The Joseph Rowntree Foundation has demonstrated, once again, that we British are very nice people. This isn’t quite what they think they’ve proven with their analysis of the minimum income standard but it is so – as it is so that we’re all very nice people.

The JRF’s claim is that, after after asking people what they think you need to get by, a single parent needs £29,000 a year to have that minimum standard, the nuclear family some £40,000 and so on. Given that these are the amounts people need, and that not everyone has what they need, Something Must Be Done. This time, that something is a higher living wage and perhaps an increase in welfare spending.

There’s nothing wrong with the calculations that get people to £29,000 and £40,000. It’s akin to Adam Smith’s linen shirt. Not having one doesn’t make you poor, unless you’re in a society where not being able to afford one means you’re regarded as poor. The question, then, is what do we think the expenses are that constitute that minimum standard? Tot that up and we get to the above figures. Except there are two further problems here.

The first is that the country just isn’t that rich. That £40,800 for the two parent, two kid family is right on the verge both of the higher tax bracket (so we might regard them as being “rich”) for a single earner, and also right on the edge of being in the top 40 per cent of all households by income. We cannot all be above average.

The second is that while we might say we’d like everyone to be earning a certain amount, very few act as if we mean it. This is the economists’ insistence upon revealed preferences, not expressed. We might well say, in a focus group, that every kid should have swimming lessons. We’re really very much more reluctant to dig into our pockets to make it happen. That even Theresa May got 42 per cent of the vote demonstrates that nicely. Equally, the general popularity of the benefits cap shows that we’re not quite as generous when it comes to paying.

In other words, we’re just being too nice in the JRF’s focus groups.

Whether or not people actually want to guarantee what they describe as the minimum standard of living, trying to bring it about would play merry terror with the economy. Yes, I know, too many say that a higher minimum wage doesn’t cost jobs and so on but there’s no economist who would defend that position. Modest minimum wages, modest changes in them, might not cause much damage, might even, in the calculations of some, be worth it. But the important word there is modest – immodest levels are agreed to have large and detrimental effects. Vast swathes of the people would simply not being able to get proper jobs, as is true in India or South Africa, most therefore working in the “informal” economy.

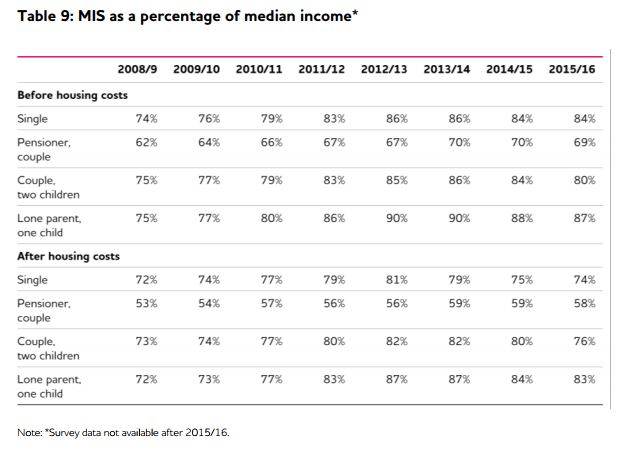

That brings the argument to the difference between modest and immodest changes in the minimum wage. There is no rule here, or only one of thumb: about 50 per cent of median wages, below that and there aren’t that many effects, above it all starts to bite. Which brings us to a slightly alarming part of their report:

We cannot, not without killing swathes of legal jobs, raise the minimum wage up to 84 per cent of the median. It’s also takes equality rather too far to insist that others must be taxed so as to near equalise incomes in this manner. Why would anyone strive mightily if the outcome is always going to be around median? Note that if everyone below median is to be brought up near to it then by definition everyone above must be brought down to near it. That’s how medians work.

The JRF has, once again, showed that we’re all very nice. We desire that everyone have what we consider to be a reasonable standard of living and there’s nowt wrong with that. As a guide to actual policy it’s not that useful, because what we then go and do about it, our revealed preferences, tells us that we are just being nice to the men with the clipboards. The country isn’t rich enough for everyone to have that desired lifestyle and more than that, we’re not prepared to pay for them to do so either.