The Resolution Foundation wants to cap ISAs (investment savings accounts), the UK’s tax-protected savings and investment accounts. You pay into an ISA with your post-tax income, and can either invest within it or just get interest on cash savings. Any interest, capital gains or dividends you receive within the ISA are not taxed.

Today you can contribute up to £20,000 a year, and besides that there’s no cap on how large it can get from those deposits and the growth you might hope for from investments. The Resolution Foundation wants to cap the size of the pots at £100,000, whether from investment growth, or from contributions, above which any extra money would be taxed as normal. I think its analysis is short-sighted and forgets the second-order effects that savings and investment have on the rest of the economy.

For investments held outside of ISAs, investments in the UK are taxed very heavily. For higher and additional rate taxpayers, dividends are taxed at 33.75% and 39.35% respectively. Capital gains – increases in the value of your shares – are taxed at 20%.

Over the course of, say, a 30-year investment period, this tax can make an enormous difference to the size of your returns: £296,000 invested for 30 years at a 5% real return, with the returns re-invested over that time, will earn about £1,026,452. But if you impose a tax of 33.75%, you get 3.3125%, and your return will be £502,504 – before capital gains tax. Impose the additional rate tax and you’ll make £438,332.

Dividends – distributed profits – have also already been corporation taxed at 25%, which means £100 of profit returns between £49.69 or £45.49 of dividends after both taxes – an effective tax rate of between 50.31% and 54.51% compared to returns from assets that are not taxed by either corporation tax or dividends tax.

I chose £296,000 for a reason: it is the price of the average UK house. Unfortunately, because housing supply is constrained, houses are an investment too, even for people who only own the house they live in. For most people, their house is the biggest savings vehicle they own, and they hope to either be able to draw on some of its value in retirement via equity release, or leave the house to their children to inherit.

The UK raises relatively high levels of money from property taxes compared to other countries, but the system is extremely favourable to certain forms of home ownership-as-investment. You don’t pay capital gains tax on any value uplift on your own home, and the “return” you get from your investment – the free rent, the pleasure of living in a nicer house, the benefits of accessing a better school nearby, etc – is taxed very leniently.

There’s council tax, but that’s specifically designed not to increase in line with rising house prices – it’s pegged to what a house was worth in 1991, or what a newly built house would have been worth if it had been built in 1991. The total amount raised from council tax is about £42bn, on £8.4 trillion of residential property wealth. Average rental yields are 3.7% in the UK, so that’s £310bn of rental values – so council tax is only about an average 12% tax on the annual “return” from owning, whereas income from any other investment source is taxed at 50%+.

Then there’s stamp duty, which is a terrible tax, but because it falls much more on people who move houses a lot, since it is only paid when you sell (which penalises people for moving for, eg, better jobs or to have more children). It’s not really a tax on investment at all, but rather a tax on transactions – a family that sits in a gigantic mansion for forty years will end up paying much less than one that has to move between much less valuable ones every couple of years for work or other reasons.

So housing in the UK receives extremely favourable tax treatment compared to other investments, and increases in the value of houses have been almost entirely shielded from tax. The aggregate value of UK housing has risen by +75% (£3.6 trillion) over the past decade, little of which will be caught by capital gains tax.

It’s hardly a surprise that the UK’s savings rate is low, when this does not include house “savings”. Nor is it a surprise that people with mortgages don’t have much left over for cash savings or equities investments.

Besides pensions, which aren’t accessible until retirement, ISAs are the only “safe harbour” for savings that receive anything like the same tax treatment as housing.

What the Resolution Foundation is proposing is to curb this safe harbour dramatically – so that housing is left as pretty much the only way you can save money in the UK without facing a large tax penalty for doing so. The consequence would be to shift even more money into “housing as an investment”, inflating the cost of UK housing even more, exposing more people to the risk of being invested in a single asset, and of course making it harder for future governments to let the cost of housing actually… fall.

That’s very bad. It goes in precisely the wrong direction: as well as making it harder for governments to let house prices fall, it makes it harder for them to reform the taxation of housing and property so that it is less advantaged compared to other investments. This is, in fact, something that Resolution has written about previously, so it’s surprising that they would now propose something that would make that task – far more important, by anyone’s measure – even harder than it already is.

The big windfall Resolution sees coming that it wants to tax is higher interest rates leading to higher returns for cash ISAs. But interest rates are only higher because inflation is so high, and in real terms interest rates are still rock-bottom – cash savers are still losing out in real terms, and higher interest rates are just blunting some of the damage from inflation. It seems muddled to treat higher nominal interest rates as a windfall that will “significantly boost savings returns” when it’s in the context of double-digit inflation numbers.

The £100,000 cap is really low, and the proposal comes after pages and pages outlining just how low the UK’s savings rate is. It seems backwards to spend a report complaining that we don’t save much, and then conclude that we could cap people’s tax-free savings at this very low level because so few people have savings this high!

