A little over a year ago, En Marche! didn’t exist – and many French people didn’t know who Emmanuel Macron was.

Now, he is President.

But was his extraordinary victory merely a reaction to the National Front – similar to the rallying round the centre we saw when Jacques Chirac faced Marine Le Pen’s father, Jean Marie, in 2002. Will Macron be able to form a functioning government? And if he stumbles, will it set the stage for a National Front triumph come 2022?

These questions can be partly answered by a perusal of polling data.

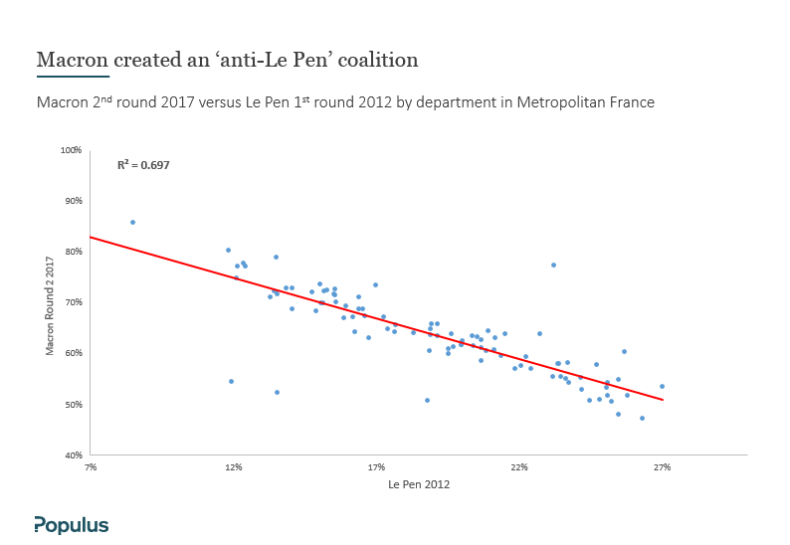

Macron, we find, did indeed create an “anti-Le Pen” coalition. As this chart shows, the more likely you were to vote for Le Pen in 2012, the less likely you were to vote for Macron in 2017, and vice versa.

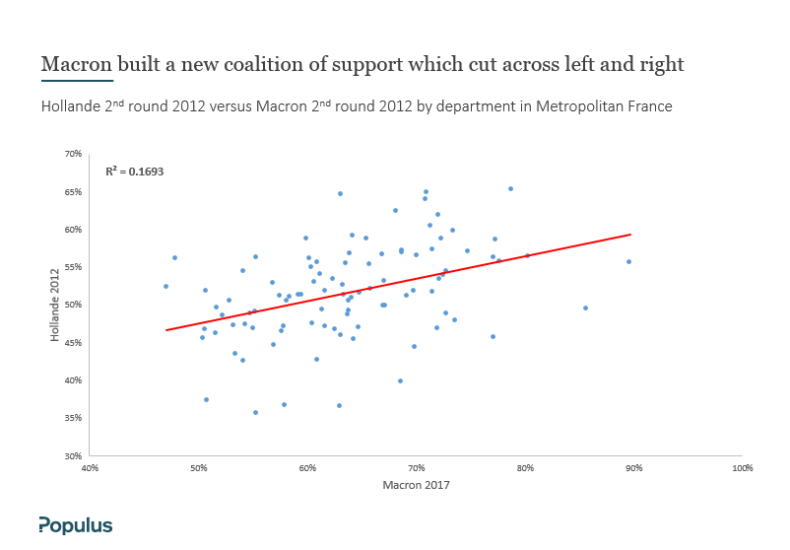

But what’s more interesting is the nature of that anti-Le Pen coalition. Macron did not simply rely on those who voted for François Hollande or Nicolas Sarkozy in 2012: he really did build a new coalition.

Here, for example, is the relationship between Macron’s 2017 second round results and Hollande’s. There is a correlation there, but as the scattered dots suggest, it’s an incredibly weak one (that figure in the top left represents its strength: 1 is a perfect correlation, 0 is no correlation at all). The same is true when it comes to Sarkozy’s voters.

Macron actually brought together a broad coalition of support, drawing in voters who had previously voted for Hollande and Benoît Hamon (Socialists), Jean-Luc Mélenchon (Left Front), François Bayrou (centrist Democratic Movement) and Eva Joly (Green).

