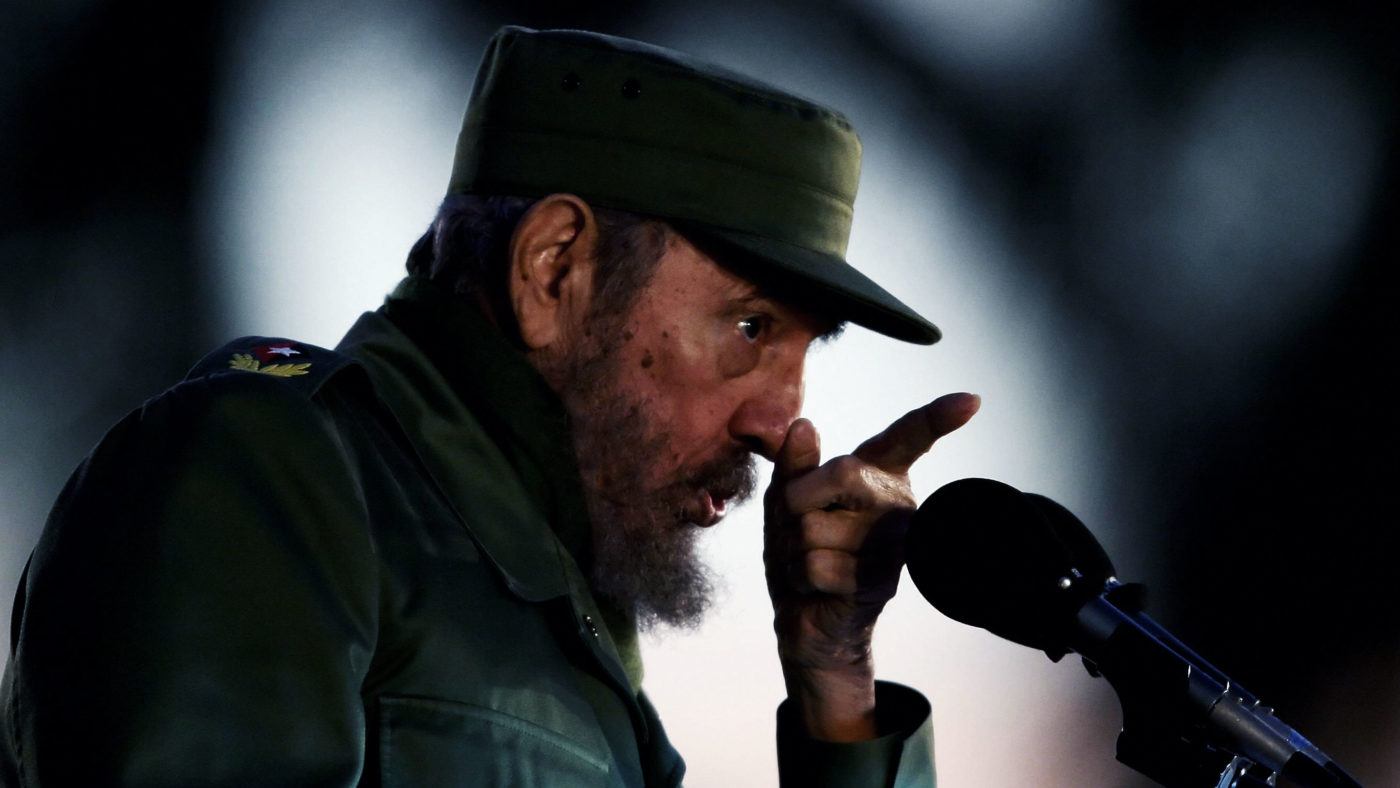

In death, as in life, Fidel Castro was an ideological Rorschach Blot. Some praised a revolutionary hero. Others excoriated a brutal dictator. Still others tried, uneasily, to split the difference.

On the “revolutionary hero” side of the ledger were, inevitably, Castro’s old comrades on the British Left.

George Galloway called “Comandante Fidel” the “man of the century” and “the greatest man I ever met” (the shade of Saddam Hussein is doubtless huffing in indignation).

Ken Livingstone praised him for building a “very open and relaxed society”.

And, of course, Jeremy Corbyn declared him “a massive figure in the history of the whole planet… he will be remembered both as an internationalist and a champion of social justice”.

What’s interesting here isn’t so much the sentiments – which were pretty much as expected – as the logic.

This was that, for all its failings, the Castro government was engaged in the greatest of projects: resistance to American imperialist capitalism. Given that said economic system is the world’s great evil, anything done to oppose it must by definition be good – or at the very least a lesser evil.

In particular, even if it had erred, Castro’s government could be forgiven because it was on a wartime footing – the plucky Asterix to America’s Roman empire.