To put the £100,000 cap in perspective, if you saved £300 every month and made a 5% annual real return, in eighteen years you’d hit the cap. If you saved £500 every month, you’d reach it after twelve years. To say that this is the limit of the savings we should be encouraging people to do seems very strange at the end of a report bemoaning the country’s low existing savings rates. And these estimates assume that the cap would rise in line with inflation. If it doesn’t – and, come on, it probably wouldn’t – the cap will get lower and lower in real terms over time.

The purpose of these proposals is to raise money to subsidise poorer people’s savings, but you don’t have to pair every proposal for higher spending with a very-closely-related proposal for higher taxes – taxes can come from anywhere, and it seems unlikely that the optimal way of raising new funds to subsidise some people’s savings is to penalise other people’s rather than, idk, taxing carbon or something. I strongly doubt that, if you put a gun to the Resolution Foundation’s heads and asked them to name the least-bad way to raise an extra billion quid, even they would say this was the best way of doing it. Don’t confuse symmetry for efficiency!

One of my constant bugbears about the Resolution Foundation is its complete fixation on static distributional analysis – that is, it will only ever look at the immediate and direct effects of some tax or policy change on various “winners and losers”, and virtually never considers the second-order effects on economic growth or other outcomes that we care about. This is like objecting to an increase in nurses’ salaries on the basis that patients, not nurses, are the ones in need, ignoring that higher salaries for nurses might improve care for people who use the NHS. It’s dumb when right-wingers do it, and it’s dumb when left-wingers do it.

When you buy stocks and shares, you are buying a portion of a publicly traded company that has received money for those shares, and may sell more later for more funds. A higher savings rate in the UK means a higher rate of investment, especially since UK savers tend to be biased towards investing in British companies (“home bias”).

Investing your money in productive and innovative businesses, rather than consuming it (by, eg, spending it on a nice boat or fancy holidays), isn’t just good for you – it’s good for the people who work for those companies and who buy their products.

And unfortunately the UK has a very low investment rate. It’s one of the main reasons we’re so poor: more investment means better equipment, training and machinery for workers, which means they produce more and can demand higher wages. We sometimes flatter ourselves that we’re a research-driven economy, but we spend less of our GDP on R&D than the OECD average and much less than places America or Germany – 2.4% compared to over 3% by them. South Korea spends nearly 5% of its GDP on R&D! (NB, this chart has an out-of-date figure for the UK – we’re at about 2.4% now.)

