Last week’s publication of the Bacon Review into self and custom-build housing was an important moment in the battle to create a sensible planning system. Although self and custom build are currently only a small part of the UK housebuilding sector, that’s precisely why reform could unlock huge benefits.

Chances are if you mention self and custom-build to anyone from the UK, if they know what it is, they will immediately reply with ‘Grand Designs!’. Although as a TV show it is fantastic entertainment (despite – or perhaps especially? – when things go wrong), it also creates the impression that these new homes are an eccentric, risky choice. But self-build is not just people having a punt on their own. It also includes buyers who simply pick features out of a catalogue and let the professionals build their home for them on an empty plot.

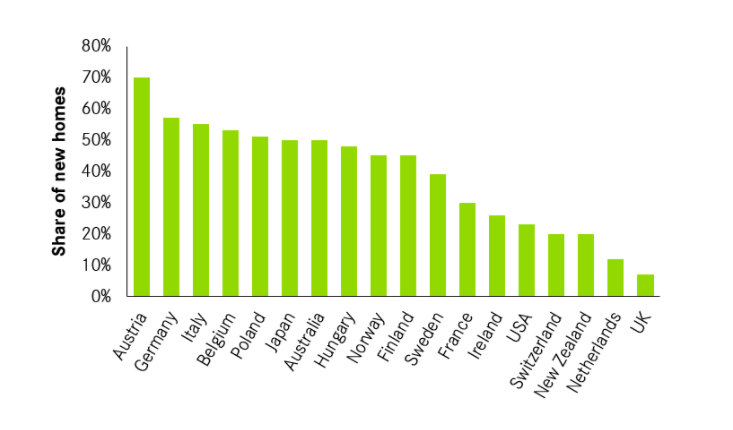

What is undeniable is that the UK has very low levels of self and custom-built housing, even though they are common in the rest of the world. Figure 1 shows that only 7% of new homes self-built or self-commissioned in the UK, compared to around 50% in Australia and Japan, and up to 70% in world-leading Austria.

Figure 1: Self and custom-build homes are unusually low in the UK

Source: The National Custom and Self Build Association, 2020

.

Why are these homes which are so typical in the rest of the world so rare in Britain, especially when we have such a terrible housing shortage?

The Bacon Review looked at exactly this problem, and came to a firm conclusion – Britain’s unusually dysfunctional planning system is why we have such unusually low rates of self and custom-build. To quote the review’s authors:

“Permissioned land is without doubt the single greatest constraint to the growth of the self commissioned housing market… It is hard to understate the challenge presented by the lack of access to development land, and the impact that it has on the supply of homes. It is not just the absence of land but the challenge of finding land and taking it through the planning process, from application, (appeal) and approval. This process involves time, money, and an appetite for risk. It is a process that many simply elect not to take and the housing supply that exists now is primarily the market response to the challenges of access to land.”

This is strong language, as is its comparison to Soviet-style shortage economies, which Centre for Cities has also previously made, but it is worth going into more detail.

Self-build is uncommon in the UK due to the unnecessary risk the current planning system injects into the development process. The current English planning system is highly discretionary, which means that despite the existence of local plans, almost everything is decided case-by-case. Proposals to build that attempt to comply with the local plan can still be rejected.

This is why a raft of recent policy initiatives designed to increase self and custom-build have had only limited impact. Local authorities still decide how to use land in unpredictable and arbitrary ways, as the underlying planning process for rationing land is unchanged. Somebody who buys a plot of land in the hope of getting planning permission still does not know whether they will be successful.

The paradox of the planning system is that its case-by-case decision-making does not encourage bespoke or custom designs. Indeed, the barriers erected it puts in place mean that self and custom-build homes currently require lots of effort from planners on each individual home. And, due to the low number of applications, councils can deny planning permission with few consequences for their housing targets. In other words, England’s case-by-case planning system ends up rejecting custom homes, case-by-case.

In practice, policymakers and the market must instead depend on the biggest housebuilders with the scale to deliver hundreds or thousands of homes on large sites. Building lots of homes in this way requires the minimum amount of effort per dwelling to navigate the complexity of the system and is attractive to local authorities who are anxious to just barely meet their housing targets while rationing land. But it provides little choice to consumers, and means that the largest developers face little pressure from smaller competitors who both cannot work on such large sites and struggle to get planning permission for smaller jobs.

Those who want more competition, choice, and self and custom-build in the housing market should therefore support the Government’s upcoming planning reforms. Potential self-builders and house-buyers more broadly need a planning framework where builders know that they can build so long as they follow the rules. This would increase certainty and provide the space for the housing market to provider greater customisation and choice, even for those who are buying second-hand homes or from the biggest builders.

The upcoming Planning Bill is the best opportunity in decades to achieve this, thanks to the ambitious outline provided in last year’s Planning White Paper. Opponents of reform sometimes attack these proposals as a ‘developer’s charter’, but that could not be further from the truth. In fact, the existing planning system that they defend is the real developer’s charter, as it protects the biggest housebuilders in the country from competition from small and self-builders. The low rate of self and custom-build present indicates there are currently massive barriers, but that also if these are removed that there is plenty of room for growth and higher total housing supply.

The Planning Bill is still being written, and may yet change from the outline of the White Paper. Yet the success of these planning reforms can be judged not just by whether housing supply increases, but by the role played by self and custom-build in doing so. If reform can bring ‘Grand Designs’ within reach of millions more people, housing will become more affordable for everyone – a prize worth winning, even if the TV show becomes a little less disaster-prone.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.