How should we deal with governments that act in a bad way, for example by attacking their neighbours? Today an increasingly popular tool that governments turn to is economic sanctions. This makes some sense: it is an easy choice and shows that politicians are doing something.

The problem is that sanctions often have the opposite effect. They undermine voluntary market exchange – and through that freedom in the countries targeted by sanctions. The researchers Dursun Peksen and Cooper Drury looked at many different sanctions that were introduced during the years 1972 to 2000. They found that the sanctions, both immediately and in the long-term “significantly reduce the level of democratic freedoms in the target”. Rather than fostering democracy and peace, sanctions reduce political rights and civil liberties in the targeted state.

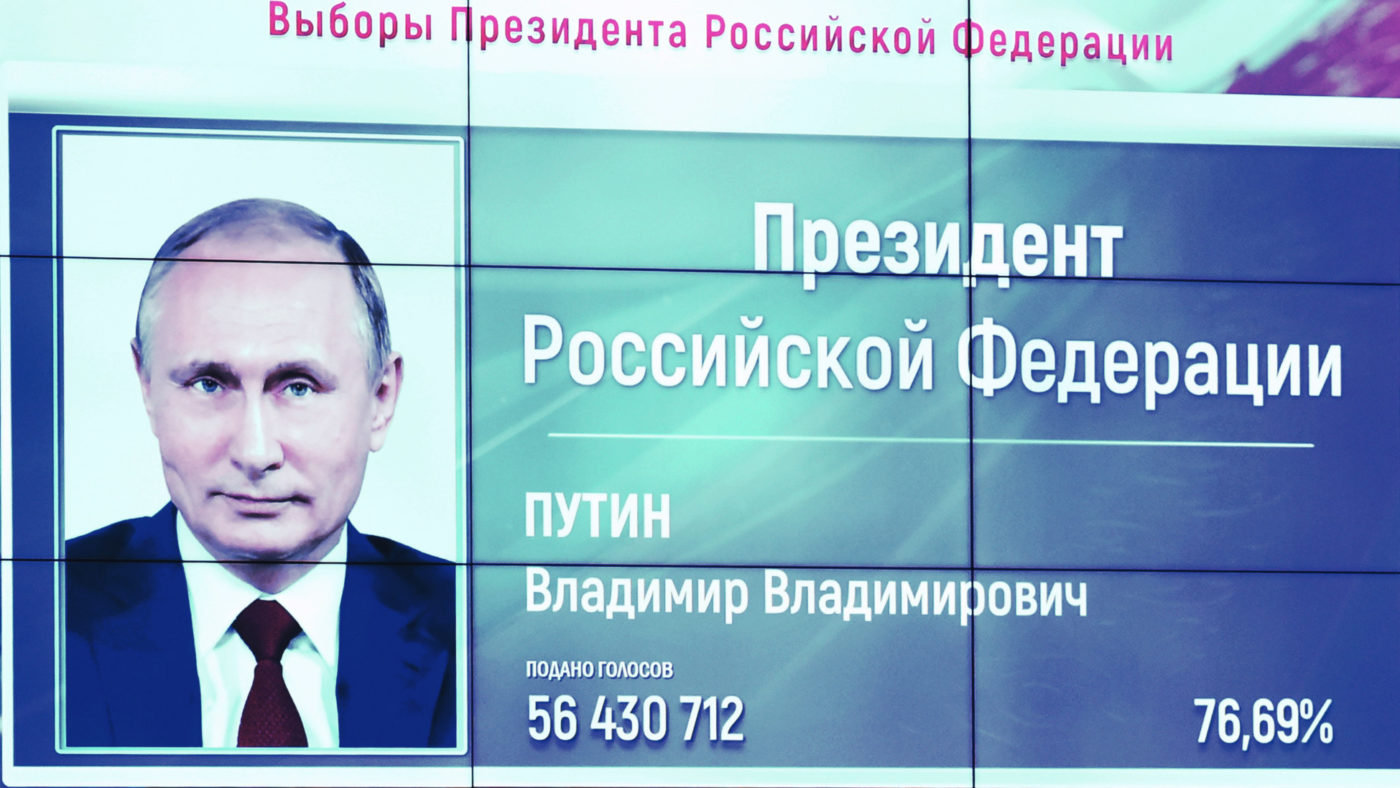

Today the sanctions against Russia – justified by the country’s military aggression towards Ukraine but also other parts of the world – are having a similar effect. A report from the Centre for European Policy Studies explains that “it seems that the ‘unfair’ Western sanctions have had the perverse effect of increasing Putin’s popularity – from the beginning of the Ukraine crisis in November 2013 to the present, his ratings have risen from an ever-low to an ever-high point”.

If one believes in the force of the free market, this shouldn’t come as a surprise. Once an economy is isolated from global trade, the role of the state grows – when Russian firms and people are hindered from trading with the Western world they feel the pressure. Goods that used to be imported are suddenly in short supply, and those who work in exporting firms might lose their jobs. The government steps in to ensure that the immediate crises is handled. The country turns from market freedom towards state intervention, and the people begin to view the rest of the world with suspicion.

Now, the point with the sanctions towards Russia is that they are directed towards the political elite. This does sound reasonable – to punish those directly linked to governments that misbehave rather than ordinary people and companies. The problem is that sanctions in practice work very differently than they do in theory.

A study by Matthieu Crozet and Julian Hinz looked at how sanctions towards Russia are disrupting global trade. Perhaps surprisingly, it is found that only a small share of the trade loss is through those products supposed to be embargoed. The vast majority, 91 per cent of the trade loss, happens through the products that are not part of the sanctions. Why is this? Well, global trade is a complex matter, and happens through advanced business networks. If parts of the networks are hindered by government sanctions, the