The basic problem with today’s world isn’t the fires, it’s the lack of firemen. The problems faced by the West —dealing with a rising China, containing a dangerous but declining Russia, thwarting Iran’s over-grand Mideast ambitions, safeguarding global prosperity—are not historically that out of the ordinary. Instead, the increase in today’s political risk is the result of the lack of a coherent ordering power – made up of actors motivated by their common interests – to deal with these global foreign policy challenges.

Indeed, the overlooked historical headline of our time is the decline of the West and the rise of the rest. The shock elevation of Donald Trump, the Brexit vote, and Europe’s endless crises are all symptoms of this same phenomenon. The old world order that has run things since 1945 has neither the power or the will to continue to do so on its own. We are entering a new era of many powers. ‘The rise of China’ is merely short-hand for the relative rise of the rest of the Emerging Market world, from India to Brazil, and the diffusion of global power away from the US and especially Europe.

The key to this strange new era is to understand the nature of the global order we now live in, and how stable that world is. The fancy international relations term for this is Waltzian systemic analysis. However, it is far better (and infinitely more fun) to look at the surprise break-up of the Beatles and the even more shocking longevity of the Rolling Stones for clues as to why some systems dramatically fall apart, while others evolve and remain.

The Beatles Disintegrate, The Stones Re-Group

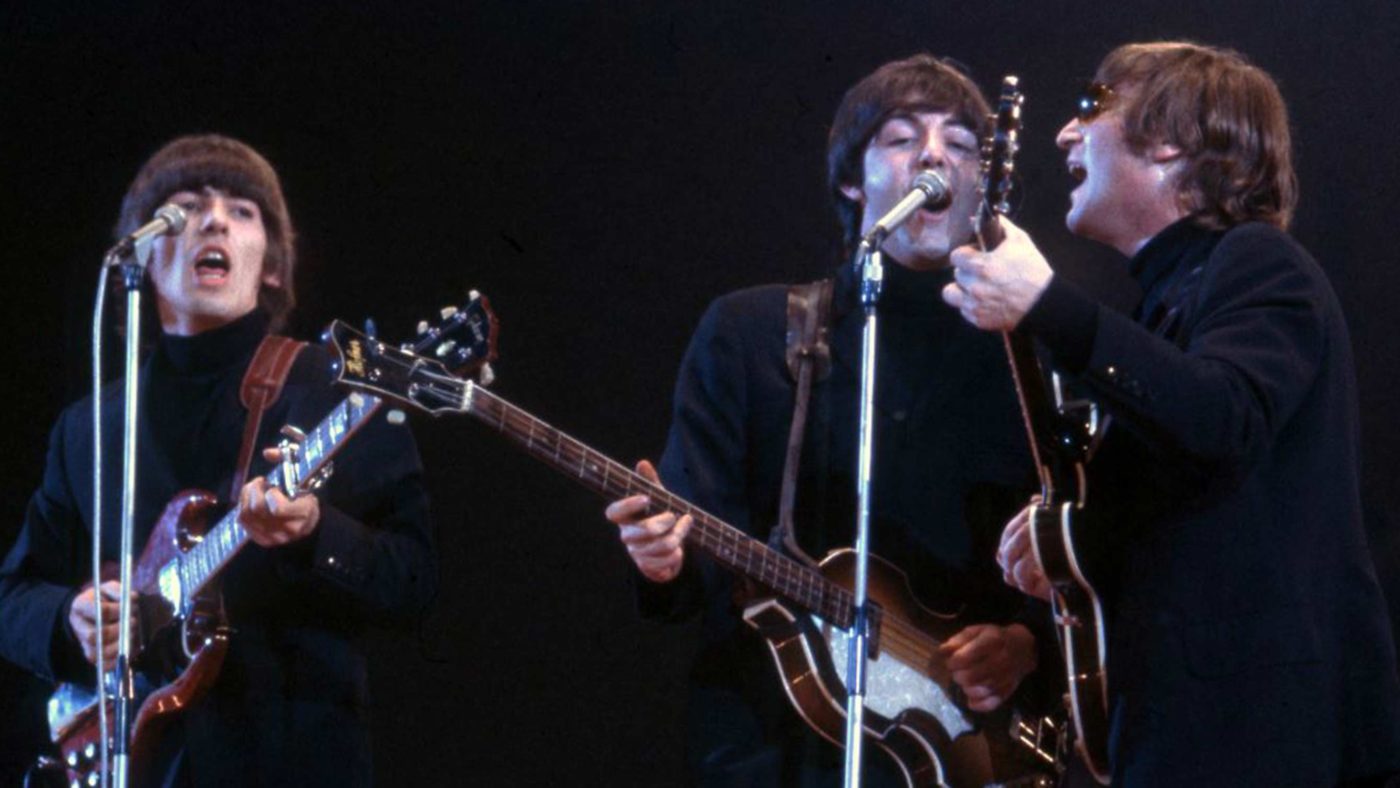

In the mid-1960s absolutely no one would have bet the Beatles would be outlived by the Stones. The Beatles worked on the basis of a stable bipolar order (Lennon-McCartney dominance) whereas the Stones were in the midst of a chaotic shift from a unipolar to a multipolar and eventually a bipolar-driven order. Yet fast forward to Glastonbury in 2013 and the Stones were still playing 43 years after their friendly rivals had broken up.

