In Japan, around 25 per cent of people are over the age of 65. That is set to rise to 40 per cent by 2060. Meanwhile, the number of babies born there is at its lowest since records began.

This isn’t just a problem for Japan. All around the developed world a so-called “demographic time bomb” is threatening future prosperity and advanced economies face some tough choices.

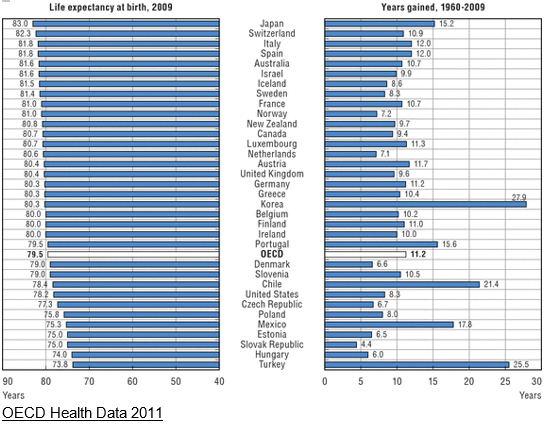

Reports from the Department for Work and Pensions released last week suggest that the retirement age will have to be raised, with those under the age of 45 having to work a year longer. Inevitably, as life expectancy continues to rise (something which should, of course, be celebrated) and birth rates drop, this will barely scratch the surface. Bolder action is needed.

As older people heap pressure on social security, and a lower birth rate means there are fewer people of working-age in the economy, those in the middle are feeling increasingly squeezed and reluctant to have more kids – and the vicious circle keeps tightening.

The emerging demographic imbalance is fiscally unsustainable for modern welfare states. From 2010 to 2016 total pensions spending increased by 25 per cent in the UK. More generally the imbalance is already hurting economic growth.

The “baby boomers” have had it good, and millennials will not be able to enjoy the same security. Pressure won’t just pile on the Government’s finances, but will pose a problem for businesses reluctant to shoulder the costs of more and more pension contributions, as the CIPD reported last year.

Meanwhile, the imbalance is so severe in Japan that some estimates suggest that its population could eventually shrink by between a third and a half. In Europe, the biggest imbalances are in Germany and Italy. The latter has the highest old-age-dependency ratio in Europe, with 34.3 persons aged 65 and over per 100 persons of working age (15-64).

Very broadly, there are two ways to slow, and one way to possibly even avert, the crisis: with a larger working-age population, and with politically and economically viable ways of looking after the elderly.

The key objective is to stem the decline in birth rates. China chose to phase out its one-child policy in response to concerns about its ageing population, but that is not a move available to other countries. Perhaps the most famous pro-natalist policy was the “Code de la famille” introduced by the French government in 1939, originally justified on national security grounds. Fortunately, the developed world today needs more children to become workers, not soldiers.

Governments are, of course, limited in what they can do. Many people would argue that the state does quite enough already, without intervening in the bedroom – although Spain had a good go, when it introduced a Sex Tsar to encourage babymaking. That said, common-sense reforms would include offering to ease the burden of childcare for young families by subsidising day care and the clever use of tax breaks.

Then governments should consider how to reach the untapped potential within working-age populations – largely due to inadequate female workforce participation, the skills gap and ageism.

Especially in countries such as Japan, and to a lesser but still significant extent Germany, the male-breadwinner model remains the default setting. This needs to shift so that women can be fully utilised in the economy. Policies such as equal pay and generous shared parental leave are not just the right thing to do, but will help defuse the demographic time bomb.

Meanwhile, too many young people in Europe languish in unemployment while vacancies go unfulfilled. There is no easy fix, but surely this problem can be minimised with greater coordination, including through demand-led apprenticeship funding and training schemes for young people.

Ageism in the workplace is another barrier to progress: increased participation at older ages both raises the tax base and reduces the spending burden.

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, immigration can present an effective solution to bolstering the working-age population. Given that the issue has become politically toxic in so many countries, there has never been a more important time to extol the virtues of immigration, which brings young, hard-working people to the places where they are needed.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel has flown the flag for migration in response to her country’s demographic challenges, and Germany will benefit hugely from it.

Everyone wants to make sure that those who can no longer earn money are properly looked after, and it is of paramount importance that the support is not compromised. However, innovative thinking is needed to work out how developed societies can continue to provide the care that’s needed. If the population forecasts are to be believed, then health services and government pension schemes will struggle to take the strain.

Japan is currently leading the way in fresh thinking on this subject. In healthcare, they have placed new emphasis on medical technologies, such as regenerative medicine, which will save money in the long term. The internet is being used more effectively as medical information is available online, encouraging self-diagnosis which can ease the pressure on services.

The most innovative solution so far, though, is Japan’s Long Term Care Insurance System (LTCI). Part insurance-based and part taxpayer-funded, when people turn 40 they are required to start contributing an affordable sum to LTCI each month, and they can begin claiming care at 65 or sometimes earlier. Implemented in 2000, not only is the scheme giving comprehensive, tailored help to the elderly, but it frees younger women – whose traditional role it was to look after their parents – to enter the labour market.

The demographic crisis facing advanced economies must not be faced, not ignored. Cross-party recognition of the problem and long-term vision are required for the necessary bold changes to be enacted. Societies also need the voices of millennials to be heard in politics: policies are too often geared to the views of their parents and grandparents.

For true change, a new social contract must be forged between the generations. Only then can the time bomb be defused.