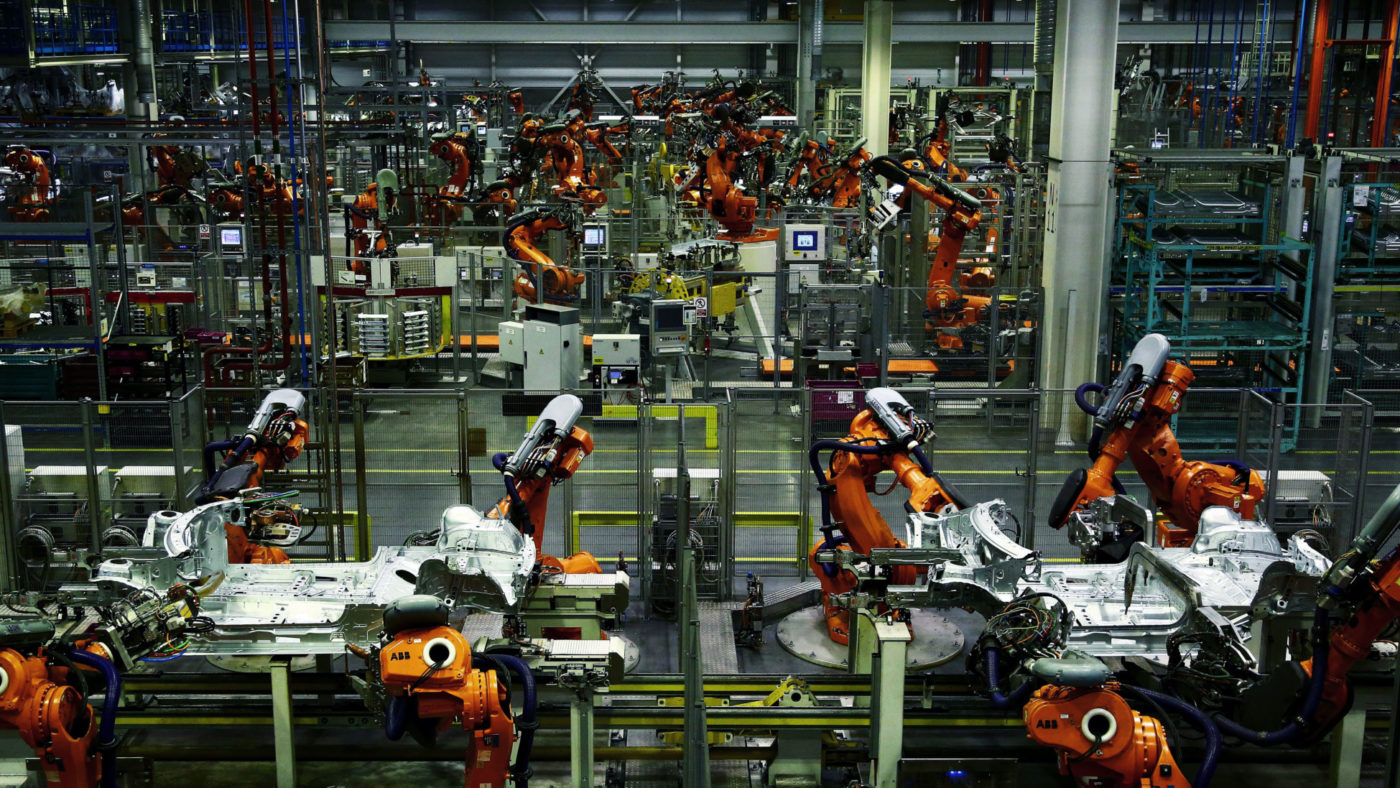

There is an alarmist belief that western economies are careering towards an era of mass unemployment as robots, AI and Fourth Industrial Revolution technology replaces workers. Dr Carl Frey and Professor Michael Osborne from Oxford University used an algorithm to predict the computerisation of different roles within an economy and forecasted that almost half of all jobs in America could be automated.

The ramifications of this would be huge. It would hit the low-wage economy hardest and undermine the lives of those least able to bare it; we’d need a far-reaching state funded universal income to sustain an acceptable quality of life for the new structurally unemployed population, as well as a tax system that captures economic value generated by robot workers.

These predictions are somewhat dystopian, with each generation consistently unable to enjoy the fruits of economic progression while the joys of working and a career are isolated among a cadre of bureaucrats and financiers. And while it is true that technology will change the way we work and the millennial generation face barriers to economic wellbeing that their parents avoided, the future of work should not be seen as nightmarish.

The next generation can be richer than the last, provided we get the policies right.

The Centre for Social Justice was founded on the principle of work being the best route out of poverty and the foundation of a functioning economy. Someone out of work is four times more likely to be poor and a child growing up in a workless household is twice as likely to fail at every stage of education. We should never accept unemployment as a de facto way of life.

In February of this year we launched our 12-month long Future of Work programme. Its mission will be to answer some of the biggest questions facing politicians today regarding what the future of work holds for us all, but in particular what it will mean for those on the edges of work. While many organisations have sought to answer this question, we will focus on our poorest areas and bring with it our experience of working with the charitable sector in some of Britain’s most disadvantaged communities.

We take it as a given that technology will continue to impact not just the number of jobs but also the quality of jobs in our economy. Whilst it is true that certain jobs will be lost to further mechanisation and automation, technology can a job creator as much as a job destroyer.

It is therefore important that our students and young people are equipped with skills and competencies to complement technology and meet the demands of a modern economy. We must examine the curriculum taught in schools, the availability of level 4 and 5 qualifications at Further Education colleges, as well as options for mid-career professionals to access new skills.

To keep employment rates high, we must look at how the British economy can create more high value well paid jobs. That means attracting investment to Britain, developing innovative technologies and ensuring businesses can start-up and grow here.

Britain has one of the lowest capital investment rates in the OECD, investing less as a proportion of GDP than Germany, Sweden or the Netherlands in things like technology or machinery. How can we support the next Google or Amazon to be British born and based?

Lastly, we must address the regional imbalance in job growth and productivity across Britain. Workers in Yorkshire earn 74p for every £1 earned in London, students in the North East were five percentage points less likely than someone in the South East to reach basic attainment in Maths and English GCSE, and London receives 17 times the spending on infrastructure as the East Midlands.

The most recent Social Mobility Commission report pointed out that there is a “stark social mobility postcode lottery exists in Britain today where the chances of someone from a disadvantaged background succeeding in life is bound to where they live”.

The future of the British economy need not be one where each generation is poorer than the last as robots slowly take-over the means of production. Previous predictions by John Maynard Keynes that the future would be a life of idle leisure have proven false. As Nick Boles MP stated, human beings are hard wired for work. It’s only if we address the tough questions that technology, the gig-economy, and globalisation pose, will we be able to make sure the future will be better than the past, for everyone.