One of the most unappealing aspects of contemporary British politics is the way in which parties, some more than others, spend their time trying to shame their opponents rather than laying out their own ideas for improving the economy or dealing with an increasingly dangerous international situation. The latest example of this tendency is the witch hunt of Labour candidates who are accepting a donation from the party’s former leader, Tony Blair. He is a triple election winner who was Prime Minister for a decade. Why shouldn’t he give money to help candidates fight the forthcoming general election? Those pious souls shouting “blood money!” (because of Blair’s Iraq War record) should be told, by Labour people, to get stuffed.

That is not to say that the Blair record is perfect. Indeed, his enemies are pursuing him with renewed vigour, using the question of his earnings as a proxy with which to baseball bat his reputation.

While I have always tried to keep a relatively open mind on the man, because there was something unappealing in the late 1990s and early 2000s about the foaming at the mouth intensity of Blair haters, I recognise that he could be intensely annoying. As when he said in the first flush of power that Britain is a young country. No, it’s not. It is a very old country with an ancient history and a growing number of elderly citizens. But he said that, I suspect, because he is ahistorical.

The suggestion that Blair was a Tory was always daft. In office he was a textbook progressive – in the worst sense – in that he was forever looking forward, striving for change in the name of modernity, without realising that in the web and weave of history are useful lessons and warnings about what can happen when a messianic leader takes a casual approach to the constitution or gets into the war business without understanding it.

Yet, there are areas in which Blair deserves great credit. On public sector reform he realised after a few years that competition encourages innovation and drives improvement (welcome to the party, many of us thought, when he had that epiphany). Much of Labour tried to fight him on these reforms to education and healthcare, but he bravely persisted and did valuable work. The battle that had been begun by Tory ministers in the 1980s was stepped up by Blair and then continued by Michael Gove. These reformers asked a good question and came up with an answer. Must a high quality schooling be the preserve of those who can afford to buy it for their children or move to an area with better schools? No. Competition, choice and a rigorous concentration on standards are the way to extend opportunity.