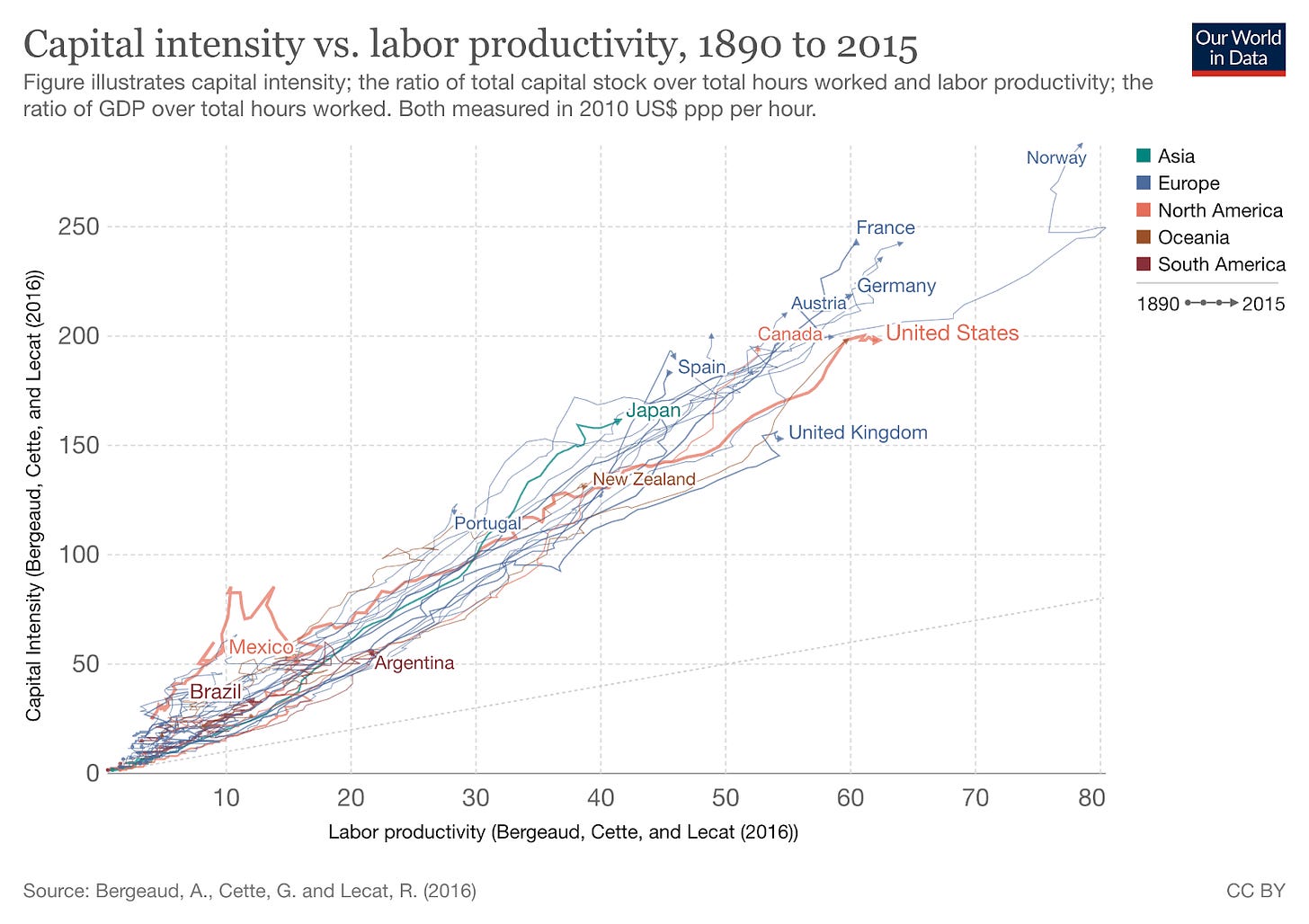

Here’s capital intensity tracked against labour productivity over the 20th Century. Note the UK’s position.

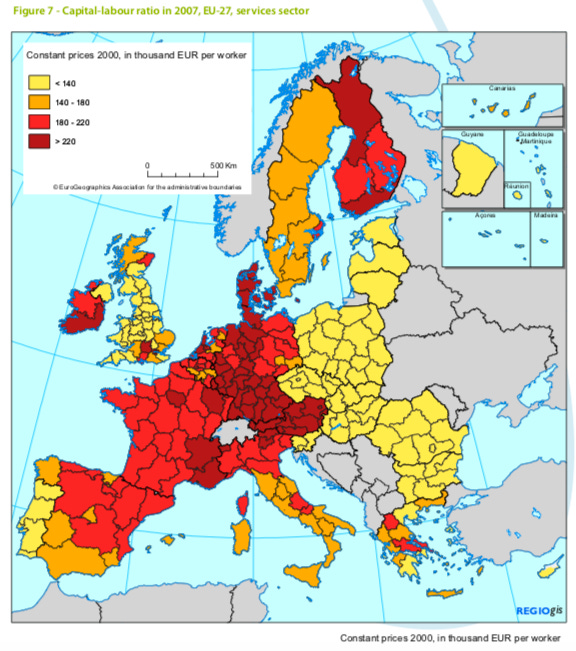

And check out this map of capital-to-labour ratios across Europe for the services sector, our most important sector.

