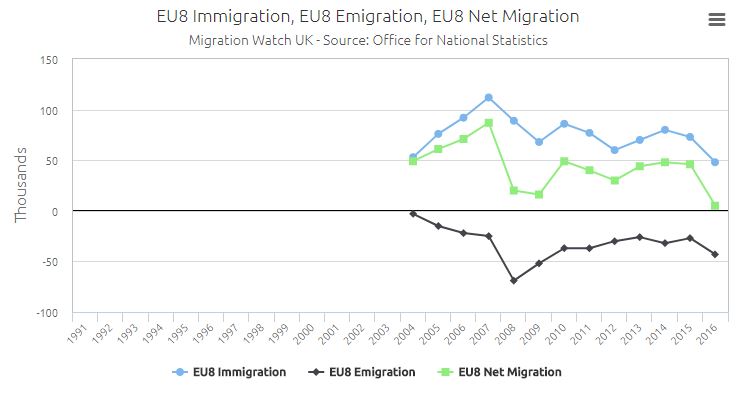

In what must go down as one of the biggest miscalculations in recent British political history, civil service estimates predicted that EU enlargement would mean an increase in immigration of between 5,000 and 13,000 people per year between 2004 and 2010. Those numbers were way out, as this chart showing migration between the UK and the EU8 (the 10 new member-states minus Cyprus and Malta) demonstrates.

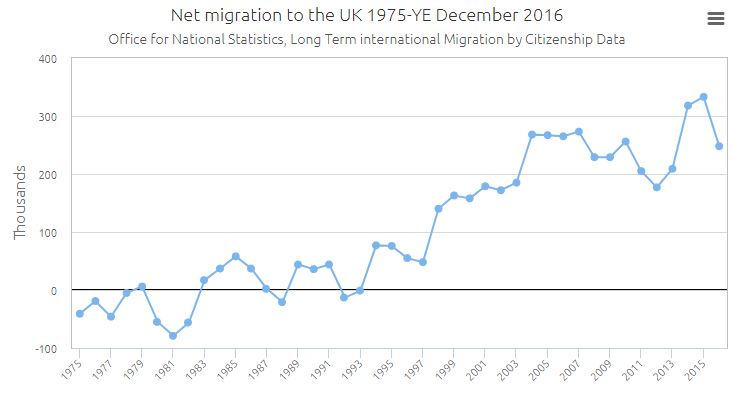

More generally, the last two decades have seen immigration to Britain on an unprecedented scale (see below). During New Labour’s time in government, net migration to Britain quadrupled.

These numbers are why, whatever your stance, any discussion of the issue should start with an acknowledgement of the extent of the demographic change taking place in Britain. Along with the understanding that increased public concern about migration is rational insofar as the issue’s salience has risen, very roughly speaking, in line with the scale of net migration to the UK.

In other words, immigration cannot be dismissed as a non-issue stoked by the right-wing press and fear-mongering populists.

In the 13 years since Farage realised that immigration might be a vote winner, Britain’s debate on the subject has veered from one unhealthy extreme to the other. For most of the Noughties, the national conversation on immigration – an inherently emotional subject – was closed, with liberals adopting what David Goodhart has called a “discrimination presumption”.

That attitude was typified by Gordon Brown when, on the campaign trail in 2010, he was caught on mic dismissing Gillian Duffy, a voter who had expressed concerns over immigration, as “just a sort of bigoted woman”.

Brown’s attitude was, in some respects, understandable. Immigration, and issues of race and identity wrapped up in it, had been talked about in inflammatory terms in the past. Most infamously by Enoch Powell in his Rivers of Blood speech in 1968.

But however justifiable liberal worries about the politics of immigration, the censorious approach adopted in mainstream British politics exacerbated public dissatisfaction with immigration policy. Not least because it meant that the positive case for immigration was not subjected to the proper scrutiny that would keep it robust and persuasive. But then came the over-correction.

The Conservative Party’s 2010 manifesto declared that “immigration today is too high and needs to be reduced. We do not need to attract people to do jobs that could be carried out by British citizens, given the right training and support. So we will take steps to take net migration back to the levels of the 1990s – tens of thousands a year, not hundreds of thousands.”

With the exception of the decision to invade Iraq, no single government policy has done more damage to the standing of politicians in the eyes of the British public than the Conservative migration target, an objective that the party has stuck to – and missed – every year since 2010, generally at the insistence of Theresa May.

This may seem a hyperbolic claim. But, on one of the most important issues facing the country, the government made a promise it knew it could not keep if the UK remained a member of the European Union.

To voters who thought there had been too much immigration into Britain, the existence of the target was confirmation that they were right. And the year-on-year failure to meet the target was confirmation of the government’s ineptitude.

Once the government conceded it had to do something about immigration, but could do nothing about immigration from the EU, it resorted to absurd and offensive tokenism. Stunts such the Home Office driving vans emblazoned with “go home” around London or, after the referendum, Amber Rudd calling for firms to draw up lists of foreign workers lowered the tone of the debate while doing nothing to actually alleviate voters’ immigration worries.

As for the referendum, the debate is still raging over what role immigration played in delivering the Leave vote. Crudely put, the argument is over which of immigration or sovereignty was at the forefront of people’s minds when they opted for Brexit. But this is a false dichotomy. After all, the Leave campaign could not have designed a better illustration of a lack of sovereignty than the government’s inability to determine who comes and goes at the border.

Which is where Brexit comes in. Leaving the EU will be a chastening experience for Britain’s politicians. There will be no Brussels bogeyman to blame when they fail to deliver on various promises. That is truer of immigration than any other policy area.

As long as Britain is in the EU – or the Single Market – debates about immigration are largely phoney. One politician can make the case against large-scale immigration, another can defend it. But translating the outcome of that debate into government policy is simply impossible. Free movement means as many Europeans can come to the UK as want to – no matter what British voters had been promised.

Leaving the EU turns that phoney war into a high stakes battle. Those who see the economic benefits of open borders will have to make their case more vigorously than ever before. They have had it easy until now, safe in the knowledge that for as long as free movement of people remained in place, there were only so many constraints that could be placed on migration. After Brexit, losing the argument will have consequences.

For those on the other side of the debate, their theories can finally be tested. If the downsides of the recent rate of immigration have been so blindingly obvious, then Britain can now experiment with a less liberal system and judge the social and economic consequences for themselves.

Either way, the immigration debate will, from now on, have to be more honest, more meaningful and, therefore, less corrupting of our politics in general. The stakes couldn’t be higher.

The new, healthier politics of immigration starts tomorrow evening with a CapX debate in the Houses of Parliament, the full details of which can be found here.