On Monday, the Brexit negotiations begin. It is hard to imagine – without the assistance of a committee of Hollywood scriptwriters or mind-expanding hallucinogens – how the circumstances could be worse.

Theresa May has power, but not authority. Her own Chancellor is campaigning for a jobs-first Brexit – code, many suspect, for no Brexit at all. Other ministers are reportedly allying with their Opposition counterparts to undermine her strategy. Her Brexit department has had half its ministers replaced, and she has lost her own top aides. Labour have a manifesto that commits them to hard Brexit, but a parliamentary party and electoral base that do not seem to have read it. Mrs May’s new partners, the DUP, have their own ideas – as do her European counterparts. The position is so muddled that we couldn’t even send over the paperwork outlining what we wanted to talk about.

Beyond all the technicalities – which are both vitally important and ferociously complicated – there are two competing visions.

One is, effectively, no Brexit: or rather, something that calls itself Brexit but is as close as humanly possible to the existing arrangements. Above all, it means continued access to European markets on current terms, even if that involves accepting free movement (with cosmetic restrictions) and continued payments to the European budget.

The other, normally called hard Brexit, is actually just Brexit. Britain would gain control of its borders and laws, and be able to strike trade deals with other countries, even if it would retain the closest possible ties to Europe – and might accept some (or much) EU regulation, or continue to pay for some of its projects.

Rhetorically, both of these end up in much the same place. But their essentials are very different. One starts with In, and moves Out. The other starts with Out, and moves In. That is why their “fail states” are very different too. The first is the status quo, but worse. The second is crashing out into a brave and uncertain new world.

The voices calling for “In then Out” are not just sore-loser Remainers. Earlier this week, the Strand Group at King’s College London hosted the launch of a new report co-authored by Ed Balls on what medium-sized businesses want from Brexit. The answer is simple: the status quo, or at least plenty of time to adjust. A predictable finding, yes. But Balls hasn’t simply invented the business leaders he quotes. Hammond, too, speaks with their voice.

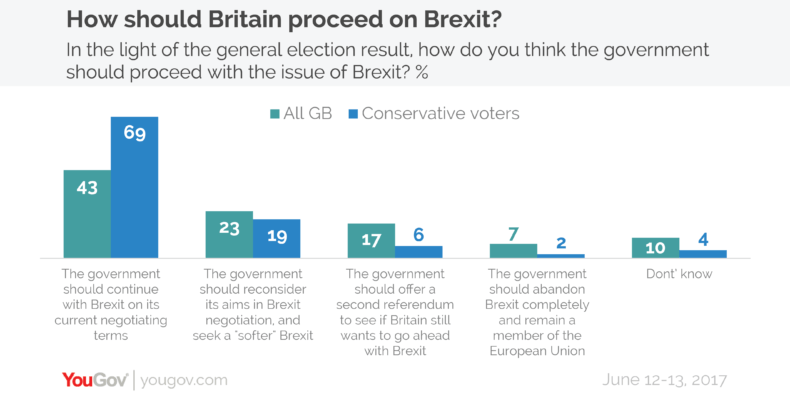

Yet despite this, the public still seem keener on “Out then In”. A YouGov poll on Thursday found that 43 per cent of voters still back May’s approach – not a majority, but considerably more than the 23 per cent who want “soft Brexit”, the 17 per cent who want another referendum, or the paltry 7 per cent who want to call the whole thing off.

There are, therefore, two key questions. Is there a workable majority for this kind of Brexit – or any kind? And at what point does strategy become subordinate to timing?

In terms of getting us closest to what most Britons seem to want, the May approach still wins. We thrash out the closest possible trade deal (not least by using future contributions to the EU budget as leverage) but retain our freedom in other respects. Ideally, we also cushion the transition with some kind of interim deal.

The problem is that all this will be fiendishly hard to negotiate – and the clock is ticking. With every day Britain spends mulling over the kind of deal it wants to see, it becomes less likely that it can get any deal at all.

That tilts the calculation back towards a safety-first Brexit. But that, in turn, betrays not only the millions of Leave voters who wanted actual change, but the future opportunities that Brexit was meant to deliver.

All this leaves Mrs May, and the country, in a desperate fix. Unless she can somehow hammer out a consensus first within her party, and then within Parliament, our position will remain a muddle. And the only ones taking back control will be Michel Barnier and his team – both of the negotiating agenda, and of Britain’s future.

This article is taken from CapX’s Weekly Briefing email. Subscribe here.