The Beveridge report is now synonymous with the creation of the NHS and the modern welfare state. Yet if you return to its pages, you find a very different vision of the future.

Beveridge certainly wanted to fight against the ‘five giants’ – idleness, ignorance, disease, squalor and want. And he certainly wanted to extend provision, in his famous phrase, from ‘cradle to grave’. But there was another crucial element: the help you got from the state should reflect the extent to which you had put in. As he put it, ‘benefit in return for contributions, rather than free allowances from the State, is what the people of Britain desire’.

For the past three years, the Centre for Policy Studies and Public First have been working together to answer a simple question: why have voters lost faith in the welfare state? In the decades prior to the pandemic, support for welfare eroded sharply. This has happened with no other policy area, and in no other country that we could identify.

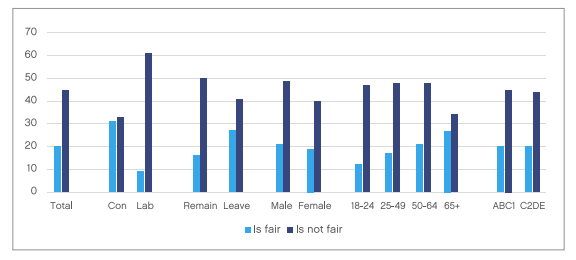

Our investigation, involving focus group and polling work carried out by Public First and YouGov, came to the conclusion that the key issue was fairness. By a 2:1 majority, voters did not think the welfare state was fair. And they thought this for two reasons: first, because it was not doing enough to protect those in genuine need (by which they invariably meant the disabled and those who physically could not work). And second, because it was not doing enough to recognise the connection between effort and reward – either to push people from welfare back into work, or to recognise those who worked hard and contributed.

Do you think the current welfare system is fair?

(Source: YouGov polling for CPS, February 2021)

And they had good reason to think so: because in the decades since the Beveridge report, we have systematically stripped out the contributory element from our welfare system. To give one very simple example, if you have savings of more than £16,000, and you become unemployed, you cannot claim benefits until you have spent your way through that money. Even then, you will still receive a lower rate of payment until you are on your last £6,000.

This is, fairly obviously, the exact opposite of doing the right thing. It is also, as our polling found, hugely unpopular among every kind of voter – especially since the number of claimants affected by such rules has risen tenfold during the pandemic.

Our new report, ‘Fair Welfare’, also found strong support for restoring contribution to the welfare system. One way of doing this, which we propose in the report, would be to restore ‘the stamp’, the symbolic token that people had paid in, and therefore deserved to take out. We suggest a new digital Contribution Card, which tallies the length of time you have paid in for. For every five years you have paid in, you would receive a £5 uplift in your Universal Credit payment for the first year of unemployment – and, crucially, be exempted from the bureaucratic hurdles around finding a new job for an extra three months, up to a maximum of a year.

To test this, we asked people what level of benefits people should get if they became unemployed after paying in for various different periods. As the time spent in the workforce increased, so did their generosity – with the favoured level of benefits moving from bare subsistence up to the average wage.

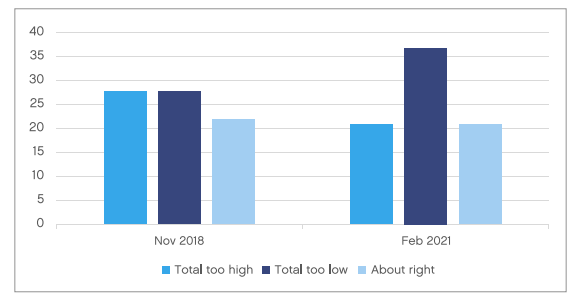

Views on the level of benefits for the unemployed

(Source: YouGov polling for CPS, February 2021)

The report also has important things to say about the current debate over Universal Credit. A favoured argument on the left is that the pandemic has made people realise quite how stingy our existing benefits are, which is why the £20 emergency uplift brought in by the Chancellor needs to be made permanent.

