This is the CapX Weekly Briefing

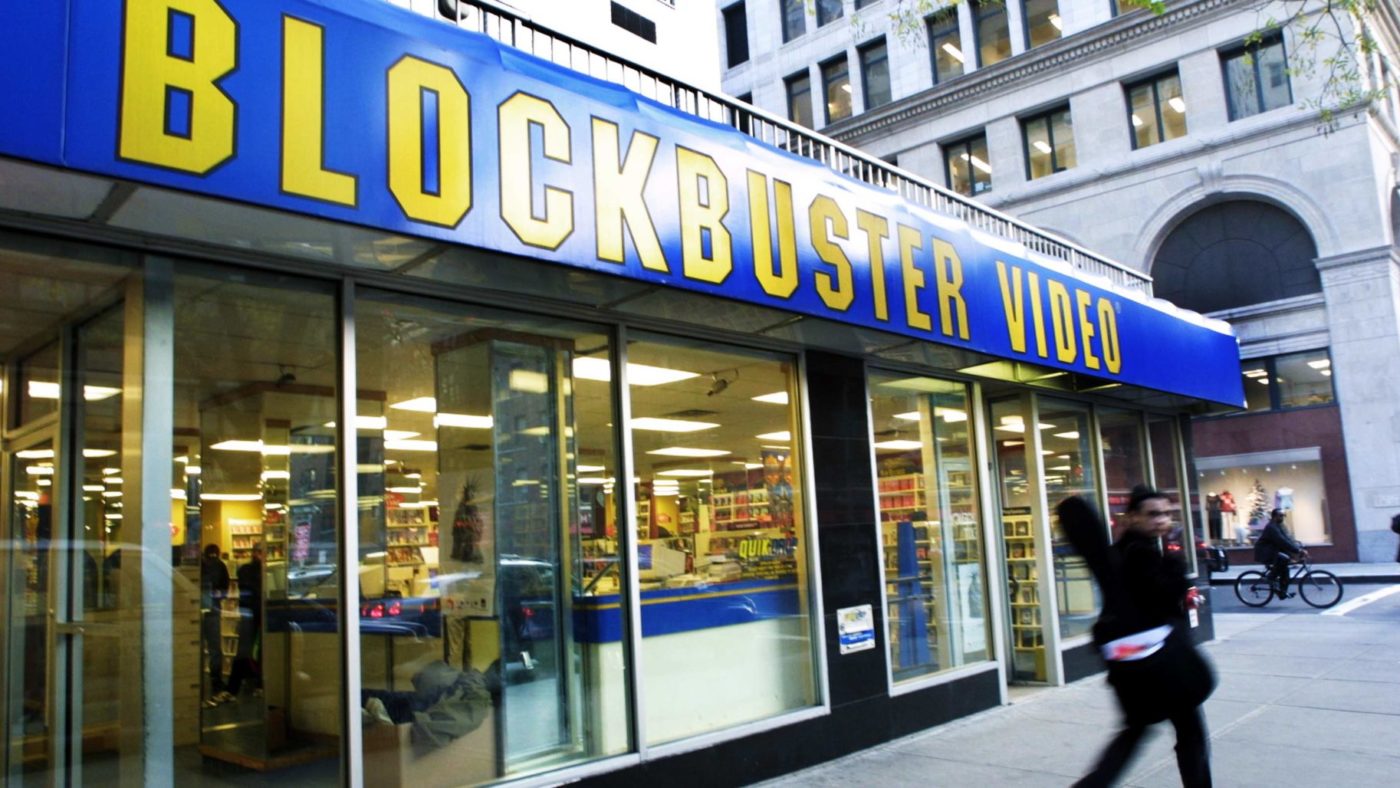

Once upon a time there was a company that rented videos to over fifty million members, from nine-thousand stores worldwide. This week, that company joined forces with Airbnb – to rent out a sofa in their only shop left. But the story of Blockbuster is not that of a fairy tale turned nightmare, but a parable of the market economy – and, indeed, a source of hope.

In its heyday, Blockbuster provided a service that people wanted and couldn’t get elsewhere, at least not to a comparable standard, choice or price. Then came the internet, ripping the carpet from under them. And while Blockbuster was able to flap its arms in the air for a brief moment – instigating various attempts to arrest their fall – they couldn’t prevent crashing to the floor. Suddenly the business model just didn’t work. The need – and comparative hassle – of travelling to a store to rent a film from a limited selection just withered away as the web opened up a vista of easy choice and lower costs.

Fast forward to today and the last store – in Bend, Oregon – is described by its owner as ‘an ode to movie magic, simpler times and the sense of community that could once be found in Blockbuster locations around the world’. I remember sticky carpets, strip lighting and recalcitrant staff in my local outlet, but I guess that’s beside the point. In the end the nostalgia of past experience becomes your only selling point.

Part of the power of consumerism is, of course, its ability to shape the imagination – and we shouldn’t therefore dismiss those whose natural impulse at a firm’s obsolescence is one of sadness. For many, Blockbuster forms part of the vision of their youth – a vision we hold deep within us long after the visible signs of it have gone. A brand disappearing, then, can feel like a tiny piece of ourselves drifting off too; a little, comforting link to the past, severed.

Yet there’s a reason why certain companies all but disappear, trading only on memories. It’s worth repeating that, far from the narrative of corporates exploiting Average Joe, the consumer market is driven by people, and people have the power to vote with their wallets, encourage greater choice, reduce prices and fell any business, however large, that doesn’t provide what they want. Some exploitation, that. The case of Blockbuster’s is no different, with Average Joe calling the shots – and plenty of people preferred the cheaper, more convenient alternatives.

But it’s hard to counter nostalgia with raw numbers and price differentials – more is needed. And so enter hope.

For the broader story behind this is not one of death but of renewal. Because what finished off Blockbuster was not only a failure to adapt, but the irresistible force they failed to adapt to: the innovation of others. Blockbuster became, well, just bust, because the internet unleashed forces which most people couldn’t even imagine, let alone see coming at the time of the video rental chain’s rapid expansion.

It’s easy to forget how quickly the internet has changed our world – and, for all its obvious faults, there have accrued remarkable social and economic benefits to those from the poorest countries in the world to the West’s greatest Blockbuster fans and beyond.

And that irresistible, blindingly fast development – and the innovation it unlocked – should offer some comfort. For in these times, when the future can feel frightening, the lesson of Blockbuster’s fall is not that all things must die, but that life-enhancing things will continue to be born. We cannot know when, we cannot know what – but rather than fear the future we must embrace it, and adapt.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.