Edmund de Waal, a celebrated potter and ceramicist who had one of the literary hits of 2010 with his biographical memoir The Hare with Amber Eyes has now written a study of the remarkable history and nature of porcelain. De Waal has devoted much of his working life to porcelain, and this is not a mere history of the white ceramic that helped shape the wealth of nations from its discovery in China more than two thousand years ago. It is an attempt to capture the inner nature of porcelain, its power to mesmerise and to bankrupt its addicts.

Porcelain was revolutionary. The relative economic and technological power of the East versus the West can be traced in the history of this eerily white and inexplicably strong and delicate ware. Whiteness was a powerful idea in pre-industrial times. It suggested a path out of a world that was much darker than ours – a world before clear glass and clean water, before artificial light and bleached food.

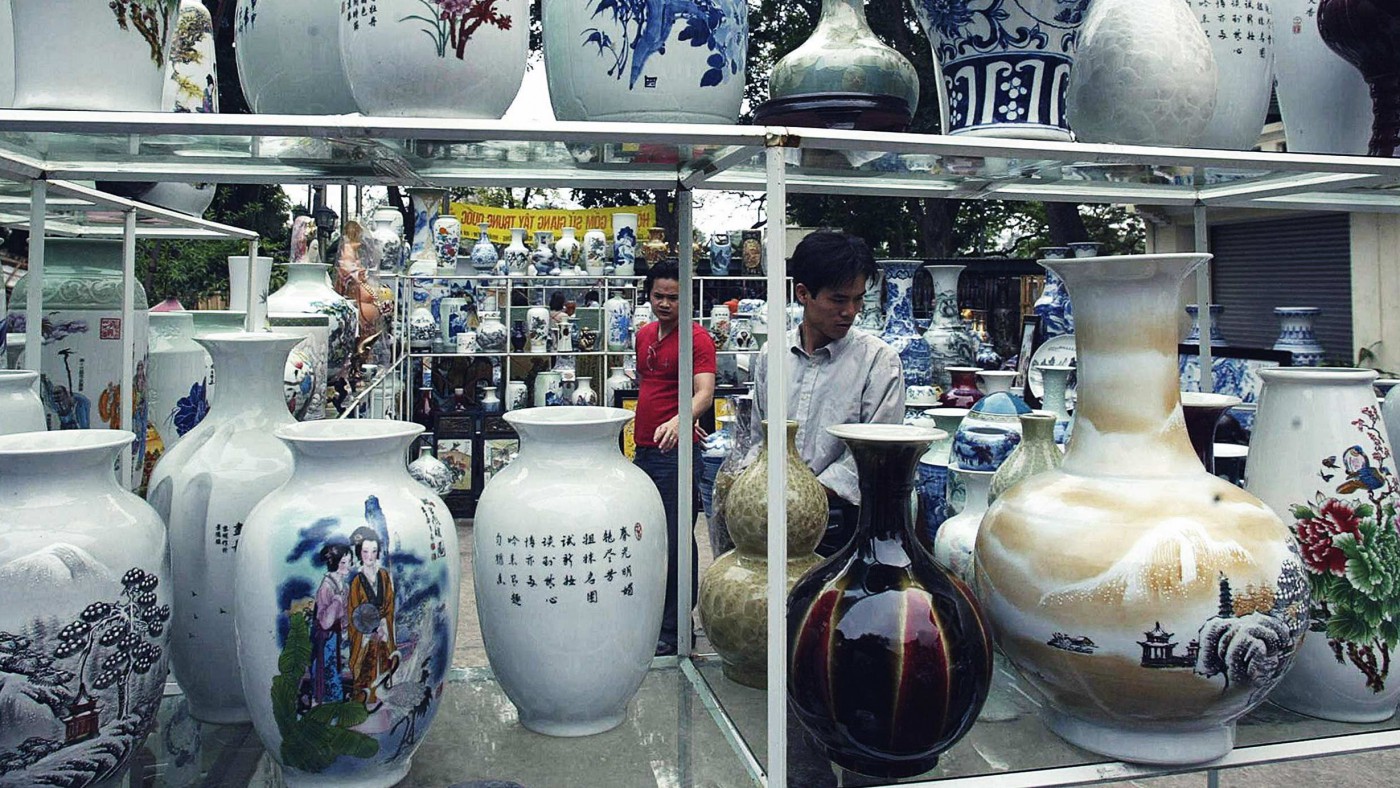

Yet the first true porcelains from the Han Dynasty which ruled for four centuries from about 200 BC were not glazed anything like white, but might be red, or green, or gilded, or the subtle grey-green called celadon. These are pieces that are greatly prized today, but it was the later white porcelain decorated with the deep cold colour of cobalt (black when painted on the clay, but running blue in the firing) that first captured the attention of the wider world. This is the porcelain that came to be called, simply, ‘china’. These were the Ming Dynasty bowls and vases and cups that defined porcelain in the Western mind. They were nothing like the earthenware and stoneware ceramics made in the Middle East or in Europe, for the very good reason that no one outside China knew what they were made of, or how to make them.