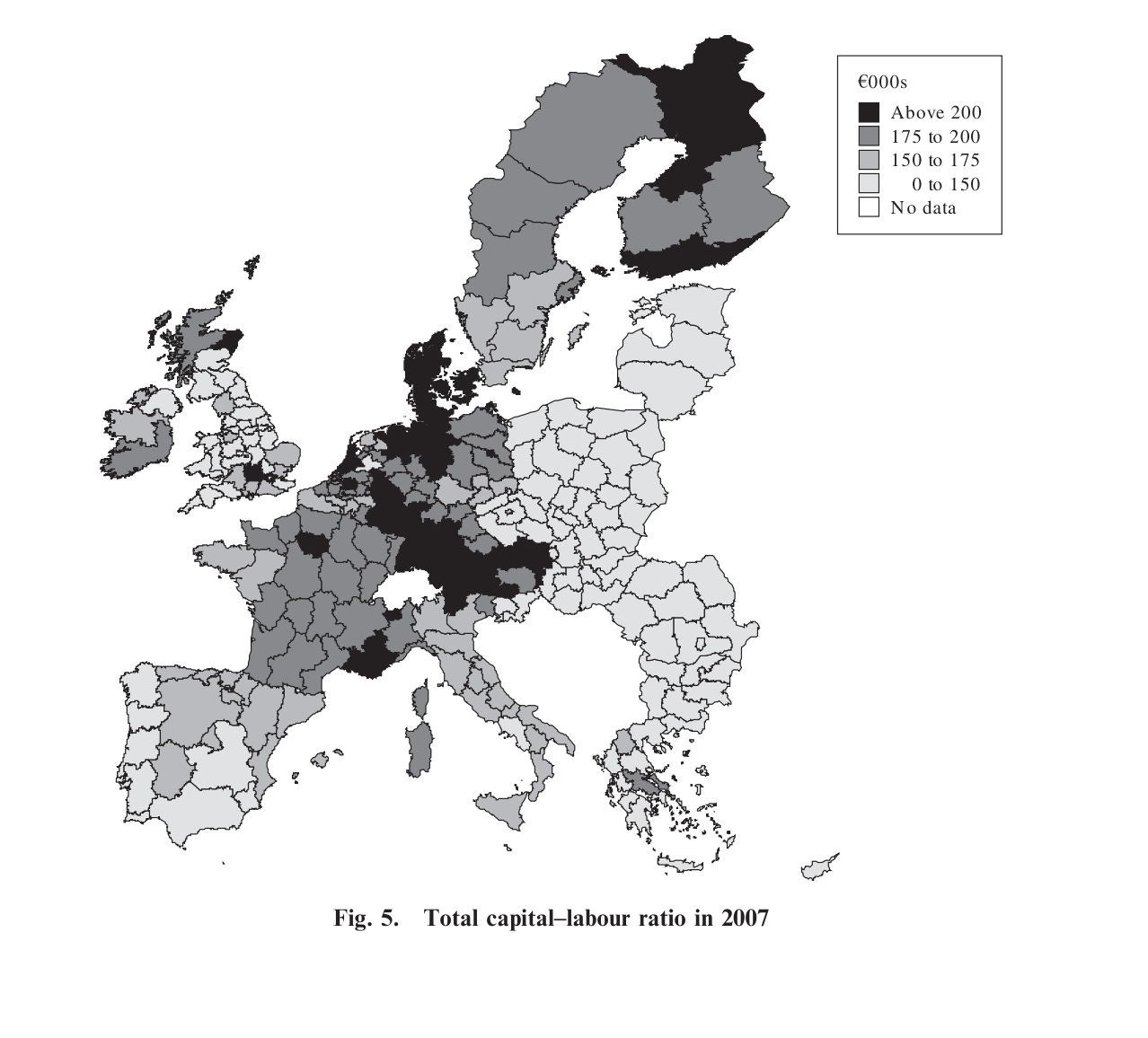

And here’s the overall capital-to-labour ratio across the whole economy:

Here Britain looks less like France, Germany or the rest of Northern Europe than it does like Greece or Italy – and those have been our economic peers for a while now. Does this look like a country that should be taxing investment more?

Resolution acknowledges that low savings rates might be a cause of low investment and productivity in the UK, but ignores altogether the fact that people may well invest less if you taxed them at 33–39% more on their returns as they propose. But if they did, and responded to these taxes by moving some of their ISA savings away from equity investments and into housing, consumption, or left the country altogether to avoid these new taxes, investment and productivity in the UK would suffer. It is really weird to write a report in a country in the midst of a 15-year productivity crisis without considering this.

The Resolution Foundation wants higher taxes on ISAs in order to use the money to subsidise poorer people’s savings. It is awful, and a huge policy failing, that so many people on low incomes live from hand to mouth and have to go into debt to deal with unexpected expenses. But the lack of savings is a symptom of their much bigger problem – that they are on such low incomes. The fact that they are not putting their scarce incomes into savings reflects that they have higher priorities, like keeping their families warm and their children fed and clothes. (Remember that this is at least partially driven by the UK’s chronically low levels of investment, so if the Resolution Foundation’s proposals reduce aggregate savings and investment in the UK, they will make this situation worse for them.)

Giving poorer people money is a very good way of addressing this, and we should do it more. Giving poorer people money but only on condition that they save their other cash is a terrible way of helping them. They have bigger problems than a lack of savings, and we should let them allocate whatever extra money we can give them however they think will help them best.

Ben Gardiner pointed out on Twitter that RF has slightly undermined its own numbers by citing the pensions Lifetime Allowance as a precedent. In that case, an extra tax was imposed on pension pot savings above, at the time, £1.5 million. Resolution just wants to do the same for ISAs, and the revenues it says it would raise – £1 billion – are derived from assuming normal taxation of anything above that.

However, as Ben points out, the Lifetime Allowance actually involves the precedent that existing pots would be partially protected from this kind of taxation. People with pots that were already above the threshold were eligible for a higher individual rate that protected their existing pension pots from the new allowance – so it only affected pots that hadn’t yet reached that point. So if that precedent is anything to go by, the Resolution Foundation’s numbers could be way off, and its proposals would actually raise virtually nothing in the short run, and would depend on people continuing to save in taxable ways, rather than putting it into untaxed housing wealth, or consuming it, etc.

So there’s not very much upside in this proposal for anyone. Let’s hope this is the end of it.

This article is republished from Consumer Surplus. Read the original here.