One of the many fatalistic narratives about the Western world is that we are destined to slide into a fiscal nightmare — a society dominated by old fogeys with their feet up, and with fewer and fewer young people to support them. That’s if we survive the impending army of job-destroying robots, of course.

We tend towards a cheerier view of the world here at CapX, so it’s refreshing to see today’s report from the International Longevity Centre, which suggests increased life expectancy is generally a good thing for the economy.

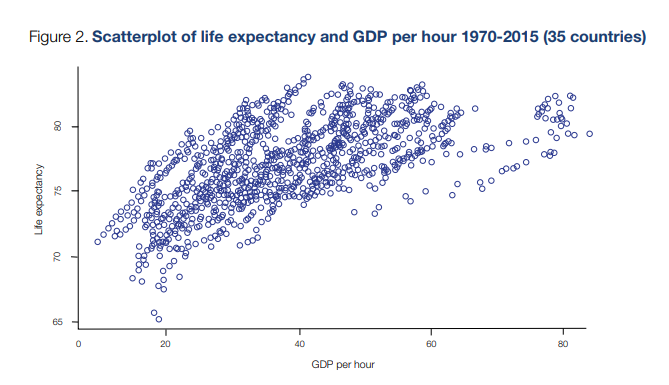

The researchers looked at 35 years’ worth of OECD data across the developed world to try to deconstruct the complicated relationship between longevity and productivity. And its conclusions are arresting:

Based on our analysis of OECD data we find life expectancy is positively associated with productivity. As life expectancy rises, this leads to increased output per hour worked, per worker and per capita.

There’s an important distinction here. What the ILC research suggests is that productivity improves as a result of better health and longevity, rather than longevity simply rising because of a thriving economy. The most obvious corollary of that is that more investment in health may reap an economic dividend.

It’s an important rejoinder to the idea that longer lives is nothing but a drag on developed countries, with the state shelling out ever more for social care and medical payments.

According to the report, there may be a dividend from us all living longer.

As its author Ben Franklin notes:

Many debates about long run government spending, health spending is simply seen as a drain on fiscal resources, yet if by raising life expectancy it results in productivity improvements, this could support increased tax revenue for the exchequer.

Public policy and economic forecasters should consider how best to take into account the potential fiscal benefit of better health and not neglect it in discussions of our long run sustainability

It also another reason to be alert to news that growth in UK life expectancy seems to have tailed off (though claims of a “post-Soviet” crisis sound a bit over-dramatic).

There are several other interesting angles to explore here. One is the role of automation – rather than “taking our jobs”, new technologies could enable older people to carry on working in some capacity later in life, not to mention living more independently at home, with lower resulting care costs.

The shape of education and career paths will also necessarily be different in an era of mass longevity. There’s much less rush to start work at 21 if you can expect to be in a job until well into your 70s. Equally, if we are to work longer, there is a powerful argument for a more relaxed pace to working life.

And though ever-increasing retirement ages are met with howls of disapproval, they are a necessary correction to an anachronistic system.

During the 1970s and 1980s a number of countries had default retirement ages in place, the age range 60-65 become the norm for pensionable age and some workers had the advantage of participating in defined benefit pension schemes. All of these developments created incentives to leave the workforce around the age of 60, irrespective of the health of individuals. It was only in the late 1990s and early 2000s with concerns brewing about the fiscal impact of an ageing population, that governments began dismantling institutional arrangements incentivising early retirements and some started to legislate for older pensionable ages.

None of this is intended to dismiss the fact that many will suffer poor health or find themselves incapable of working as they get older. But it is to suggest that, contrary to some doomsday scenarios, an older workforce need not be a bad thing.