There’s plenty in the Government’s inbox, but here’s yet another problem that ministers are going to have to urgently wrestle with – housing.

Over the past year, the stock market has been dropping. Since January, the FTSE 100 is down 7%. Even more worryingly, the FTSE 250 – which may be a better metric of the UK economy as it has fewer global firms – is down 27%.

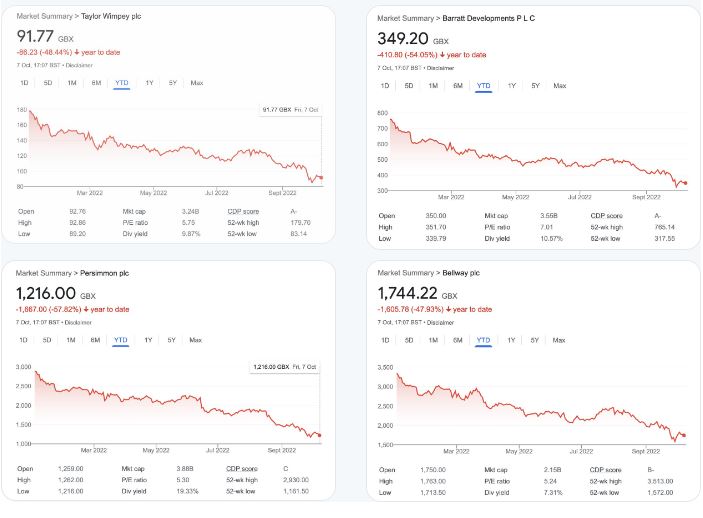

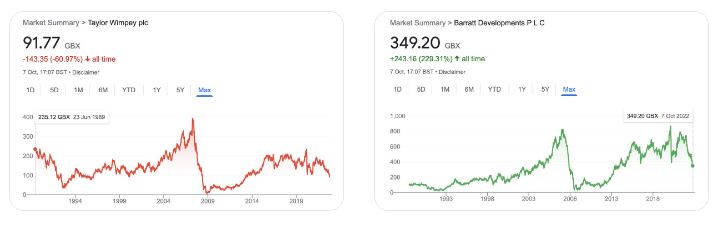

The housebuilding sector in particular has taken an absolute battering. The share prices of the four biggest volume housebuilders in the country have all cratered. Berkeley, the fifth largest firm, has done a bit better because it has a different model, focusing on high quality homes in London. But collectively these five firms have seen their market capitalisation go from £32.7bn to £16.4bn – in other words, almost exactly halving.

.

Why has this happened?

There are lots of little explanations (cladding, potential falls in house prices, and so on), but the big one is that the market is expecting these firms to build fewer houses in the coming years, and hence make a lot less money.

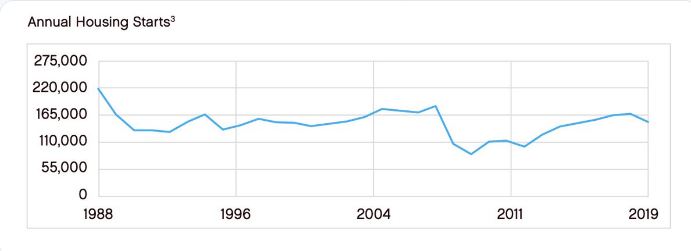

This is a completely rational expectation. Whenever the economy goes into recession, or interest rates spike, housebuilding tends to fall. It happened in 1987 and 2008 – and as work from the Centre for Policy Studies has shown, the sector generally takes much longer to recover than the economy as a whole (see below).

.

