As the IMF and World Bank prepare for their virtual spring meetings, the economic impact of COVID-19 on developing countries is the dominant issue. It is important that the world’s rich countries come together with a Marshall-type plan to help these countries, many in Africa, to kickstart their recoveries.

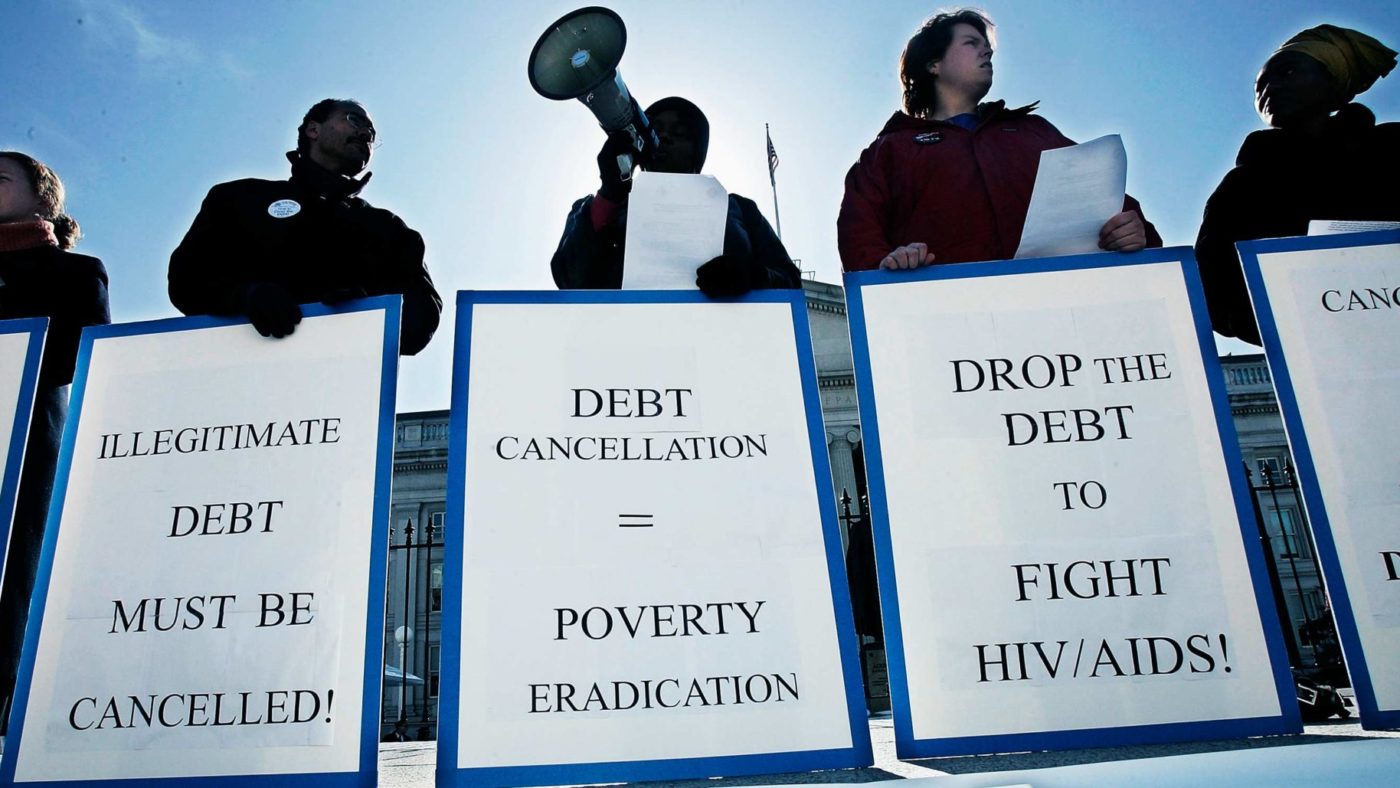

The Jubilee Debt Relief campaign, which consists of a number of UK based charities, recently wrote to world leaders to ask for African debt to be cancelled altogether. Some others have suggested a debt moratorium.

However, how to help developing countries with this crisis is a separate issue to the campaign for debt relief, and it would be wrong to conflate them. The first is an essential measure, indeed a moral imperative. The second is a political and economic decision, which requires weighing numerous variables.

Why do investors buy emerging market debt? Largely because they are making a bet on developing country returns, and that the future growth potential is secured on improved governance and reform in the particular country. In other words, things will get better if proper governance and structural and regulatory reform occurs.

This has a very important disciplining effect on governments. Reforms are difficult, and in developing countries they are even more challenging than in developed ones. Rent-seeking oligarchic elites make undertaking reforms extraordinarily difficult. Meanwhile, immature democracies are often manipulated by populist politicians peddling short-term pleasure that inevitably brings a nasty hangover of inflation, currency crisis and economic crash. The discipline of loan conditionality, or the presence of a debt that has to be serviced is actually an ally for governments who seriously want to reform.

The events following the Paris Club’s forgiveness of debts of Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) prove this hypothesis. As noted by Euromoney: “African sovereigns loaded up on cheap international debt after the heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC) initiative granted debt relief to 33 African countries, but many did not make the corresponding adjustment in fiscal discipline.”

A cancellation or moratorium on debt now will simply cause another bigger problem later on and will deprive emerging market countries of future private sector investments and loans. Given that developed countries themselves will increase their own debt levels in an unprecedented and untested fashion to cope with the pandemic, there will be much less availability of capital for developing countries unless private sector funds can do much more of the heavy lifting. Attracting private capital will be much more dependent on actual reform.

The approach to debt relief must also be applied on a case-by-case basis. No two sovereigns are the same: treating all countries, or even a continent such as Africa, as homogenous, with a one-size-fits-all approach will lead to poor outcomes for everyone.

The IMF Article IV Surveillance reports and the WTO trade policy reviews of countries indicate where major structural reforms are still needed. Take for example Africa’s largest economy, Nigeria. Their debt to GDP ratio is 28%, half of most other sub-Saharan African countries. This is sustainable. According to the [IMF], the real issue is “persistent structural and policy challenges continue to constrain growth”. Clearly it is correcting those structural issues, rather than unconditional debt relief, that is the key to solving Nigeria’s long-term economic problems.

While it is very important to help developing countries deal with both the virus and its aftermath, we should not conflate that process with the wholly separate issue of their debt. Even if some sort of pause or relief from debt repayments is required, it must be subject to significant conditionality that ensures that we do not simply repeat the mistakes made by the Paris Club.

That conditionality must focus on adopting the reform recommendations proposed by the IMF and the other Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and must take into account the findings of the WTO trade policy reviews.

Transparency is also key. Noted debt relief expert Anna Gelpern, of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, has said that debt transparency should be a “particular priority”. That should include full disclosure by sovereigns, including of outstanding undeclared debt (e.g. – related to China) and contingent liabilities such as arbitration judgments. The IMF and World Bank have recently highlighted the importance of contingent liabilities, which can have a profound impact on a country’s economy and risk perception. International lending institutions, and other investors, must have full transparency when it comes to these debts and liabilities.

The upshot of all of this is that if we really care about the poorest in poor countries, we must look beyond the temptation to seek easy solutions. Instead, we must recognise that the business of reform is hard work and requires tremendous discipline. Conditionality is one of many tools that can be used to secure reform in order not to repeat the mistakes of the past.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.