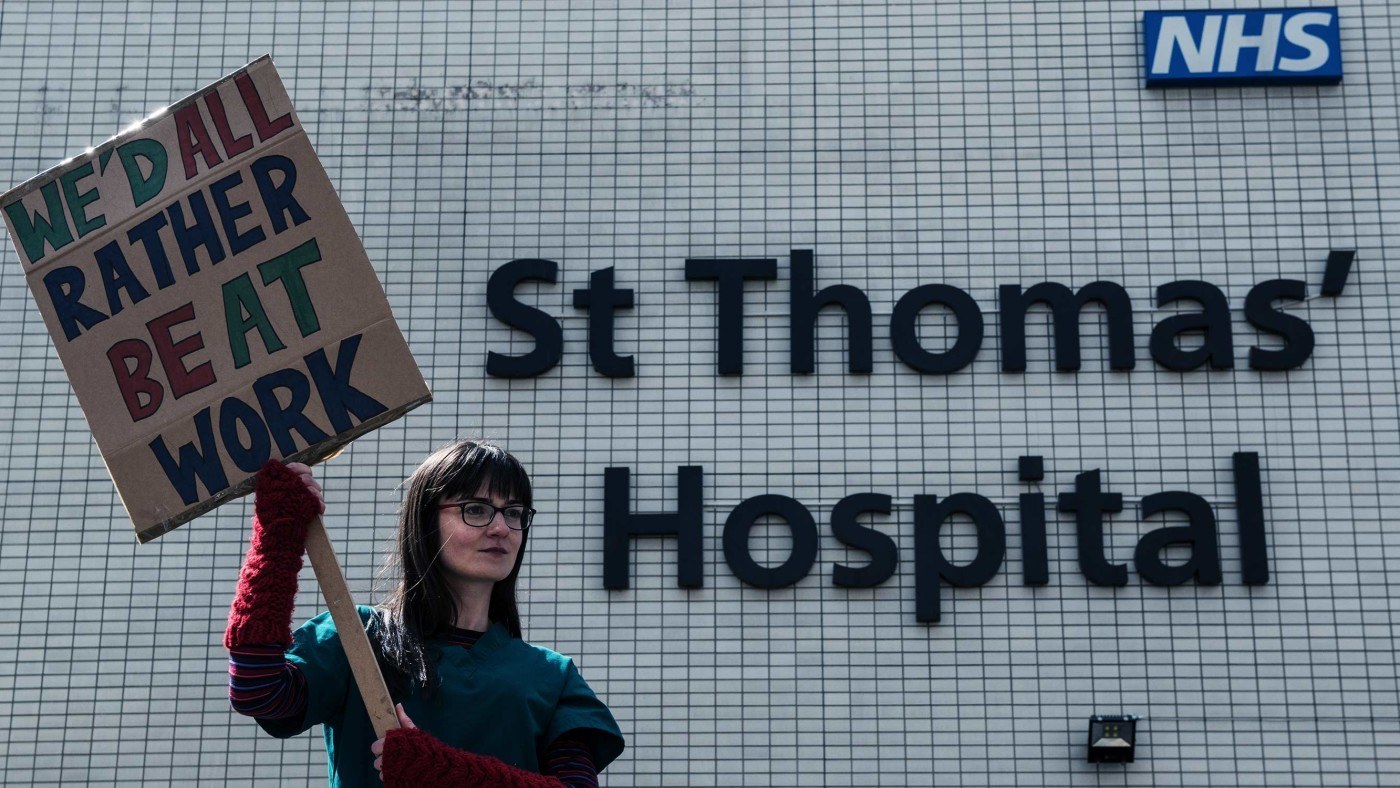

In a fight between junior doctors and a government minister there is only going to be one winner in the court of public opinion. Doctors train for years and are, we hope, there to help us when we fall ill. Government ministers, on the other hand, are almost as unpopular as journalists and estate agents. That is why, with the UK’s junior doctors on strike over a new contract which the government is seeking to impose, the health secretary Jeremy Hunt is under intense pressure and the striking doctors are generally portrayed as saints.

It may be that it was unwise of Hunt seek to impose the contract, although that action was only taken after years of meetings and attempts to get a deal. The doctors say their opposition lies in concerns about patient safety. The government says in response that the strikers have struck over their demand for more “premium pay” at weekends.

For me, it was that little phrase “premium pay” for weekend working that really stood out when I heard it this morning on Radio 4. How many other professions or trades offer “premium pay” for weekend working or working late? Not many.

If you are supporter of the junior doctors, and at this point you want to tell me you hope that I fall down the stairs today and then need the help of an absent doctor who is on strike, or declare that they save lives and ask what have I or any other non-doctors ever done for anyone, then please send CapX an angry letter or shout at me on Twitter. Abuse has certainly flowed towards journalists such as James Kirkup of the Telegraph. He in particular has written forensic analysis of the dispute and his latest epistle this week was an absolute belter of a piece that seems to have garnered him more abuse.

Of course doctors work hard and what they do is vital. They should be well-paid, and by most people’s standards they are well-paid. But they should not be immune from scrutiny on pay and conditions, or given a license to shout down the views of their fellow taxpayers who work just as hard and often for less reward in other parts of the economy. And there I wonder if the striking junior doctors have missed what has happened to other professions and trades, and whether some of them might be living in a medical vacuum after years of training with each other and other doctors.

Work has been transformed for most people in the last thirty years, in a tumult of social and technological upheaval. Some of it has been positive. It is easier for companies to hire (the flipside of it being easier to fire people); technology has in many industries reduced drudgery; the workplace is generally safer and cleaner; there is more flexibility; and most importantly of all, whole swathes of the economy that were male-only or male-dominated are now open to women. That’s the upside.

But for many people – those who are not necessarily thrusters and just want a decent life for their families – the dislocation and sheer pace of change has been profoundly unsettling. While there is a dispute among statisticians (particularly in the US) about precisely how many jobs a worker will have in a lifetime, and it is hard to measure with precision, there is no doubt that job insecurity in the private sector is much greater than it was in the 1960s. And at the bottom of the pay scale life is especially tough.

In better paid parts of the economy, think of your friends and ask how many employers they have worked for in the last twenty years. Not many will be able to say, like a doctor in the NHS, “one.” This personal turnover is broadly accepted by many people in my experience, because they are realists and instability is balanced by those positives I mentioned earlier. But then I’m a hack in the media – a trade not a profession – and many of us are used to the Grub Street tradition and never had any illusions about it. Many other people have had to get used to vast amount of change in law, retail, energy, construction and so on, where contract working and lack of tenure has become more common. It means moving around, looking for opportunity, and retraining, which is all fine, up to a point, as long as well-paid people with security and healthy pensions don’t complain that they are being particularly ill-treated.

Many non-NHS workers have also had to get used to the reality that their pensions – if they have one – won’t amount to much and that retirement is a fantasy. It is, then, with a certain amusement that those without large pension pots hear junior doctors say – on Twitter when they are defending the strike – that they’ll retire with a modest pension pot of £1m (and that is an underestimate if they do especially well).

And what of the hours? Of course junior doctors work anti-social hours, but they are hardly alone in doing so. Members of the armed forces; social workers who go the extra mile out of hours; the people who keep the food and logistics network running (no-one ever writes about them); the people keeping the lights on; small business owners; and the people working at the weekend at home to prepare for the next week at work, all of them go above and beyond. Of course most of those people will back the doctors in this strike, recognising that what they do is not easy. But I don’t think that doctors should assume voter patience is infinite.