Bonn Is Not Weimar was the title of a 1956 book by the Swiss journalist Fritz René Allemann. He argued that the (West) German Federal Republic, founded in 1949 and with Bonn as its capital, had devised a stable form of parliamentary government which had successfully avoided the political chaos and weak, short-lasting coalitions of the Weimar Republic.

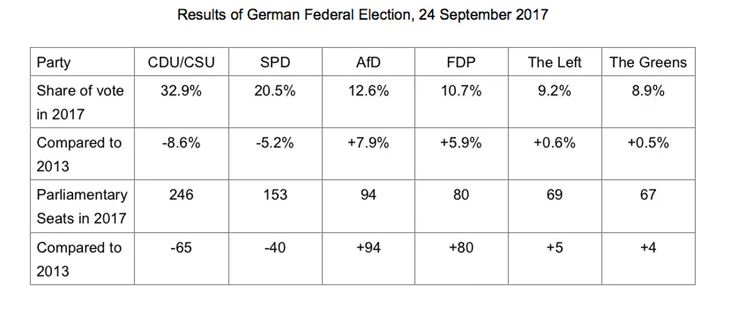

The recent federal elections, held in September 2017, appear to have marked an abrupt end to that stability. A total of six parties (seven if we include Angela Merkel’s Bavarian ally, the CSU) are now represented in the Bundestag or federal parliament. That’s the largest number since it was decided in 1952 that every party needed to win a minimum of five per cent of the overall vote to secure a place in parliament.

The two major parties, Merkel’s conservative Christian Democrats (CDU) and the centre-left Social Democrats (SPD), both lost support, while in another post-war first, an extreme right-wing party, the anti-immigrant Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), entered the Bundestag with 12.6 per cent of the vote and 94 seats.

The SPD initially refused to continue as Merkel’s junior partner in a grand coalition, instead expressing a desire to go into opposition. The CDU/CSU was therefore obliged to look elsewhere – to the Greens and the pro-business Free Democrats (FDP) – to form a coalition. But that plan failed when the FDP walked out of talks on November 19.

Just three alternatives now present themselves. The first is to stage fresh elections. However, this could easily end in another indecisive result and even further gains for the AfD. The second is to form a new grand coalition. SPD leader Martin Schulz showed some signs of moving in this direction by engaging in preliminary talks with the CDU and CSU but no deal has yet been struck.

Finally, the SPD could decide to “tolerate” a minority CDU/CSU administration. It would not formally join the federal government and would reserve the right to oppose its overall programme and present alternative policies, but would be open to approving (or rather not blocking) parliamentary legislation on a case-by-case basis in order to prevent complete political paralysis.

The risks they face

All of these options present significant risks for the SPD. As the oldest party in Germany (it was founded in 1875), and one that experienced several dramatic splits and changes of direction in the 20th century, it arguably has most to lose from the recent fragmentation of party politics. This is because it risks haemorrhaging votes both to its main socialist rival, the Left, and to the populist, anti-system right.

It has been widely accepted that the SPD’s historically poor election result was punishment from voters for its coalition years. In large parts of eastern Germany it is now in fourth position, behind the CDU, the AfD and the Left. All this makes it even harder for the party to forge ahead nationally to beat the CDU/CSU at the next federal election while maintaining a position inside the governing coalition.

It’s also worth noting that if the SPD did agree to another grand coalition, the far-right AfD would become the largest opposition party in parliament.

But accepting a minority CDU/CSU administration comes with all the same risks as a grand coalition without any of the advantages of government. The last time the SPD tolerated a right-wing government was between 1930 and 1932. Back then, the minority administration led by the conservative Catholic politician Heinrich Brüning instituted a series of highly unpopular welfare and public spending cuts in response to the economic crisis, aided at crucial moments by the SPD’s decision to “tolerate” such measures without being able to negotiate any significant concessions in return. In the two Reichstag elections of 1932, the SPD’s share of the vote crashed to 21.6 per cent in July and 20.4 per cent in November.

Even if we accept that the SPD had no alternative but to “tolerate” Brüning in the early 1930s, the situation today is very different. Germany is not facing an economic downturn, let alone a crisis on the scale of the Great Depression. A grand coalition would rest on a clear majority in the Bundestag, offering – in contrast to the late Weimar period – a realistic chance of the government lasting for a full four years.

![]() Unlike Brüning, Merkel favours consensus. The SPD has a significant opportunity to obtain concessions on key issues affecting its members and supporters, including the environment, welfare and immigration. In the coming weeks, the SPD should grasp the nettle and aim for a formal coalition agreement, rather than “tolerating” a minority CDU-led government.

Unlike Brüning, Merkel favours consensus. The SPD has a significant opportunity to obtain concessions on key issues affecting its members and supporters, including the environment, welfare and immigration. In the coming weeks, the SPD should grasp the nettle and aim for a formal coalition agreement, rather than “tolerating” a minority CDU-led government.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.