For this reason porcelain became the greatest trade secret of the age, the killer app, the intellectual property goldmine of the 14th century onwards. The grand halls and private chambers of emperors and kings were filled with Ming ware, and although there were repeated attempts to reproduce the Chinese porcelain technology they were serially unsuccessful. Part of the Chinese advantage was that true porcelain was unmistakeable. A porcelain piece rang when struck, like a musical instrument. Whether glazed or not it was uniquely hard – no blade would mark it. Some porcelain bowls were capable of boiling water, like an iron pot (in fact It could withstand extreme “thermal shock” – a porcelain ceramic when taken white hot from the kiln could be dropped in iced water and survive fully intact). It was translucent, like the thinnest paper. Even unglazed it was waterproof.

Whoever understood this technology could command wealth without limit. It was no accident that the early European pioneers of porcelain-like wares were equally interested in trying to turn lead into gold. Johann Böttger in Dresden was the first European to create a porcelain that could match the Chinese ware, and Böttger was a charismatic naive whose main interest was alchemy but who happened to stumble onto the secret of porcelain. The first European porcelains were “soft paste” – they did not have the unearthly hardness of the Chinese ceramics – but they were good enough to feed the limitless desire for white things, the Porzellankrankheit or porcelain sickness, a condition suffered by the rich and powerful. The only symptom of porcelain sickness was the desire for more and more porcelain, and then more. Böttger’s patron Augustus the Elector of Saxony (“Augustus The Strong”) began with 16 pieces of Chinese Ming ware, moved on to Japanese Kakiemon with its warm whites and red and yellow glaze decorations, and ended – once the secret of its manufacture had been broken – with porcelain from his own factories in Dresden and Meissen. By the time of his death he owned 35,798 pieces of porcelain, the largest collection in the West.

The composition of porcelain is complex but not difficult to understand. All ceramics are based on a mixture of two sorts of minerals, the refractory elements that do not melt or deform in great heat, and the vitreous elements that fuse like glass. The glaze that finishes most porcelains in a second firing is almost pure vitreous material. The mystery of porcelain was the mystery of the two clays, the refractory and the vitreous, plus the technique of firing at very high temperatures.

The clays were kaolin and the white soapstone that the Chinese called petunse. They were first found in Jingdezhen in China, which became the world’s city of porcelain – a Detroit or Silicon Valley of its time – and the biggest source of China ware for centuries. But in fact the clays can also be found all over the world. In the early 18th century a Bristol apothecary called William Cookworthy realised that comparable clays were abundant in Cornwall, although it required the ruthless business skills of Josiah Wedgwood to make the Cornish clays profitable. By the late 18th century there were porcelain factories throughout Britain – in London’s Bow and Chelsea, in Lowestoft, in Bristol, in Stoke-on-Trent – and the Chinese industry had lost what a management consultant would call its ‘core competence’.

The diffusion of porcelain technology out of China is like modern economic history in reverse. The Chinese held the most powerful industrial secret ever discovered, and profited immensely. It was not the only Chinese trade secret – even before the end of the 14th century the Chinese had invented paper, moveable type, gunpowder, lacquer, advanced clocks and synthetic pharmaceuticals – but porcelain proved the most potent. But trade erodes intellectual property, as western companies are finding in China today. Gradually the Chinese technology was unpicked, until Europe and then the Americas were producing more porcelain than China. When President Richard Nixon visited Chairman Mao in 1972, the gift he brought to Beijing was a porcelain sculpture of swans, made by the Boehm Porcelain Company of Trenton, New Jersey.

Edmund de Waal is a potter who works at the wheel, “throwing” circular forms. Throwing has fallen somewhat out of fashion in ceramic work today (the preference is for sculpted, “built” pieces, often drawing on Japanese raku styles), but it is an ancient part of the craft. There is something devotional about the act of throwing. The clay is centred (an art in itself), and then as the wheel turns it is drawn out, and then up. Sometimes the clay responds. Sometimes, for no apparent reason, and even in the hands of an experienced potter, the engineering fails, the pot falls in on itself, and it is necessary to start again. If it does work, then the half-dry clay must later be worked again, the excess materials trimmed back and smoothed. Potting is time, and work, and furious concentration on a goal.

The White Road reads like an unfinished studio project. It is a scrapbook of notes and reports of journeys through the world of porcelain, to Jingdezhen, to the West Country, to Japan, to the Cherokee country of America, and to Dachau where the Nazis established a völkisch porcelain factory. De Waal has not decided exactly what story he wants to tell so the reader gets everything, including a lot of shard-like two-word sentences that should really have been thrown away. It is not even necessary to read between the lines to tell that de Waal is a man with a lot of projects on the go, and The White Road is only one of his itineraries. It is true that pottery is peculiarly difficult to write about – it falls into a literary zone where prose is more likely to run purple than white. Yet it can be done: de Waal’s previous book was made of well-turned and properly-trimmed paragraphs, all to the purpose. If The White Road were a clay pot, the studio master would surely break it and tell the student to begin again.

The White Road: a pilgrimage of sorts. Edmund de Waal, Chatto & Windus, RPR £20.