Is capitalism finally coming to an end?

Karl Marx anticipated that moment. Joseph Schumpeter also saw it coming. And just like they predicted (we are now led to believe), capitalism is getting caught in “the perennial gale of creative destruction”. For Marx, capitalism was a system of economic oppression, but like Schumpeter he had an admiration for its irrepressible force of coming up with new technology and ideas. They would destroy jobs and capital – and all that are solid would melt into air. But capitalism could boost innovation like no other system. In the end, capitalism would become a casualty of its own success: it would innovate itself to death.

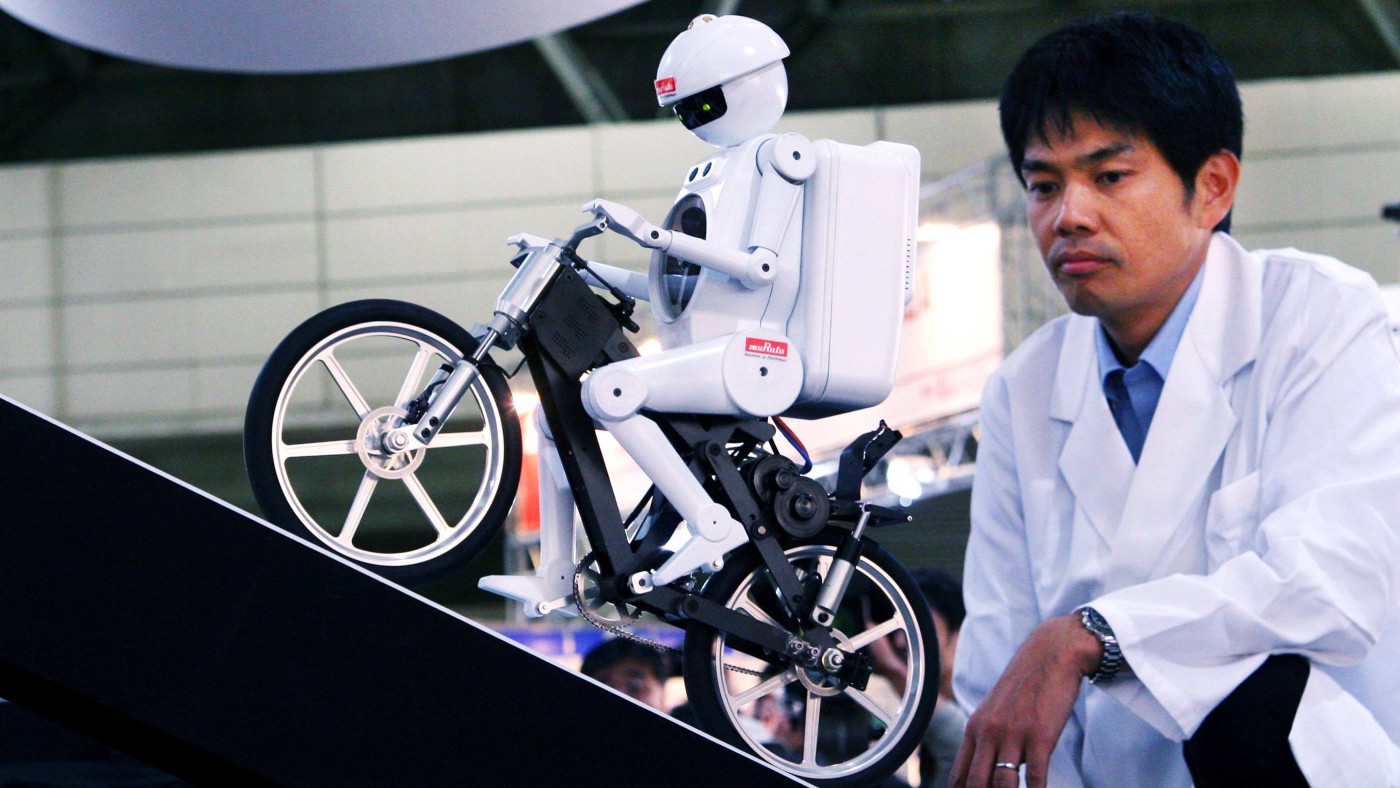

So is this the end? A cabal of techno-dystopians appears to think so, and it is easy to see why. Techno angst has been growing in the West as we are fed daily with scare-stories about 3D-printing, supercomputers, and artificial intelligence. As post-crisis unemployment remains stubbornly high in most parts of Europe and the United States, a lot of people seem to think the technological blitz against employment already has begun.

