News of yet another government consultation would ordinarily provoke little more than eye-rolling. When it comes to gene editing, however, it could be the start of something truly exciting. And if, as he has hinted, the Environment Secretary does decide to adopt a more liberal regulatory regime for the UK, that would certainly be no bad thing.

Until now, British scientists and farmers have been restricted when it came to experimenting with edited crops due to the EU’s excessively cautious approach. Brexit offers the chance to go in a different direction.

So what is genetic editing? At its simplest, it means altering an organism’s genetic code. Unlike genetic modification, it does not involve the insertion of any new genetic material, but is about selecting for desirable characteristics a plant may have, and encouraging their expression of them.

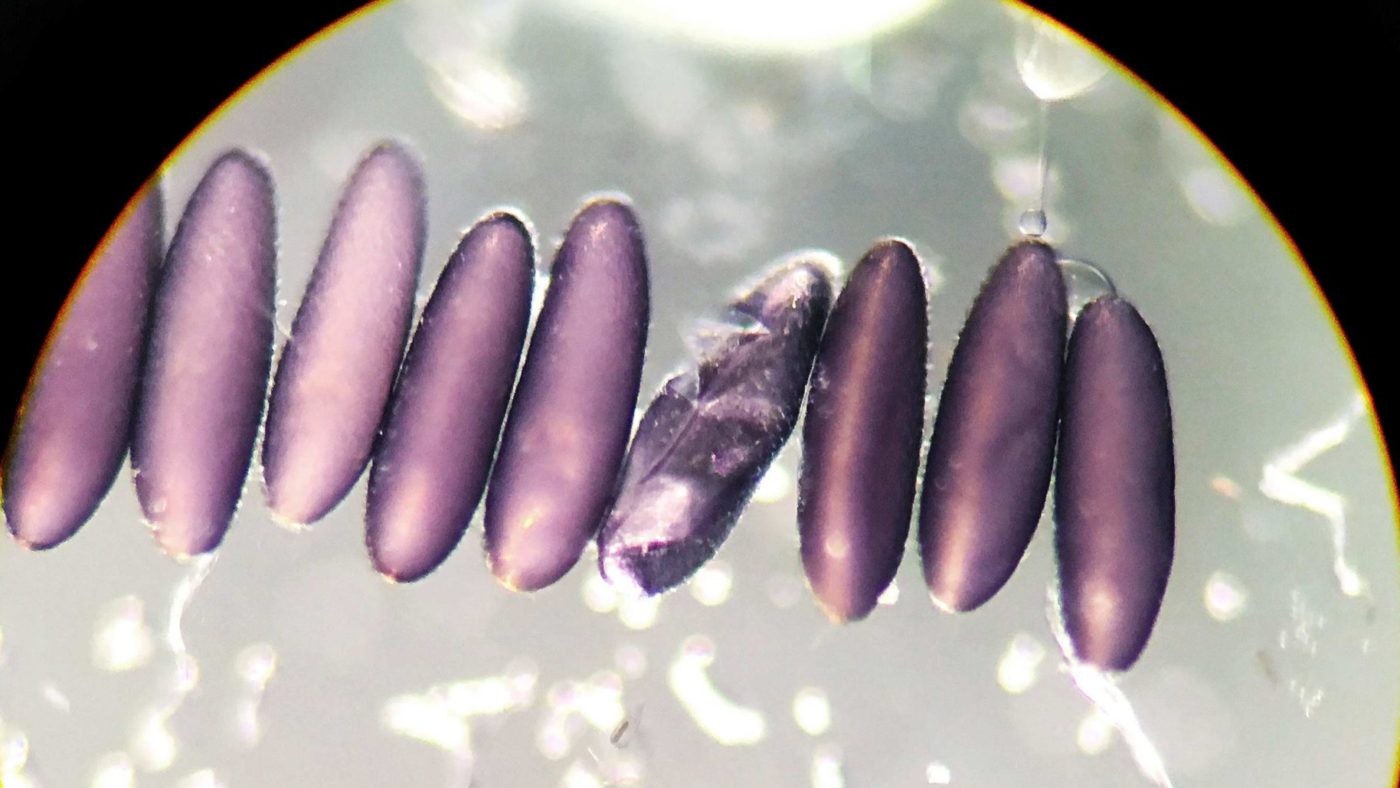

Another way of thinking about genetic editing is that it is simply what farmers have been doing for thousands of years, only sped up. Just as a cereal farmer might try to breed varieties of wheat which produce lots of grains, genetic editing can accelerate this process – arriving at the same destination, just much quicker, and at less cost.

Indeed, while the benefits of gene editing are numerous, one of its most promising applications is how it could be used to protect the natural environment.

The most obvious application of genetic editing in crops is to boost yields. By selecting for traits that promote growth, plants can be engineered to deliver the maximum amount of produce for any given acre of land. In practice, this might mean bigger tomatoes or more strawberries.

Why is this good for the environment? Principally, it means we can grow the food we require in less space. Arable land that is no longer needed for farming could be rewilded with trees and converted to habitat for wild creatures. This ‘land sparing’ aspect which genetic editing could unleash is probably the single biggest environmental benefit we stand to realise from the widespread adoption of gene-edited plants.

But the potential windfall doesn’t stop there. Genetic editing could help us to select for an array of different desirable characteristics, all of which can help improve the environment.

We could, for instance, design crops which need little or no fertiliser to grow. Given that the production and application of fertiliser creates greenhouse gas emissions and diminishes air and water quality, the sooner we can do without it, the better.

In a similar vein, crops could be enhanced so that they are more resistant to pests or diseases. Theoretically, this could negate the need for pesticides, fungicides, or other substances farmers use to keep threats at bay. This would be a reprieve for various pollinator species – critical actors for so many ecosystems, which currently get caught in the chemical crossfire all too often.

Indeed, plants could be altered so they are hardier not just against pests, but also the weather. Crops which can tolerate warmer, drier climates in certain areas, and those which can cope with deluges of rain, will only become more important as the climate changes due to global warming. This could be a nice benefit in the UK, or a lifeline in developing countries – where harvest failure can literally be the difference between life and death.

The virtues of more robust varieties of crops aren’t limited to when they’re growing, however. Once picked, another issue kicks in – the potential for food waste. When food rots, it produces greenhouse gases – and approximately 8% of world anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions come from food waste, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. A novel way to prevent against this is to extend perishable products’ shelf lives, something genetic editing could well assist with.

Finally, genetically editing plants has a role to play outside of the food system, too. Research institutes are already exploring how organisms could be modified so that they can help reduce the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. A forest of genetically edited trees, with enhanced abilities to sequester extra carbon and lock it into their roots, trunks and branches represents an ingenious, if slightly eccentric, way to tackle climate change head on.

Without doubt, there will be those who will oppose any relaxation of the current rules. Anti-science campaigners captured Brussels and they will do their best to capture the newly independent Westminster too. But the Government should not be cowed by their efforts.

Genetic editing is perfectly safe – and by protecting the environment, it can help to prevent real dangers, not least those caused by climate change.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.