system as such collapses. Another interesting finding is that the trade loss experienced by Western countries is concentrated in Europe, rather than the US, which is pushing for the sanctions diplomatically. Germany alone bears almost 40 per cent of this loss. While the US has a larger economy than Germany, they bear only 0.6 per cent of the trade loss. The simple reason is that US didn’t have much trade with Russia even before sanctions were introduced.

In a recent study by the European Centre for Policy Studies and Entrepreneurship, we look more closely to the “friendly-fire” effect of sanctions policy. We focus on the two Western economies that are not part of the Russian sanctions are affected by it. One might imagine that the two countries, Switzerland and Israel, would have massively increased their trade with Russia – since Russia is hindered by the sanctions to trade with other Western economies. By studying trade data between 2014 and 2016, we show that the opposite is true. Exports to Russia fell by around 25 per cent in the two sanctioning economies. This is nearly as high as the 30 per cent drop in exports experienced on average by the largest four economies engaged in the sanctions (US, Japan, Germany and UK). Between February 2014 and December 2016, we estimate that Israel had a trade loss with Russia amounting to $680 million, while the loss of Switzerland was fully $2.38 billion.

This teaches us an important lesson. When the global value chains that connect people and businesses together in the modern world economy are disrupted, massive unintended losses are created by third-parties not supposed to be affected by sanctions. Sanctions may be justified in theory, but their cost in practice is much higher than what originally intended.

This observation about global value chains also has security implications. In the long run, countries that are part of the same global value chains are much less likely to enter into wars and conflicts with one another. Sanction policies which, through unintended consequences, exclude Russia from trade with Western economies reduce peaceful interdependence and eventually undermine long-term security.

As the 19th-century economist Otto T. Mallery wrote: “If goods don’t cross borders, soldiers will.” This is, of course, even more relevant in the modern global economy in which global value chains create substantial interdependency between nations. Aggression by states such as Russia needs to have consequences, but the current sanction policies are a problematic approach. For long-term security to flourish, we should include people and businesses in countries such as Russia in the global market, not exclude them. The goal of punishing governments for aggression should be met with different policies.