Regardless of the actual fiscal impact, the rabbits that Chancellors yank from the hat with the greatest flourish on Budget days tend to involve Income Tax. That most political of Chancellors, Gordon Brown, was notoriously fond of tinkering. His creation and subsequent abolition of the 10p “starting rate” and the introduction of the 50p “additional rate” were more about theatre and political messaging than about raising revenue efficiently. George Osborne made dramatic changes to the thresholds where people start paying Income Tax, with the result that 43% of adults now pay no income tax at all. And all Chancellors, now including Kwasi Kwarteng, love most of all to proclaim ‘a penny off the basic rate’.

Further complicating matters, the parallel National Insurance scheme, an income tax in all but name, adds further (weekly!) earnings thresholds and rates. The two systems should have been merged long ago; the primary reason that they haven’t been is that pensioners don’t pay NI, and no government has so far felt it prudent to add an additional 12% tax to the incomes of the people most likely to vote in general elections.

The complexity of the two systems makes it quite tricky for an individual to work out their total tax liability and how it might change with increased income. At one time, when calculations had to be done manually by a payroll clerk it might have made sense to have a simple threshold and rate system, but there is no longer any such rationale, as computers do all of the necessary calculations.

Tax bands are also a blunt system which does nothing to assist good governance. The focus on marginal rates is misleading, as it is the total effective rate that taxpayers experience, ie the total deduction from their pay packet. Relatively insignificant measures, such as abolishing the additional rate band, also have their significance inflated well above their impact on revenue. For example, abolishing the 45p rate means that someone earning £160,000 will save just £500 per year from their £64,000 bill.

It is also inflexible – changes can apparently only be made in an increment of ‘a penny’ across the majority of taxpayers (83% of taxpayers are on the basic rate) and there are cliff edges where the marginal rate changes significantly, as high as 62% in the £100,000-£120,000 band. This can discourage income progression into that band if the likelihood of ever exceeding it is low. (And gradual withdrawal of child support at £50,000 can create still higher marginal rates.)

In short, the whole system is a crude mess, subjected to endless tinkering and clever wheezes from Chancellors over the years, and prone to distorting both policy and the reporting of policy. It’s time the whole system was replaced.

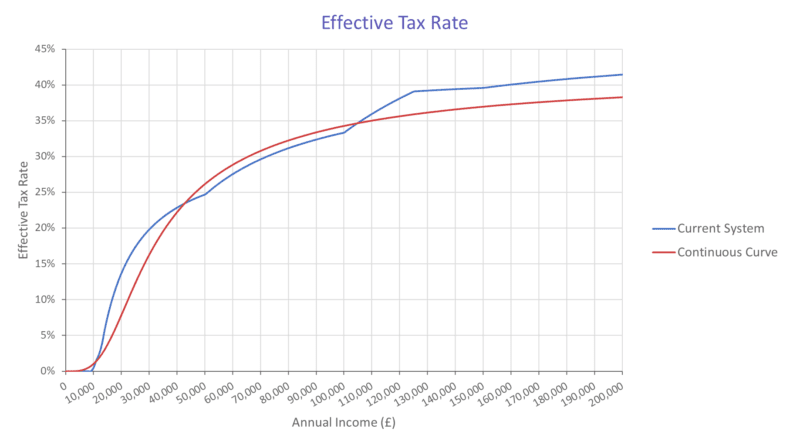

A far more elegant alternative would be to use a continuous curve to set the effective tax rate across the entire income distribution. Consider the following chart:

The blue line shows the current effective rate of tax, including both Income Tax and National Insurance. It’s not an easy line to draw – the strangely segmented nature of it is due to the current banded system of marginal tax rates and it requires every point to be calculated separately.

The red line shows a more rational alternative – a smooth s-shaped curve, defined by just five parameters plugged into a function used frequently in bioanalytics and in other science and engineering applications.

The ease of calculation is one benefit, but there are several others. For one thing, there are no longer abrupt changes to the marginal rate; rather, it is a gradual increase in the effective tax rate, which removes any ‘cliff edges’ or disincentives to earn more.

But perhaps most importantly, the proposed method would give the Chancellor far more subtle and flexible means of adjusting the level of tax paid by people across the income distribution simply by tweaking the parameters of the curve.

For example, the maximum level could be raised slightly such that all taxpayers pay a fraction more, but without changing the basic shape of the curve, so everyone’s share of the tax burden remains constant. Increased revenue can therefore by achieved without privileging one group above another.

Similarly, shifting the curve slightly to the right would provide a tax cut to the lowest paid, but without changing what higher-earners pay. The steepness of the curve can be altered, further changing the rate at which different earner pay. Because of this, it isn’t just an approach that lends itself to one particular philosophy, but one that’s flexible enough to describe any number of options.

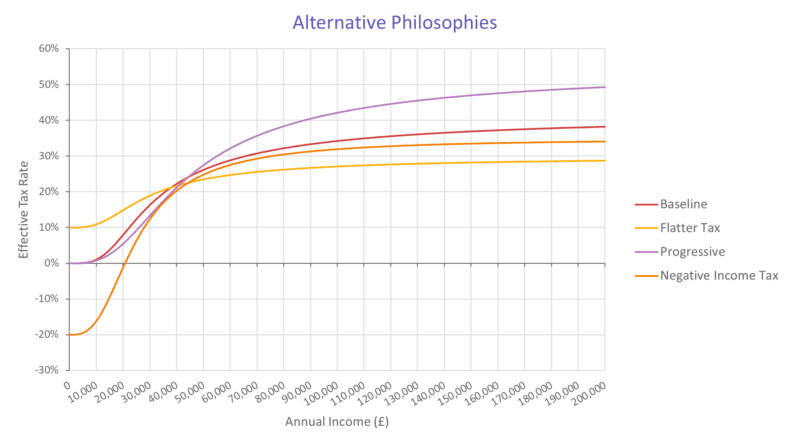

The following chart illustrates this with a few possibilities. For example, a steeper curve with a higher maximum limit could be a more progressive system than that depicted above, while a flatter tax broadens the tax base but has a lower maximum (tending towards the flat tax system beloved of economic liberals). You could even implement a negative income tax as part of simplifying the welfare state as well.

Crucially, it is far easier to compare the tax actually paid by an individual under these different regimes than under the current system. As such, the reporting of changes on Budget day would hopefully be more likely to reflect the reality of the changes.

As the current government has made tax simplification one of its primary goals, and paid a considerable political price to accomplish that, it could do far worse than to implement a solution of this nature. Additionally, if they were to choose to tax capital income from dividends, interest and rent in the same way (which are currently subject to various other sets of thresholds and rates), the entire tax system could be made far simpler and far more transparent at a stroke.

The last week has shown that Kwasi Kwarteng is keen to earn himself a reputation for boldness – this is a chance to create a positive reforming legacy that would completely eclipse his accidental spooking of the bond markets. How about it, Chancellor?

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.