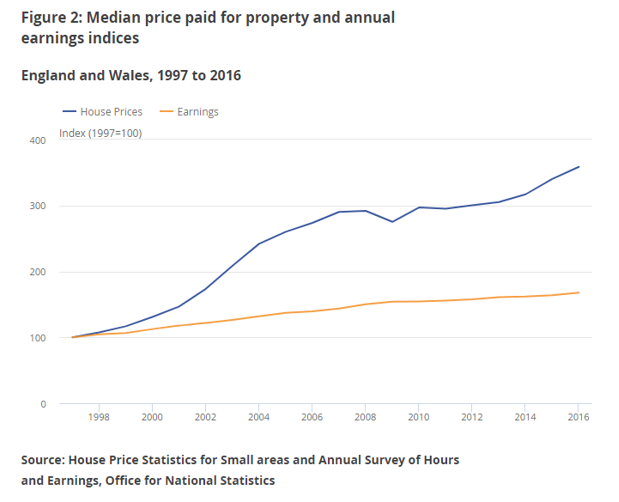

We tend to conceptualise the housing crisis in terms of affordability – and justifiably so. Over the last two decades, the ratio of median house prices to earnings in England and Wales has more than doubled.

Back in 1997, house prices represented, on average, around 3.6 times workers’ annual gross full-time earnings. By 2016, however, prospective buyers could expect to spend around 7.6 times their annual earnings on purchasing a home. Drilling down to a regional level yields even more dramatic results, particularly in London and the South East, and cities like Oxford, Cambridge and Bristol.

No one doubts this worrying state of affairs, but I sometimes wonder whether we may be missing the true scale and severity of the situation. After all, the housing crisis has many hidden, human, costs that can be easily lost in the data. Firstly, exorbitant rents mean less disposable income – and correspondingly high opportunity costs.

One recent study showed that Londoners and residents of several other cities are on average spending more than a third of their monthly salary on rent, before even considering household bills or council tax payments. In practice, this equates to billions of pounds in lost consumer spending. Consider the cash boost to UK businesses – and uplift to our overall quality of life – if some of this rental expenditure could be freed up for other uses.

Another product of the housing crisis? Perpetual teenagerhood. The number of adults aged between 21 and 34 still living with their parents today has risen by more than 700,000 since 2005, with the increasing difficulty of getting a toehold on the housing ladder one of the key factors.

Of course, there’s nothing innately wrong with living with one’s parents, but the problem is that longer periods spent at home (often, while saving up for a deposit), mean that major life events can be taken off the table as a result. Conservatives, whether small or large “c”,

should be particularly concerned by these developments.

The charity Shelter has estimated that 59 per cent of people aged 21-34 have been forced to postpone marriage, starting a family, or moving into a job. This latter point has harmful knock-on effects, for labour mobility is a much-overlooked factor in generational inequality.

As the Resolution Foundation has outlined, Millennials (Generation Y) have so far been 20-25 per cent less likely to move jobs voluntarily than members of Gen X at the same age, following a trend that began in the early 2000s. And, by moving for work less frequently, this cohort loses out on significant pay rises. Switching jobs, rather than staying with the same employer, is almost always associated with an earnings boost, but the highest pay premium of all is reserved for those willing to relocate to a different region altogether.

Such trends are partly explained by Millennial loyalty to employers, but are also likely exacerbated by the housing crisis. Just as the burdens of stamp duty deter older residents from moving home or downsizing, high moving costs and the growing average spend on

deposits conspire to lock younger workers into existing accommodation, leaving them worse off as a result.

There are other, even less obvious, by-products of the housing crisis. As anyone who’s ever tried to move in London with a cat or dog will attest, landlords are notoriously reluctant to accommodate our four-legged friends. According to the Dogs Trust, 78% of owners have struggled to find pet-friendly rentals.

While it’s quite understandable that many landlords would prefer to avoid fur and mess, the fact they can afford to be this selective in the first place is surely symptomatic of wider supply-and-demand issues. The UK is, famously, a nation of pet lovers, with nearly 50% of us owning some kind of domestic animal. In a less dysfunctional market, the decision to exclude vast swathes of potential tenants in this way simply wouldn’t be economically viable.

Or consider the implications for interior design. Many landlords are now reluctant to let tenants add personal touches to their rental accommodation, for instance by painting their walls a different colour or making minor alterations during their tenure.

This is partly a result of changing decor trends, but also derives from economic realities. Just as a shortage of supply has allowed landlords to rule out pets in areas of high demand, so too can they prohibit tenants from making changes to their rental property, given the ferocity of competition for housing stock.

The housing crisis doesn’t just mean higher rents, then, but also condemns renters to impersonal, minimalist homes. My mum’s house was recently profiled in a Daily Mail feature examining “Britain’s tackiest interior design trends” (“Meet the women who are keeping them

alive!”), showcasing her Victorian-style chintz curtains and William Morris wallpaper.

I suspect her inclusion is only partly down to eclectic taste. In an environment where more people could decorate their homes as they wished, my mother and her eccentric wallpaper patterns wouldn’t be such an anomaly.

These may seem like minor issues in the grand scheme of things, but are worth bearing in mind all the same. We are rightly outraged about rising housing costs. But where is the anger about the fact that, due to entirely avoidable government policies, millions of us lack

the freedom to keep a pet or even nail a few shelves onto the wall?