Having repeated our original YouGov polling in the wake of the pandemic, we are uniquely positioned to respond to such claims. It is true that there has been a shift in attitudes on benefits: in September 2018, the numbers claiming that benefits were too high and too low were roughly equal, whereas by February 2021, ‘too low’ had a 16-point lead.

At the same time, however, voters also said that they did not want taxes to rise to pay higher benefits. And compared with removing it completely, or giving it only to those with a track record of contribution, maintaining the blanket uplift was the least popular option. (That perennial left-wing pipe dream, the Universal Basic Income, did even worse.)

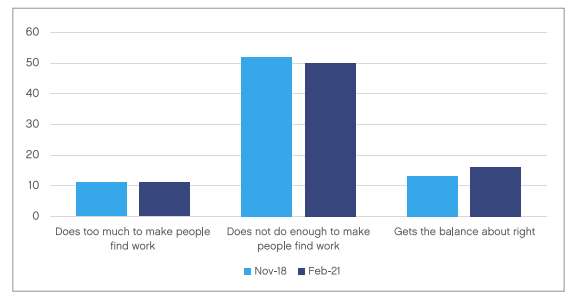

In fact, the most striking thing about our polling was that fundamental attitudes appeared completely unchanged. By a huge margin (roughly 50% to 10%) voters in both 2018 and 2021 claimed that the benefit system currently does too little to make people find work, rather than too much. The most popular reasons for voters to think the welfare system was unfair were, in order, ‘It is too generous to those that can’t be bothered to seek work’, ‘It is too vulnerable to fraudulent claims’ and ‘It is too harsh on those that cannot work, like the disabled’. Only then came ‘It does not give people enough money to survive upon’.

Views on work search requirements for benefit claimants

(Source: YouGov polling for CPS, February 2021)

The rest of the report is equally fascinating. It shows that Britain does not, contrary to the propaganda, have a uniquely stingy welfare system. It shows that the public have, in many respects, a better understanding of the system than the experts. It confirms that one of our big problems is that we withdraw benefits too quickly as people return to work – which is why we suggest that the £20 uplift should be replaced by a cut in the rate at which UC is withdrawn, doing more for people who go back into work at roughly half the price.

And it also shows that there are areas where the system should indeed be more compassionate – such as cutting the wait for the first benefit payment, or paying people on uncertain incomes weekly rather than monthly.

We expect there to be a healthy debate over our arguments. But what is particularly encouraging, over the course of this project, has been the extent to which contributory welfare – returning to that central Beveridge principle – has gained traction.

When we started our work, some of those we spoke to could barely contain their scorn at the idea. Yet a recent report from the Government’s own Social Security Advisory Committee recommended reversing decades of DWP policy and strengthening the contributory benefits system. The report argued that the contributory principle of ‘something for something’ has been ‘progressively eroded’ and that ‘the time has come to restore at least an element of that’.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies, similarly, argued recently that ‘the lack of contributory benefits in the UK has become more salient in the coronavirus pandemic, as a large number of workers have become exposed to substantial losses in income’. The Resolution Foundation have stated: ‘When the crisis has passed, there is a very good case for reviewing the balance between contributory and means-tested benefits.’

The subject is also beginning to attract cross-party attention. Last summer, the Labour Party’s Shadow Work and Pensions Secretary, Jonathan Reynolds, expressed his own conviction of the need to revitalise the contributory principle. He said: ‘One of the reasons that support for social security has diminished amongst parts of the country is the sense that people put into the system and they don’t get anything out of it… I feel if you have made greater contributions to the system, there is an argument that you should receive more out of that system.’ Frank Field, former Labour minister and Chair of the Work and Pensions Select Committee, expressed similar sentiments in a policy paper published in September 2020.

We do not need to rip up the welfare system and start again. We are not, compared to other OECD countries, either miserly or regressive in our approach to welfare. Rather, we need to do what almost every other developed country does, and reintroduce a clear link between contribution and reward, and a clearer sense of fairness within it. That way, we can build a welfare system which rewards those who have done the right thing in the past, that protects the poorest, weakest and most vulnerable, and that enjoys the trust and support of the British public.

‘Fair Welfare’, by James Heywood and Jonathan Dupont, was published yesterday by the Centre for Policy Studies

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.