The United Kingdom is, in truth, a bit of a misnomer. As CapX has outlined in its excellent Rebalancing Britain series the country remains deeply divided in terms of economic prosperity.

Boris Johnson has committed addressing such disparities – declaring his ambition to ‘level up’ all parts of the nation in his first speech as Prime Minister.

It is in this context that the Centre for Policy Studies this week published a report into economic imbalance in the UK and what to do about it.

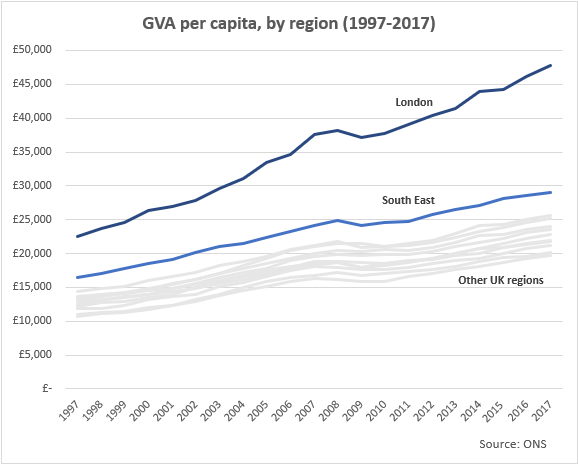

We begin with a snapshot of just how unevenly the economy performs across the regions of the UK. Gross Value Added (GVA) statistics are a robust indicator of economic performance, and reliable data has been collected them on a regional per capita basis over the past two decades.

As the graph below makes clear, London stands head and shoulders above other regions on this metric. Moreover, our analysis found that the capital’s GVA per capita grew the fastest over this time frame – while other regions’ increased by 80% on average, London’s did so by 111%.

And while of course we should celebrate the capital’s success, our report is focused on working out how other regions can enjoy that same level of prosperity.

One of the most powerful tools to help struggling areas is devolving political power. While successive governments have taken steps to hand power back to the regions, we believe that process should be extended, both geographically to take in new areas, and in terms of the powers those places have.

As a starting point, all combined authorities – like in the West Midlands or Greater Manchester – should be able to enjoy the powers and responsibilities currently available to the Mayor of London. Devolution in the capital since the creation of the Greater London Authority in 2000 has given City Hall more control in areas such as transport and planning, with huge economic benefits as a result.

It has also created a strong feedback mechanism, in which politicians are more obviously incentivised to facilitate economic success. Lack of skin in the game leads to all sorts of shortcomings in politics, but if a local mayor knows their future career depends on sorting out a congested transport system, they have a lot more reason to get things right.

Beyond that, we believe that the government needs to show more ambition in devolving other competencies which it has largely retained in Whitehall. Fiscal devolution, for instance, is particularly limited – as the chart below shows, the UK is now one of the most centralised countries for tax take in the developed world, with just 5% of tax raised at a local level.

In our report, we are deliberately non-prescriptive about how a more devolved tax system should operate. Indeed, this is precisely the point of devolution – the idea that local authorities are best placed to decide how to run their area. That said, likely candidates for devolution would include property taxes like stamp duty and business rates, as well as granting more powers to local authorities over how council tax is administered.

Understandably, some may worry that greater flexibility in the tax system could trigger a ‘race to the bottom’, leaving local authorities thinly stretched and under-resourced. But these fears are probably misplaced. Indeed, an extensive OECD paper on tax competition which we cite in our report found little evidence – especially in wealthier nations – that this typically occurs when countries permit such fiscal devolution.

Moreover, even if devolution of various taxes did lead to headline rates going down, that would not necessarily be a bad thing. In everyday life, we have premium and budget versions of supermarkets, clothing retailers, and transport options, with people given the choice of spending a little or a lot depending on what they want. Why should the council they choose to live under be any different?

Allowing people this choice would give local governments to get a better idea what ratepayers want from them, and how much they are willing to pay for the privilege.

Important as devolution is, we recognise that it cannot level up Britain alone. To that end, we suggest a suite of other measures, ranging from the creation of a National Infrastructure Fund to the establishment of a new wave of Opportunity Zones – where companies in deprived areas can benefit from more sympathetic fiscal rules and business regulations.

Taken together, we believe our proposals can match the positive rhetoric of the new government in terms of wanting to level up Britain, and help to unleash the dormant prosperity in those areas which need help the most.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.