Has anything changed the world more than the internet? South Korean economist Ha-Joon Chang thinks so. He would argue that one invention – an engine of liberation – has had a far more powerful effect on daily lives. He means the washing machine, of course, which the late Hans Rosling called the greatest invention of the industrial revolution. It freed women from the chore of laundry – or at least from spending one full day a week every week doing it.

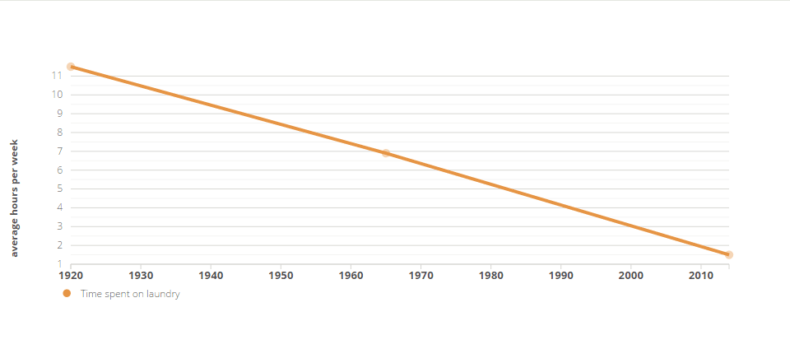

As a result, Americans now lose less than two hours a week to the task, and today a greater proportion of poor US households own washing machines than average American households did back in the 1970s. While washing machines are far from being the only reason that women’s options have multiplied in the West, they have certainly helped. “Without the washing machine,” claims Chang, “the scale of change in the role of women in society and in family dynamics would not have been nearly as dramatic.”

Source: Econweb and BLS

The change is ongoing. Thanks to economic growth and rapidly declining global poverty, more women own or have access to washing machines than ever before. Even so, one 2013 study estimated that, in 2010, 46.9 per cent of households worldwide owned one. That means the market for washing machines has significant room to grow – and that there is a vast amount of latent human potential still out there, yet to be unleashed.

Take China, home to the greatest escape from poverty of all time, when economic liberalisation freed hundreds of millions from penury. The economy (measured in 2014 US dollars and adjusted for differences in purchasing power) grew 31-fold between 1978, when the country abandoned communist economic policies, and 2016.

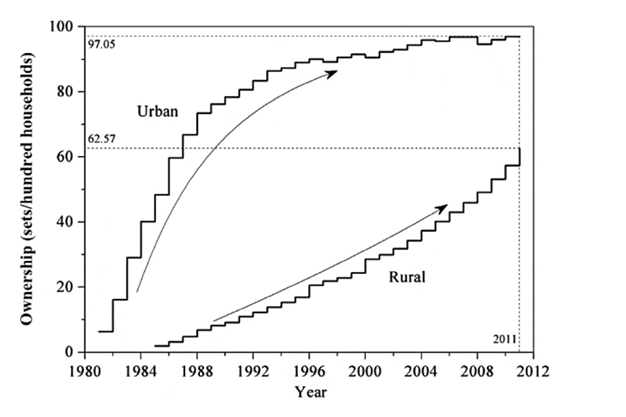

In 1981, less than 10 per cent of urban Chinese households had a washing machine (as approximated by the number of sets per hundred households). But by 2011, 97.05 per cent did. In 1985, less than 5 per cent of rural Chinese households had a washing machine, partly because of the expense, but also because they lacked access to electricity. By 2011, 62.57 per cent owned a machine. Thus possession of a washing machine is a useful indicator, not only of China’s tremendous progress, but of the narrowing gap between rural and urban areas.

Source: Laili Wang, Xuemei Ding, Rui Huang and Xiongying Wu, “Choices and using of washing machines in Chinese households,” International Journal of Consumer Studies (38) 2014, pp. 104-109.

It’s a slightly different story in India, where liberalising economic reforms didn’t begin until 1992, rather later than in China. From 1992 to 2016, India’s economy grew four-fold. Only 11 per cent of Indian households owned a washing machine in 2016.

As with China, urban households are better off, with machine ownership now topping 20 per cent in the most populous cities. That means many women still do the laundry by hand, pounding and scrubbing for hours, in some cases with no running water. Nonetheless, movement is in the right direction. As India’s economy grows and poverty declines, more women will be able to ditch the dirty washing.

We have come a long way since Bendix Home Appliances patented the first automatic washing machine for domestic use in 1937. As a Bendix ad in Life magazine put it in 1950, “washday slavery became obsolete in just 13 years” for American women. In 2007, Panasonic launched laundry machines with a sterilisation mechanism designed specifically to address Chinese consumers’ priorities and successfully increased its market share in the country.

It is important to note what is at the root of this progress. Not only has competition and the profit motive incentivised the washing machine’s invention, it is the capitalist drive that is ensuring ongoing marketing to new customers in developing countries. Innovation stagnates under socialist systems, but capitalism has created more life-transforming innovations than any other economic system and sown the greatest rise in living standards in history.

Africa remains the continent with the worst record on economic freedom, as well as being the poorest continent with the least access to time-saving technologies. But even in Africa, the vicious cycle is breaking and capitalism is slowly helping to alleviate poverty. Washing machine ownership might be low, but most Africans are optimistic about their economic future and possibilities.

Thus today, washing machines are still doing the work they were doing 80 years ago – which isn’t just cleaning clothes. These juddering boxes are life-transforming technologies that allow women to put their time and labour to more constructive use. And as ownership sweeps across the world, we can also track the progress of economic freedom.