As Seumas Milne, Corbyn’s consigliere, wrote in a 2003 column for the Guardian, “US hostility to Cuba does not stem from the regime’s human rights failings, but its social and political successes and the challenge its unyielding independence offers to other US and western satellite states”.

By this extraordinary logic, Castro’s crimes should be blamed not on Castro, but on America. “The greatest contribution those genuinely concerned about human rights and democracy in Cuba can make,” Milne concluded, “is to help get the US and its European friends off the Cubans’ backs.”

Similar sentiments crop up in another small slice of left-wing history: Another World Is Possible – a Manifesto for 21st-Century Socialism, written in 2010 by John McDonnell.

Unaccountably, this text has vanished from the website of the hard-left Labour Representation Committee, McDonnell’s redoubt during the long years in the wilderness. But a few months back, I tracked down a copy.

Sure enough, one of McDonnell’s manifesto commitments was “support for the government and people of Venezuela, Bolivia, Cuba and other countries pursuing policies that create alternatives to the market economy and the control of [trans-national corporations], the WTO and IMF.”

In other words, support for Cuba was not just admirable. It should be one of the central planks of British foreign policy – because anyone creating an “alternative to the market economy” was automatically to be supported.

This is, of course, the opposite of the truth. Castro might have been an inspirational figure to many. He was also, as Andrew Neil has been pointing out on Twitter, a dictatorial tyrant:

On Castro's death, remember Huber Matos, comrade in arms. Attacked Castro's ties to Moscow. Show trial. Torture. 20 yrs prison. 16 solitary

— Andrew Neil (@afneil) November 27, 2016

Even leaving aside his human rights record, economists are clear that it was Castro’s own economic mismanagement, rather than US sanctions, which played the leading role in immiserating Cuba’s people.

Yes, he trained doctors. But he also presided over a country in which GDP/head in PPP terms was roughly the same in 1959 as 1999, and living standards in 2007 as 1985. It’s actually a perfect illustration of the point I made in my weekly briefing email for CapX (sign up here) about the market’s role in delivering prosperity.

Anyway, my intention here isn’t to litigate Castro’s record, but to make two bigger points about the mentality of his fellow travellers here in Britain.

The first, as I mentioned above, is the moral blindness brought on to a hostility to America. Part of this was the idea that even if Castro did bad things, we have no right to criticise them because our own societies are hopelessly tarnished, too.

Corbyn, for example, acknowledged this week that Castro’s regime had “excesses” – but insisted that the same could be said of any government.

More instructive, however, is his foreword to a 2011 book, Imperialism. Corbyn noted there that “all countries encourage a very nationalist form of history teaching, and from that stems racism and perverted feelings of superiority”.

And if we could cast aside those nationalist, racist feelings of superiority, Corbyn wrote, counties like Cuba had much to teach us. It had, he said, “developed a quite independent foreign policy and enormous respect and stature among the poorest people, particularly in Latin America”. Leaving aside, of course, that point that for the poorest people in Cuba, it had been a disaster.

For Corbyn, Castro’s policy was good precisely because it was independent – of America and of capitalism. As he also wrote, “free market capitalism cannot provide for everyone, or sustain the natural world. Its very imperative is of ever hastening exploitation of all resources including people, and it needs armies and weapons to secure those supplies”.

Fortunately, “the political appeal, unchallenged in the 1990s, of this concept is fast fading by a combination of Islamic opposition and the radical popular movements of landless and poor peoples in many poor countries.” Hooray for al-Qaeda!

The second point is the glaring lack of intellectual curiosity – of self-examination – on show here.

It is unfair to say that McDonnell and Corbyn and Milne have not had any new ideas in the past 30 or 40 years. McDonnell, for example, announced in that 2010 book that globalisation had replaced capitalism as the greatest evil in the world, as the child replaces the parent.

But the bizarre thing here is that the columns and books I’m quoting were written not in 1959, when Castro took power, or the 1970s and 1980s. They were written decades after it had become clear what kind of regime Castro’s was, and how deeply it had failed, even on its own terms – after it had subsided from being a revolutionary inspiration to a failed experiment.

I’d say that writing that sort of stuff at that sort of time is like writing in defence of Stalin after Robert Conquest had exposed the full extent of his crimes – except, of course, that Seumas Milne has previous there, too.

And this is what is so extraordinary, and so alarming, about the hard left. Whatever the changes in politics, society or technology, whatever the twists and turns that history takes, they cling to their original analysis – to the student insights developed in student bedrooms.

This is not, of course, a problem just on the left. But whatever your political persuasion, there has to come a moment when the chasm between your beliefs and the reality forces at least some self-examination.

Castro’s tragedy, and Cuba’s, was that he could never bring himself to that moment. The same could be said of those now in charge of Britain’s Labour Party.