The Beatles fell apart in the blink of an historical eye, straying from mid-60s stability all too quickly. A primary reason was that the (to that point) dominant John Lennon and Paul McCartney did not make room for the increasing talents of George Harrison.

On Rubber Soul (1965) there were 11 Lennon-McCartney originals, two Harrison songs, with only one by loveable drummer Ringo Starr. On 1966’s Revolver, there were again 11 by John and Paul, three tunes by George, and none for Ringo. Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) was in many ways the apotheosis of Lennon-McCartney dominance, with 12 songs by John and Paul, only one Harrison tune, and none for Ringo.

But by now Harrison, an increasingly gifted guitarist, singer, and songwriter, came to resent his subordinate status, as John and Paul, like so many ordering powers, proved resistant to change a system that had for so long favoured them.

But as the Beatles ties frayed, the Rolling Stones surprisingly regrouped. Originally the Stones were a unipolar world, dominated by the talented, troubled Brian Jones. As bassist Bill Wyman put it: Brian ‘formed the band, chose the members, named the band, chose the music’ and served as their first manager.

But Brian quickly declined, as singer Mick Jagger and guitarist Keith Richards inexorably rose. First, Brian’s position in the group eroded as the Stones hired Andrew Loog Oldham as their manager, who increasingly turned the spotlight on Mick as Rock’s best front man.

Second, Mick and Keith wrote the songs which made them the vital creative power in the group. Third, Brian’s worsening drug problems meant increasingly he couldn’t play, live or on albums. Fourth, Jones lost his then-girlfriend, the sexy, dangerous Anita Pallenburg to Richards, symbolically illustrating the changing the of the guard.

Unsentimentally thrown out of band in June 1969, Brian drowned in mysterious circumstances later that year. Brian’s death, though undoubtedly tragic, directly lead to the Stone’s stability and unsurpassed longevity, as with his passing the group settled into the creative Jagger-Richards power duopoly which accurately mirrored the organic creative power distribution in the group.

Through the Looking Glass with the Walrus

Now let’s take our Beatles analogy a step further, as the band’s demise eerily mimics the collapse of today’s West as the global ordering power. A distracted John is Europe, haunted by his own personal demons and problems, he has lost interest in running the band, even as the continent has largely lost interest in what is going on in the rest of the wider world.

A frustrated Paul (after manager Brian Epstein’s drug overdose death in August 1967) is the US: running things, but with less and less help; resented by the others for taking charge, even as he resents their leaving him to shoulder more and more of the burden on his own.

George is today’s China and other emerging powers: if his growing abilities are not recognised, he is increasingly prepared to go his own way, setting up institutions he – and not the out of date power order – controls. Ringo signifies everybody else, all the world’s smaller powers, who must gamely work with everyone whatever the power system.

The White Album (1968) was the group’s response to these power tensions, and is suggestive of where our world is today, with its eroding system of order. As John later shrewdly remarked, there is no Beatles music on it at all, just John, Paul, and George, each with a backing band. Every great power simply going its own way sums up the world as we find it today, with the old institutions that buttressed the pos-1945 order – such as the WTO and World Bank – increasingly sidelined. The danger in this is that, as the Beatles found out, it leads to bloated chaos.

Let It Be (1970) amounted to the stunning collapse of the group in all but name, with an uncaring John and George limping through the joyless record, harassed by an increasingly exasperated Paul. The group’s last flicker ironically came with their finale, Abbey Road, when George (with ‘Something’, and ‘Here Comes the Sun’) at last got the credit he had long deserved. But it was over. The world had changed. The creative constellation in the band had changed. But the power dynamic had not. This is the classic definition of a failing system and it is where the West is headed today.

Getting the Band Back Together

But as the Rolling Stones’ miraculous longevity illustrates, nothing is inevitable. In policy terms, the West must adopt a three-pronged strategy to avoid the Beatles’ fate. First, George must be re-engaged. The US, UK, and Europe must reach out to the many emerging democratic powers, such as India, South Africa, Brazil, Mexico and Ethiopia, as well as older, established democratic powers such as Japan, Israel, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, making them stakeholders in our new era by giving them a greater say in global governance where possible.

For example, a reinvigorated Quad in Asia—with Australia, Japan, India, and the US as charter members–ought to be expanded, leading the way to manage and contain the rise of undemocratic rival China.

Second, John and Paul must find a way to keep working together; in this case, the US, UK, and Europe must utilise the establishment of this nascent global democratic alliance as the new glue that binds.

Third, this new West-plus global order must see to it that other disruptive powers do not overturn this new ordering constellation. Rising China must be both engaged and hedged against; dangerous, disruptive Russia contained; and revolutionary groups like ISIS utterly destroyed.

For in the end, the West will either evolve and survive as an ordering power as the Stones have done, or remain inflexible and come apart like the Beatles. Everything is to play for.

If the new ordering powers broadly reflect the present power distribution in the world now (as opposed to that of 1945) the chances for stability rise exponentially. The only way for the US to make this happen is to construct a durable alliance system that helps America order the world for the foreseeable future. They must, in other words, learn to get by with a little help from their friends.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.