From the beginning of Britain’s Covid crisis, comparisons with the Second World War have been inescapable. The profound changes to our way of life, the economic toll and the sense of a shared national struggle have all felt particularly resonant in a country whose national identity has been so profoundly shaped by that conflict.

From an economic point of view, the parallels are especially apt. Just as then, untold economic damage has been met with enormous government intervention. Much of the economy, especially the private sector, had to shut down for several months, and will operate below capacity for a significant period.

And just as in the post-war period, there are plenty of calls now for a permanently larger, more interventionist state. Labour leader Keir Starmer’s speech last week, with its talk of a “1945 moment” was a fine example of the genre.

Much of that argument rests on a carefully cultivated mythology about post-war Britain, particularly on the part of Labour politicians. In this telling, it was only from the rubble of the Second World War that in founding the welfare state and the NHS Britain finally embraced fairness, equality and a brighter future.

But, as I show in a report today for the Centre for Policy Studies, this statist approach also left Britain with a stagnating economy, weak productivity and lower living standards than many of our allies.

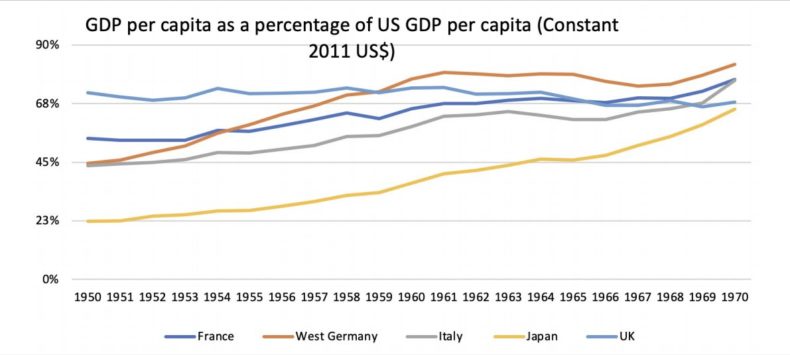

If anything, the lesson from post-war Western economies is that liberalisation was the key ingredient for prosperity. And while Britain’s socialised, sclerotic economy laboured, the likes of America, Japan and West Germany powered ahead thanks to sustained private sector growth.

A US wartime boom?

It’s worth turning first to the US, where the usual revisionist theory goes that it was the war, rather than FDR’s faltering New Deal, that dragged America out of the Great Depression and laid the foundations for post-war prosperity. On the surface the case looks convincing: output figures and GDP data certainly show a wartime boom – followed by a sharp contraction, with high inflation and output falling by over 20% in 1946.

However, as the economist Robert Higgs has shown, these figures are simply wrong – distorted by price controls and central planning which inflated the GDP figure and postponed inflation during the war. When the figures are properly adjusted, one finds that growth was actually poor during the war and then surged once peace was declared in 1945.

Indeed, it was not until after WW2 that prosperity truly returned, as the US ditched central planning and returned to a more free-market system. Spending fell by 75% between 1944 and 1947, from 55% of GNP down to just 16%. By 1947 price and production controls had also ended, as had rationing, and factories had gone back to producing consumer goods rather than the tools of war.

These developments confounded the many economists – particularly Keynesians – who had assumed that without continued government intervention America would fall into a post-war depression. But despite there being over 20 million people, whose jobs disappeared –either via being demobbed or working in war industries – the new depression many feared failed to materialise. In total, around a third of the US labour force was effectively re-mobilised in the service of consumers, a pretty remarkable achievement in itself.

A great many explanations have been reached for to explain America’s low post-war unemployment: the GI bill putting veterans into college and off the jobless rolls; women who had worked in wartime industries leaving the labour force; a consumer boom from ‘forced savings’ as people had few consumer goods during the war years. However, as I show in my report, none of these accords with the economic data. The real explanation is much simpler: a boom spurred by consumer spending and private investment, aided by the government taking a step back.

The UK – the sick man of Europe

What a contrast between America’s experience and that of post-war Britain. Indeed, for all the mythologising of the Attlee government, the UK’s post-war growth actually lagged behind most other countries. Granted, this was partly the result of long-standing structural issues, particularly poor industrial relations. Britain was always unlikely to see the explosive growth of West Germany or Japan in the same period.

However, successive British governments did little to confront those shortcomings, and in many ways exacerbated them.

In particular, although the UK balanced the budget and reduced the vast national debt that had been run up during the war, the expansion of the state acted as a drag on growth. While countries such as the US and West Germany abolished most wartime controls and reduced state intervention, the UK largely maintained and in certain areas extended it, with sweeping nationalisation and continuing food rationing until 1954. These policies created systemic issues which contributed to weak productivity and, with it, low GDP growth, as we can see in the chart below.

.

.

A narrow tax base, high marginal rates and the focus on direct rather than indirect taxation, was another significant impediment. Unlike West Germany and Japan, which both pushed to increase competition and drive domestic firms to be more productive, British policy too often ended up subsidising failure.

This lack of competition in the British economy has been identified as being perhaps the key explanation for why British economic performance was so poor up until the Thatcherite reforms of the 1980s, after which the UK outperformed countries such as West Germany, France, and Italy. For example, Britain’s postwar trade policy was designed to protect domestic firms rather than exposing them to the discipline of international competition.

What of the claims that Europe, and especially West Germany, only succeeded because of the billions of dollars provided by the Marshall Plan? Certainly the extra billions from the US were helpful, but it was the stringent conditions attached to the aid that really made the difference. By pushing countries to embrace market economics, the US sowed the seeds for a period of phenomenal growth in both Europe and Japan.

What now?

What does all this mean for the UK’s post-pandemic policies?

Though you can’t move for pundits and politicians demanding more public spending, the big lesson of the postwar recoveries is that with robust consumer and investor confidence there is negligible need for government stimulus. History, not abstract theory, shows that the best way to boost growth after a ‘wartime’ period such as the pandemic is for the state to take a step back.

This is particularly true with unemployment, which is undoubtedly a top priority, given the millions who have been furloughed or laid off in the last year. There will be countless calls for schemes and subsidies to support various groups. But we should take our cue here from post-war America, where household spending and private investment were the key ingredients for getting people back into work. Ministers should also be hard-headed about withdrawing support from companies which are no longer viable, especially once restrictions are removed.

Overall, the lesson of the postwar recoveries is a simple one: with robust consumer and investor confidence, there is negligible need for government stimulus. The best way to repair the damage is not through schemes, subsidies and special treatment, but by getting out of the way and giving markets the flexibility they need.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.