The UK’s electricity and energy policy is at a critical juncture. EU emissions legislation is leading to the mass closure of coal- and oil-fired power stations; a strategy to replace the loss of reliable electricity generation is urgently needed.

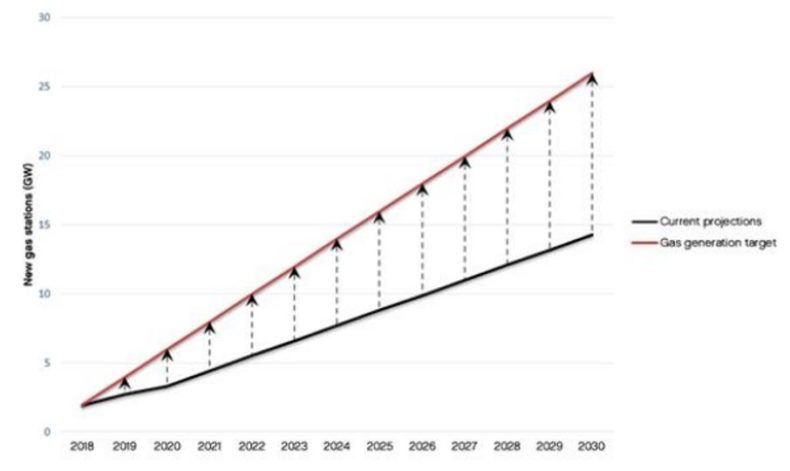

Earlier this decade, the plan set out by the Government was eminently sensible. A roll out of new gas fired power stations was planned across the country. They would deliver 26GW by 2030. However, as Tony Lodge and I outline in our new report, The Hidden Wiring, the Government is some way off meeting this ambition (see figure 1), which will have major implications for the future of our electricity policy.

Figure 1: Shortfall in new gas fired generation vs 2012 ambitions. Gas generation ambition from the Department of Energy and Climate Change; current projections extrapolated from Capacity Market auctions.

While gas-fired power stations should be viable, the growing penetration of renewables on the network is making them uneconomic to run. This is not due to renewables offering better value for money. It is, instead, because gas fired power stations are now required to remain on standby to account for growing intermittency on the network. The Government has introduced the Capacity Mechanism, which should – in theory – incentivise the construction of gas-fired power stations by offering subsidy payments. But it is failing to do so.

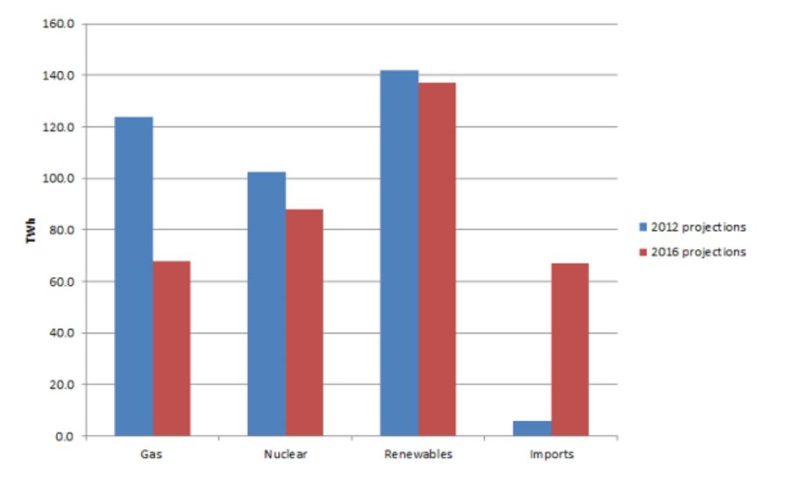

To make up for this, there has been a quiet move towards a new strategy: importing more electricity. The numbers are dramatic. It is now estimated that the UK will be receiving ten times more electricity from overseas in 2030 than was projected in 2012 (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Power generation projections in 2030

Of course, growing the UK’s ability to import and export electricity could be beneficial for electricity consumers. Interconnectors – the infrastructure used to connect the UK’s electricity grid to that of continental Europe – could help deliver secure and cheap supplies right across Europe.

But in Britain’s case, electricity flows are increasingly one-way traffic. In the 12 months to March the UK imported over five times more electricity than it exported. And the UK’s dependence on electricity imports is only set to grow.

There are two key problems with becoming overly dependent on electricity imports. First, this electricity has an unfair competitive advantage over domestic electricity generation as it is not subject to the Carbon Price Floor or network charges. It is estimated that the size of this advantage is around 20 per cent of the baseload electricity price. This therefore artificially suppresses electricity generation in the UK.

The second problem is that many of the electricity markets that the UK plans to import electricity from are expected to have lower reliable supplies going forward. Many coal, oil and nuclear power plants are being phased out in Europe’s main electricity markets. This is likely to be exacerbated by the result of the German elections, with the Greens likely to play a part in the ruling coalition. If the UK continues down the path of growing reliance on electricity imports, this could threaten the UK’s energy security, leaving the country short of electricity – or consumers facing much higher bills.

This should give the Government pause for thought. Now is the time to examine the role that interconnectors play in the UK’s electricity system, and review why the UK’s regulatory environment is failing to incentivise the construction of the gas-fired power stations we need.