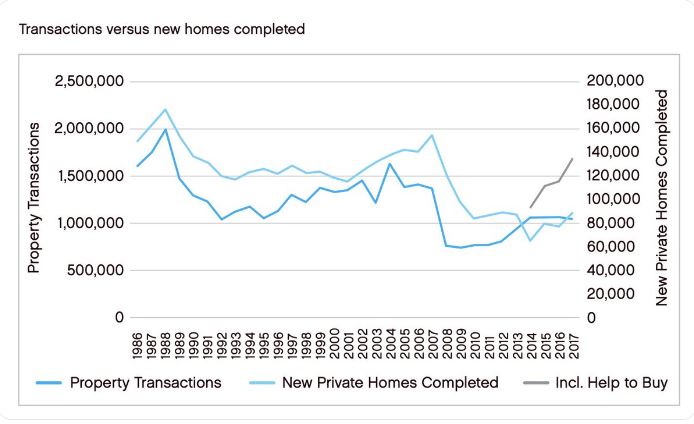

Higher interest rates mean people find it harder to get mortgages on houses. They also mean fewer transactions, which is almost perfectly correlated with housebuilding. After all, if people are buying lots of houses, builders tend to build more of them, as they can be certain of a sale.

.

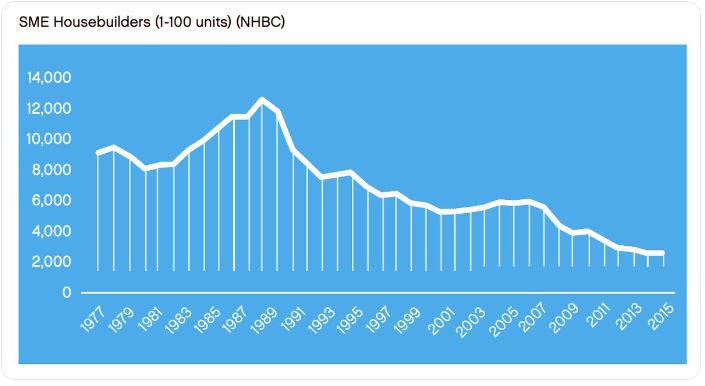

In short, even with the help of the Stamp Duty cuts in the mini-Budget, we are probably heading for a slowdown in housebuilding. This will be particularly bad for SME builders, who tend not to have the cash to weather downturns, as this chart shows.

.

As several people have pointed out, this will also hit affordable and social housing, since much of it is funded by levies on development, or forcing developers to build a chunk of affordable housing as part of the project.

I should stress that – on the share price metric – we are nowhere near where we were in 2008 (see below). Nevertheless, the markets are very clearly expecting fewer homes to be built.

.

This is where the Government comes in. They have said they want to build more homes, but also that they want to replace ‘top-down Stalinist housing targets’ with better incentives for councils and communities.

Better incentives are always good, but the thing is that the current system is built on those ‘top-down targets’. There is a wide range of possible reforms available, such as abolishing local plans and the requirement for councils to identify a five-year land supply; making them voluntary not compulsory; weakening the planning inspectorate; altering the presumption in favour of sustainable development; rework the calculations on housing need, or trying to push all new housing to brownfield and Investment Zones.

Many of these options would qualify as ‘abolishing top-down targets’. But many of them would also cause housebuilding to fall off a cliff. Already councils have been pausing local plans while they wait to see how much easier they will have it.

And even if you argue that the new Investment Zones will take the new homes, there’s a risk of dismantling the existing housing system before those zones are in place.

All this would not only make the housing crisis worse and entrench the power of the big housebuilders, but hit the economy very hard indeed. Back in 2010, a paper from estate agent Savills and Oxford Economics calculated that building an extra 100,000 homes a year could raise GDP by 1%. I haven’t run the numbers, but it’s pretty obvious that if you end up building, say, 50,000 homes a year fewer, there will be a proportionate hit to the economy – enough to outweigh the impact of much of the supply-side reform in the Growth Plan, and maybe even most of it.

Just as importantly, it also means that we will be building fewer homes at the time when we need to be building far more, because the housing crisis is blighting the lives of millions of people. There is widespread agreement that the housing system needs a greater focus on community consent, and greater local control over what is built. But we need to ensure that whatever new measures are introduced do not give Nimby voices an even stronger veto.

Ultimately, if the Government makes it even harder to build, at a time when rising interest rates are already chilling the sector, it will hit growth, reduce opportunity and damage people’s lives.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.