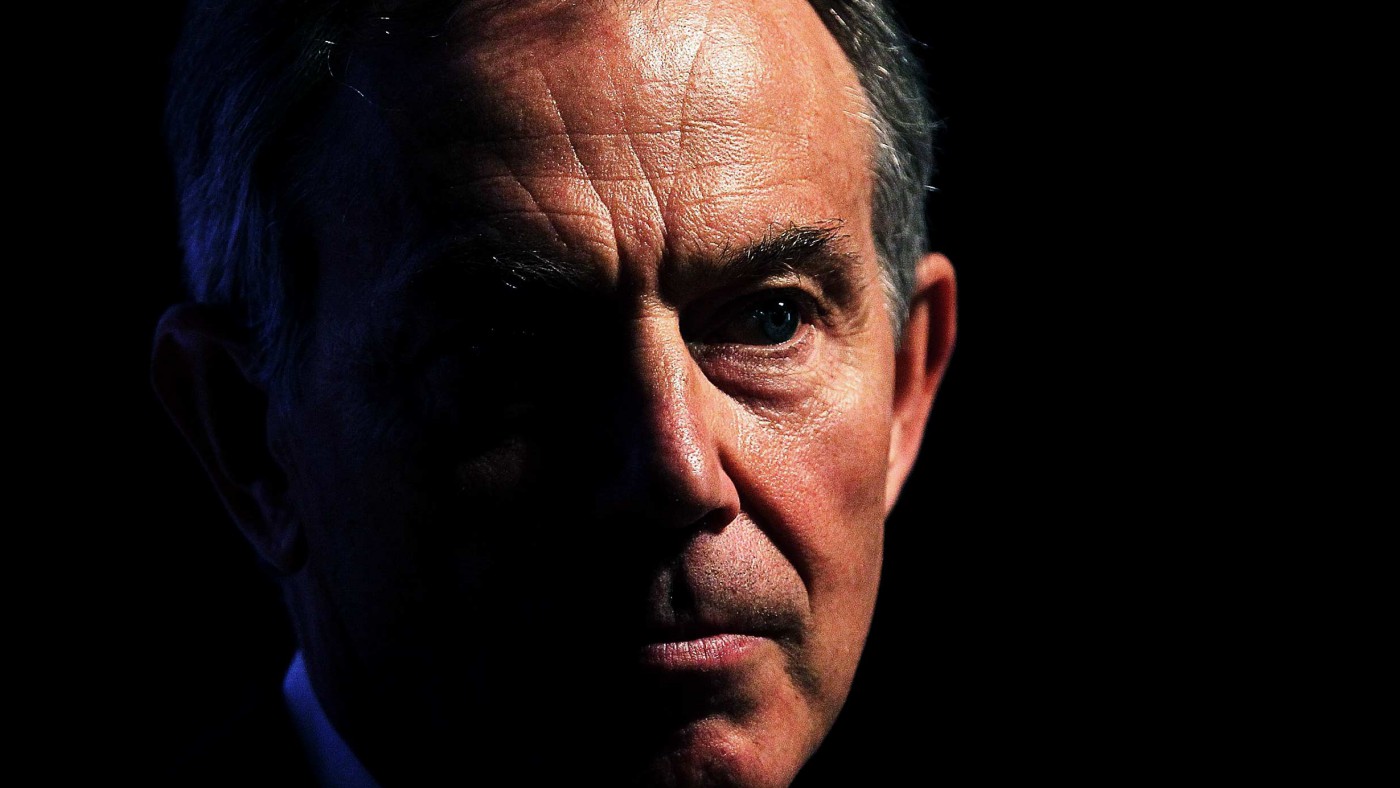

But that’s where, on the positive side of the ledger, I run out of reasons to defend Blair. Indeed, as he passes into history, the record looks worse by the year. I am not referring to the decision to take part in the Iraq War, which as an armchair general I was in favour of (other people) fighting. That is a subject for another time and another place. What is most striking is the Blair failure in four of the spheres that one might consider most fundamental in terms of a Prime Minister’s responsibility. Not all of these failures were directly his fault. There were deep forces at work. But Blair gets his picture on the wall; he was the Prime Minister. Some of the blame falls at his feet.

1) The constitution. Blair’s ahistorical attitude to the UK’s unwritten constitution can be summed up by his almost comical attempts, on a whim at speed, to effectively abolish the office of Lord Chancellor. He obviously did not realise that he was like a little boy pulling at a single thread. Keep pulling and the garment, which took centuries to knit, unravels. But that was a minor matter compared to the havoc unleashed by his asymmetrical devolution of power to Scotland and Wales, which left England without matching arrangements. Tam Dalyell warned that this would create resentment and put Scotland on a motorway to independence with no exits. Less than twenty years later, the UK is speeding towards breakup.

2) The economy. In theory, it was mainly Gordon Brown’s fault that the UK became hopelessly addicted to private sector debt and booming banks that grew dangerously to 450% of UK GDP. To make matters worse, policy (spending, regulation) was predicated on this mad boom going on for ever, which history shows it never does. But Blair let Brown do it. The result was Britain being very badly exposed going into a global crash and a slump.

3) Britain emerged from the end of the Cold War with its international reputation in good shape. Our intelligence and security capability was widely admired and our armed forces had, against considerable odds, retaken the Falklands in 1982. The Tory defence cuts that followed the fall of Communism went too deep (which was hardly Blair’s fault) but on arriving in office Blair fell for war as an instrument of policy without realising there were limitations to our capabilities. There is no evidence from his record before 1997 that he had given war any thought, or read much about it, or discussed it with strategists, or done anything to make up for the fact that he is, like most of us now, lacking first hand experience of war. Instead, he plunged into it. Even after 9/11, when he responded magnificently to America in distress, the warnings of trouble were there. He said that the US had stood with Britain in our hour of peril in May 1940. No, not really. America entered the war quite a bit later; that is the point. In the summer of 1940 we were alone apart from the distant Empire and American journalists in London trying to wake up their fellow countrymen. Then, at the critical moment on Iraq Blair did not bang the table, as Thatcher would have done, and demanded to know what the plan for the aftermath was. He said nothing, and look what happened next. The cumulative result? Consider Britain’s timidity and the state of our armed forces now as the international situation deteriorates. Could we even fight Belgium if it decided to invade Britain? I doubt it

4) Controlling the nation’s borders. Even if one is enthusiastic about a small country such as Britain adding millions of people per decade to its population, in the most crowded parts of the country, it surely would have been helpful if the Prime Minister of the day, when a migration surge began, had given some thought to how it might be managed sensibly. Instead, Blair and his colleagues rubbished anyone who expressed even mild concerns about the impact or sought to limit the numbers. In place of a grown-up discussion about border control (a primary responsibility of government) the critics were smeared as racists. Now, the Office of National Statistics estimates that by 2035 the UK’s population will hit 73.2m, an increase of almost nine million on today. Where, in terms of houses I mean, are they all going to live?

There it is. And it is quite staggering. Those are the basics of being a national leader. On safeguarding the constitution, running the economy sensibly, defending the realm and managing immigration, Blair was not very good. Which is very bad in a Prime Minister.