Techno-dystopianism also gets respectable academic support from scholars like Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAffe, authors of bestselling Race Against the Machine and The Second Machine Age. In their view, it is just a matter of time until computer algorithms are so powerful that they’ll practically run the economy. The tech aristocracy has also weighed in. Eric Schmidt, the chairman of Google, sent a shiver down the spine of business executives at Davos earlier this year by prophesising new computer technology to do away with all these jobs that automation could not yet reach. A group of Oxford economists gave a more modest figure in a paper from last year, yet still claimed that almost half of all current jobs in the United States are at “high risk” of being squeezed out by computerisation.

And so the vast majority of us are travelling on a one-way ticket to economic Netherworld, forever demoted to the dispossessed proletariat and poor economic expectations.

But modern techno-dystopians get it wrong. History is full of clever people that have made specious claims about how new technology will starve societies by making people redundant. But they have always been wrong. And like in the past, new technology in the future will make societies richer. Jobs will be destroyed, for sure, but new and better-paid jobs will be created.

The problem is not that techno-dystopians are stoking fear, but that they are masking the real innovation problem in our economy: the speed of technological change has actually slowed down in the past decades. Furthermore, the way capitalism has evolved under that period suggests we are not going to get faster innovation in the future.

Governments are certainly responsible for the slow down. Market regulations have continued to expand, and now clog up the arteries of innovation. Just ask a biopharmaceutical innovator with a powerful new drug in the pipeline how difficult it is to get a product to pass the regulators. Or think about the regulatory and political battles that the app-based taxi ride-sharing company Über has had to fight in Europe. You’d think Über would be a welcome competitor in over-priced and under-serviced taxi markets in Europe. But governments across Europe are trying to cut them out of the market by arcane licenses and regulations, designed to protect incumbent taxi oligopolies. And what happened to that magnificent drone, potentially revolutionising the transport market, unveiled by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos last year? The U.S. government decided it can’t be used until new regulations have been designed.

Private companies share a good part of the blame, too. In the past decades, the economic system we call capitalism has become dry, bureaucratic and risk-averse. Multinationals shun uncertainty, which is an essential piece of all investments in innovation, and have cut down on genuine innovation spending. Generally, capital expenditures have been shrinking and the investments necessary to get new innovations to ripple through entire economies are simply not made.

Under the pressure of institutional investors, corporate leaders favour strategies that give a small but stable return on investment. All these conservative money-holders – pension funds, sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) et cetera – are draining the risk-taking out of capitalism. In this new capitalism evolving now, governments are also taking control of corporate boardrooms. The Norwegian SWF alone owns almost 1.5 percent of all global equity. Soon, the finances for corporate innovation will be controlled by government officials in Abu Dhabi, China, Norway, and other countries with sizeable state funds for investment.

Executives are already responding to that development. They hoard cash on their balance sheets to protect against an aging corporate asset base. They put more energy into mergers and acquisitions than innovation. In the history of capitalism, the corporate world has never been as well-capitalised as now. Remarkably, over the past few years companies have become net lenders of capital in the economy. Without good ideas for how to spend capital on raising future profitability, corporate leaders favour share buybacks. A year ago Apple had 145 billion U.S. dollars in cash, apparently more than the U.S. Treasury at the time. This great pioneer of modern technology reportedly spends more money on lawyers than on research and development.

The future of capitalism is not a techno-dystopia – Western economies actually need an innovation revival to raise productivity and economic growth. But current capitalism is no utopia either. Its ability to foster and diffuse innovation has weakened. It is shackled by risk-averse bureaucrats in governments and companies. Under their reign, jobs will be destroyed – but because of innovation inertia, not innovation enthusiasm. Innovative capitalism can still generate progress and growth. New innovative start-ups will hopefully invade many more sectors than the digital world. Government officials, financiers, and executives have conspired to slow down innovative competition. Capitalism is now bound. Let’s release it!