In recent decades, the new left has undertaken a rewriting of recent history to systematically misrepresent the classical liberal tradition and suggest that we live in a “neoliberal world order”.

In both academia and the media, wildly inaccurate claims are made. Some even claim that classical liberalism has caused at least as much suffering as the most murderous totalitarian ideologies of the past two centuries.

In fairness, this view is not entirely new. In the 1930s, Western Marxists popularised the idea that fascism was the last phase of capitalist expansion, an authoritarian response of the bourgeoisie to the potential revolutionary outbreak linked to social tensions arising from the cyclical crises of capitalism.

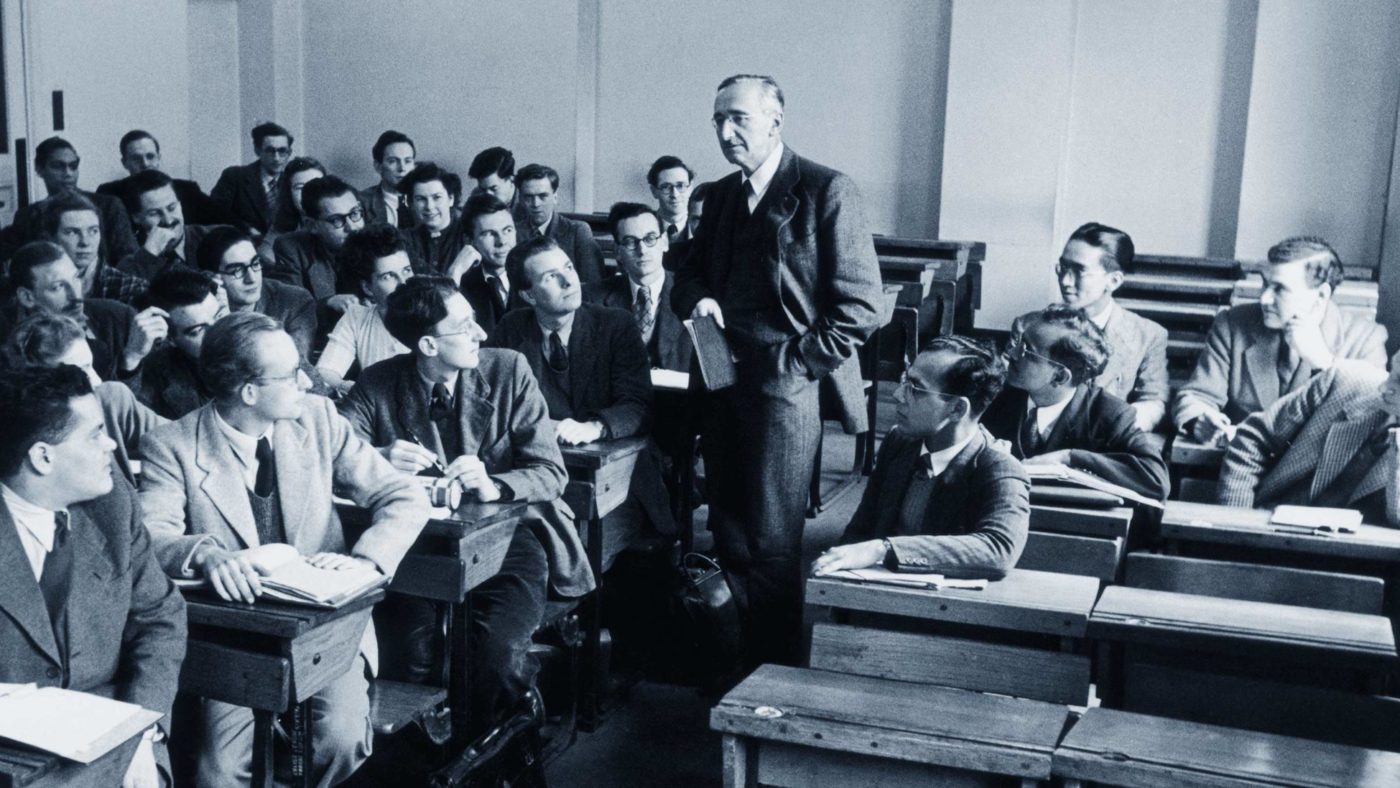

However, it was critical theory, linked to the so-called Frankfurt school, that popularised ideas about how the working classes — theoretically the vanguard of socialist revolution — came to accept capitalist rules.

The new left has followed this trail, with the likes of David Harvey or Owen Jones analysing how the values associated with capitalism and the liberal tradition have been disseminated. In this view, a key facet of inculcating “neoliberalism” is the denigration of the public sector as inefficient, bureaucratic and wasteful and the promotion of the individual at the expensive of the collective.

Similarly, sociologists such as Weber and Simmel link the classical liberal tradition with the culture of work, responsibility and personal merit, while cultural anthropologists claim to have found other, better versions of civilisation where altruism and generosity, not avarice, would be the norm.

The reality is that ideas about the value of work, individual responsibility for one’s own decisions and personal merit as a criterion for the allocation of resources are universal and anthropologically identifiable, not necessarily linked to classical liberal ideas or capitalism itself. These moral principles are referenced in religious texts, including the Bible, and in classical works such as the Ancient Greek poet Hesiod’s Works and Days, written around 700 BC. Classical liberalism, insofar as it places the individual as the fundamental springboard of all political, social and economic discourse, simply accentuates a series of ideas already present in human cultural history.

Just as intriguing as the misguided analyses of classical liberalism is the new left’s obsession with so-called “neoliberalism”.

The term originally referred to a school within the liberal tradition, the so-called ordoliberalism that emerged in Germany after World War II. However, when David Harvey refers to neoliberalism as the dominant ideology in the world, he is not referring so much to the founding fathers of the social market economy as to the economic policies of containing excessive and anti-inflationary public spending. These policies are themselves linked to the Chicago School and Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, both of which exerted a major intellectual influence on the policies implemented in the wake of the 1970s oil crisis.

Neoliberalism is to the radical left what patriarchy is to feminism: a purely discursive antagonism. The reality is that far from being “neoliberal” in any meaningful sense, Western democracies combine liberal elements with obviously social democratic ones, such as so-called social rights and welfare states. Even in countries with conservative governments, the policy mix is very far from the laissez-faire libertarian free-for-all some leftwingers would have you believe.

Indeed, with public sector spending taking up a considerable chunk of Western countries’ GDP, one could just as well argue that the “big government” model is in the ascendancy. Even after years of supposedly crushing austerity, overall public spending in the UK remains at 41 per cent of GDP, for instance — hardly a wholesale retreat of the state.

In general, the gap between social liberals and classical liberals lies fundamentally in the consideration of power. For social liberals, the power that threatens freedom is not only political power, other forms of power (social, economic and so on) can also put their views at risk.

On the other hand, for the classical liberals, institutional power is the main threat. Unlike left-wing thinking which sees no essential contradiction between power and freedom, in liberal thinking, there is always a mistrust, a distrust of power.

Whether or not one you consider yourself a classical liberal, to dismiss it as simply a justification of selfishness is a woefully inadequate misreading of an important, influential school of thought.