The dynamics of the UK’s housing crisis are well-documented: millions prevented from getting on the housing ladder, sky-high rents for often woefully inadequate accommodation and, underpinning it all, a planning system seemingly designed to stop development rather than encourage it (most recently detailed on CapX by Sam Watling today).

Perhaps less well understood is how difficult it has become for younger jobseekers to follow Norman Tebbit’s infamous (and almost always misquoted) injunction to up sticks and find work elsewhere.

Tebbit’s example concerned his Dad getting on his bike to look for work, but the modern British economy often demands youngsters travel a fair bit further to pursue their career dreams in a big city.

Unfortunately, as today’s thorough report from the Resolution Foundation makes clear, housing costs mean that many are shut out of the opportunity to move at all. This isn’t about people being unwilling to make sacrifices, more that it doesn’t make economic sense to move from somewhere with cheap rents and low wages to somewhere that may have higher wages, but has a far higher cost of living too.

It’s not a wholly negative phenomenon. As the report notes, there are more jobs in more deprived parts of the country these days, so the “push” factor of needing to go elsewhere to find work has diminished. The “pull” of more productive areas has also weakened. In 1996 the top decile of local authorities offered an 80 per cent pay premium compared to the bottom decile. That figure has now fallen to 62 per cent.

Looking at specific areas makes this trend especially clear. For instance, if you had moved from Stoke-on-Trent (decile 3) to Croydon (decile 9) back in 1997 you could expect an average earnings boost of 26 per cent after housing costs, today the same move would actually leave you worse off.

The explosion in prices in most of our big cities obviously affects would-be renters, but it is also a big issue for homeowners who might have found their dream job in a different city.

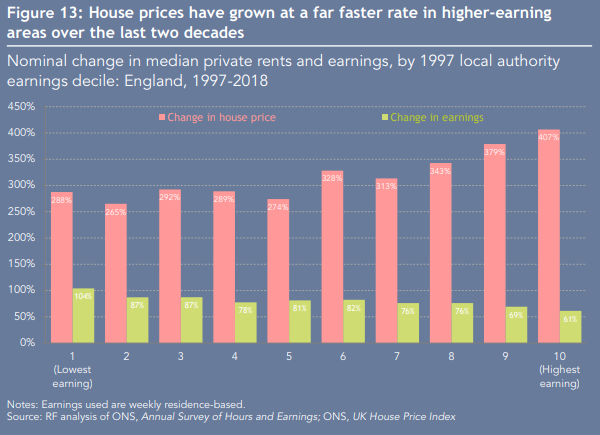

Indeed, this graphic shows that while house prices have risen across the board, they have been most acute in the highest-earning local authorities, while wage growth has been lowest. In absolute terms, people may still be earning considerably more than those in poorer areas, but their purchasing power in the local property market has been steadily eroded.

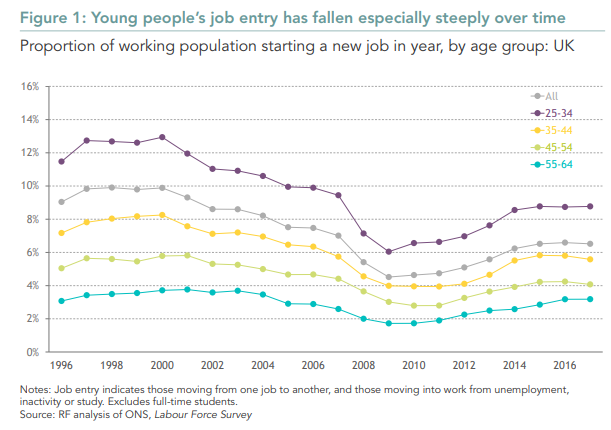

But it’s the findings about younger people that are most startling. For instance, since the turn of the millennium the number of people aged 25-34 moving home to start a new job has fallen by 40 per cent. That certainly gives the lie to the idea that millennials are all footloose multi-jobbers doing their thing in the gig economy.

As the graph below demonstrates, the long-term trend has been for younger workers to stay in a job for longer, although things have picked up a bit in recent years.

That this particularly affects younger people matters because, as author Lindsay Judge points out, “efficiently matching with job opportunities is especially important for young people at the beginning of their working lives”. If they can’t get where they need to be at the start of their careers, younger workers may never get there at all.

That also has profound implications for the overall health of the British economy. After all, if people can’t move easily, businesses can’t get hold of the people they need to develop. As Judge notes, the “vast majority” of job moves in the UK do not involve the worker in question moving house. While in 1996 15 per cent of job moves involved someone moving home too, that figure was only 12 per cent in 2017-18.

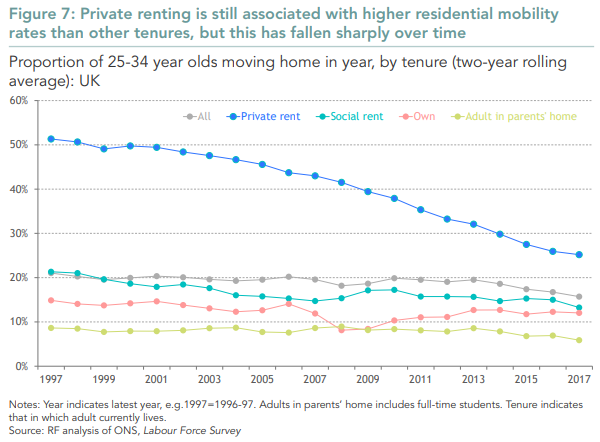

It might not sound like a dramatic statistic, but when one considers that younger workers these days are better educated, less likely to be married and much more likely to be renters — all the things that would ordinarily suggest a high degree of mobility — a clearer picture of the problem emerges. Indeed, the Resolution Foundation calculates that the number of people moving for work should have increased by some 50 per cent over that 20-odd year period, whereas in fact it has fallen by a third.

Again, this trend is very strongly correlated to the high cost of the private rented sector — as this graph starkly illustrates:

While the Resolution Foundation’s work is commendable in terms of the rigour of its analysis, its purpose is not to offer particular solutions. And it would be misleading to suggest there is any single silver bullet for the problem of higher rents and exploding house prices.

Liberalising the planning system in general, and freeing up Green Belt land in particular, are certainly a part of it. We could also do with far less government interference in the market through schemes such as Help to Buy, which have effectively pumped up the demand side of the market with no commensurate increase in supply.

And while building more homes is clearly an integral part of the policy mix, there needs to be just as strong a focus on infrastructure, and not just grandiose projects such as HS2. Large swaths of the UK remain badly connected, with an infrequent bus service at best, while intra-city transport in some urban areas is also woeful. Simply put, better transport links means a wider net for both employers and would-be employees.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.