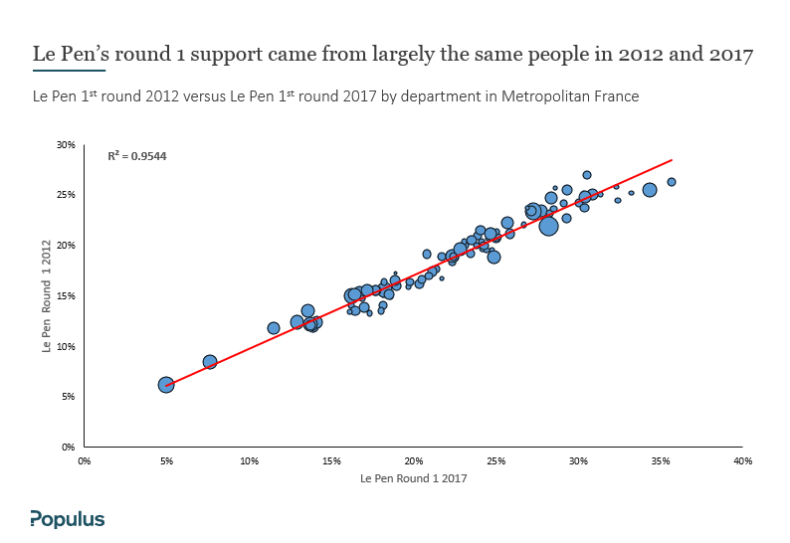

Le Pen, by contrast, relied pretty much on the voters who supported her in 2012. Equally importantly, her greater support in the second round mostly came from piling up votes among the areas and demographics and areas that were already strongly behind her.

This is important not just for France’s future, but for its immediate present.

On June 11 and 18, the French go to the polls to elect their parliamentarians in a two-round system.

Our analysis from the first and second round of the presidential contest suggests that the National Front stands the best chance of winning seats in Le Pen’s heartlands: the north east and the south east of France.

The number of seats the FN actually wins will be partially determined by turnout, and by how many “triangulaires” (three-person run-offs) occur in the second round.

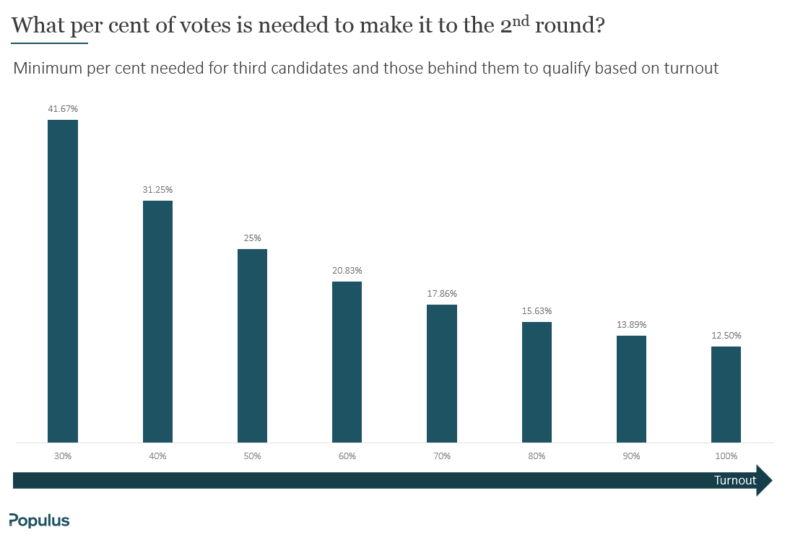

In France, a candidate wins the seat after the first round if they win over 50 per cent of the vote. The top two automatically make it through to round two, but so does any candidate who won at least 12.5 per cent of registered voters that turned out.

This means that the higher the turnout, the lower the threshold, and thus the higher the likelihood of three-way run-offs.

These can potentially be to the benefit of the National Front – the party’s voters are loyal and mobilised, as I discussed with my colleague James Kanagasooriam in an analysis of the French polls for the Legatum Institute. By contrast, the anti-Le Pen coalition will be split between the Republicans, the Socialists and En Marche! (now renamed La République En Marche! or LREM!).

Yet this situation could also help LREM! There is a good chance that Socialist and Republican candidates might pull out where Macron’s party is ahead. It is certainly likely that this will be the Socialist party’s policy, though the situation is slightly more ambiguous for the Republicans.

François Baroin, who is leading the Republican campaign, has taken a tough stance, emphasising the party’s aim to win a parliamentary majority. Yet the moderate wing of the party, including former presidential hopefuls Alain Juppé and Bruno Le Maire, has already signalled that it is willing to put the national interest first, and work with Macron to give France the reforms it needs.

It is, therefore, difficult to know how likely it will be that LREM! wins a majority, but Macron certainly has a chance of it. In almost all legislative elections, the French have rallied behind the party of the presidential winner. And a law passed by President Hollande preventing politicians from holding multiple positions at once means that the other parties will also have many new faces running, lessening LREM!’s disadvantage.

Many, of course, think that the National Front isn’t actually bothered about the parliamentary elections, and is more concerned with laying the groundwork for 2022.

But our analysis suggests that something significant will need to change in order for it to broaden its coalition of voters. Right now, it has a ceiling of support, heavily concentrated in certain demographics (less educated, working class, rural – as detailed here), largely in the north-east and south-east of France. But piling up votes in those areas does it little good in the long run.

Le Pen has already hinted that she will change the party’s name to create a broader “patriotic alliance”. Breaking with its controversial past may be one way of attracting new voters. On the other hand, some party figures are saying that the real name that needs to change is “Le Pen”.

Perhaps the over-arching question – beyond how many seats Macron wins in the legislative elections, and the extent to which he is able to fulfil his programme – is whether France’s politics have changed for good.

Will the centre-Right and centre-Left return as the main political actors? Or will the divide between open and closed replace Left and Right, as seems to be happening in Britain? If so, it could solidify En Marche!’s place in French politics – but also cement the National Front’s position in the political mainstream.