In a January 4 article in The Telegraph, Anne Hanley reminisced about her recent trip to Venice. “Venice’s inhabitants were outnumbered by visitors,” she observed. “Around 54,000 under-pressure locals shared their city with just over 62,000 incomers … [and] that, for La Serenissima, is a ‘quiet’ day,” she continued. The city, she concluded, is being “killed” by tourism and will not be saved by new taxes levied on visitors.

As disposable incomes in previously underdeveloped countries increase and transport costs decline, global tourism will continue to expand. Overcrowding in major tourist spots, like Venice, can be unpleasant. I know. I have seen and experienced it firsthand. But, democratisation of travel has an upside. Millions of people are getting the opportunity to see the world for the first time and that is something worth celebrating.

As with so much else in the past, travelling was difficult and often dangerous.

Roads, where they existed, were rutted. Sailing was hazardous. Highwaymen and pirates were ubiquitous. Moreover, a great many people were not free to travel. Serfs and slaves could not journey without their masters’ permission. Similarly, women were discouraged from travelling unaccompanied. Most people could not afford to buy or rent a horse and had to walk long distances. Travel was also limited to daylight hours, meaning the window of opportunity was much smaller, especially in winter. And when on their journey, travellers were often preyed upon by unscrupulous innkeepers.

That said, a small percentage of the population did get to travel – for trade, on pilgrimages, and into war.

Travel for pleasure or out of curiosity is a relatively modern phenomenon. It was popularised, at least in the European context, by wealthy young noblemen who, beginning in the 17th century, started to undertake “The Grand Tour” of European cities, including Paris, Venice, Florence and Rome, to take in the ancient monuments and works of art. These educational rites of passage were expensive and time-consuming. Consequently, they were restricted to rich “gentlemen of leisure.”

The cost and convenience of travel dramatically improved with the advent of the steam engine. In the 19th century, trains enabled unprecedented numbers of people to travel within countries, while steamships sped up international travel. Early steamships cut the sailing time from London to New York from about six weeks to about 15 days. By the middle of the 20th century, ocean liners like the SS United States could make the trip in less than four days. Today, an aeroplane can fly between the two cities in 8 hours. Commercial air travel took off between the world wars, but flying remained expensive for decades to come. In 1955, for example, a one-way ticket from London to New York cost over $2,737 in today’s money. Economy class didn’t exist, so only the very rich got to fly. Today, it is possible to get from New York to London for as little as $200.

The quality of travel has changed as well. In his 1998 book, Isaiah Berlin: A Life, Michael Ignatieff notes that in the spring of 1944, the British philosopher “found himself on an interminable transatlantic flight [from Washington, D.C.] to London. In those days the cabins were not pressurised and travellers had to spend the long hours in the dark, breathing through an oxygen tube. Unable to sleep – for fear that the tube would slip out of his mouth – Isaiah remained awake throughout the night in a dark, cold, droning aircraft, with nothing to else to do but think.” What Berlin lost in discomfort, the world gained in philosophy.

Today, those of us stuck at the back of planes often bemoan the discomfort of long-haul flying. But, compared to mid-20th century air travel, flights today are positively blissful. Unsurprisingly, the numbers of international passengers keep rising.

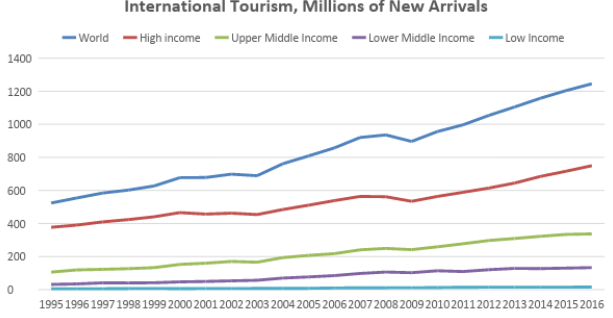

According to The World Tourism Organisation, 524 million people got to travel to a foreign country in 1995. That number grew to 1.245 billion in 2016, a 138 per cent increase. Over the same time period, the share of global travel undertaken by residents of high income countries declined from 72 to 60 per cent. The share of travellers from upper middle income countries rose from 8.5 to 27 per cent. Residents of lower middle income countries increased their share of global travel from 2.5 percent to 11 percent. As in so many areas of modern capitalism, a luxury that was once reserved for a tiny sliver of society is now available to an ever-increasing number of people throughout the world.