Nobel laureate Robert Shiller has written about the need for economists to take greater account of narrative in their analyses. The stories that people tell themselves and each other, whether or not in fact true, not only shape the understanding by future generations of economic events – consider the Great Depression, or 1970s stagflation – but they also have important consequences for contemporary economic developments.

Investors’ periodic swings from gloom to optimism to euphoria and back into despondency – Keynes’s “animal spirits” – move markets and decide the future of firms and even entire countries. Prevailing narratives can become self-fulfilling prophecies. The Brexiteers realise this: barely a day goes by without pessimistic comments by officials about the economy’s prospects being followed by accusations of “talking down the economy”.

Narratives can also have highly consequential policy implications. Consider Donald Trump’s insistence, which many Americans have taken to heart, that the United States is being “killed” in its international trade with China and Mexico. What was a cranky tweet a few years ago is now the official view of the US government. It could result in the abolition of Nafta – and a major blow to globalisation.

In Europe, the persistent narrative that the euro cannot work did much to undermine macroeconomic stability in 2011 and 2012, as yields on peripheral-country bonds skyrocketed. Meanwhile, the conventional account that immigration is harmful to public services and social cohesion, despite the lack of evidence, continues to shape government policy towards foreign workers all around the rich world.

Few sectors have been exposed to the consequences of public narratives in recent years more than finance. An example is the fear that Brexit might lead to a “bonfire of regulations” which will lead the UK back into a supposedly “Wild West” of speculative activity in the pre-crisis years.

It’s a compelling story. The only problem with it is that it’s totally fanciful. There won’t be a bonfire of regulations because the Government has made it clear that it prioritises regulatory equivalence with the EU over any legislative changes which, however desirable they might be for Britain’s financial sector, might compromise trade with European countries.

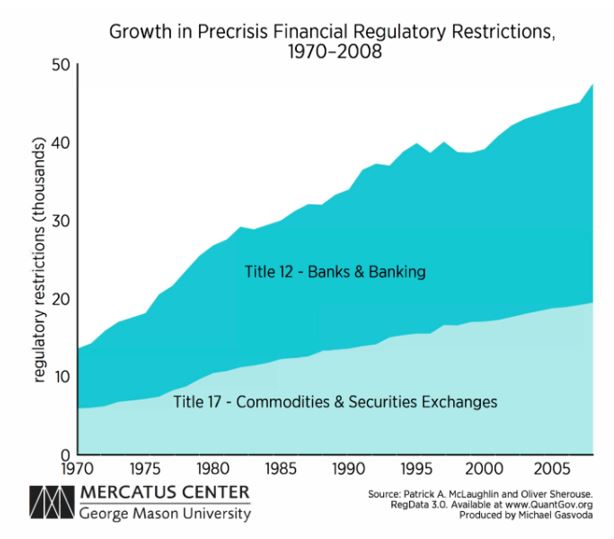

Similarly, finance was anything but a free-for-all in the run-up to the 2008 crash. This is true for both the US and the UK. Regulatory restrictions on the financial sector followed a steady upwards trajectory in the 38 years to 2008 (Fig.1). Of course, in the aftermath of the crash the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act – which all in all comes to 30,000 pages of legislation – has turned up the pace of intervention.

Fig. 1. Pre-crisis regulation in the United States, 1970-2008

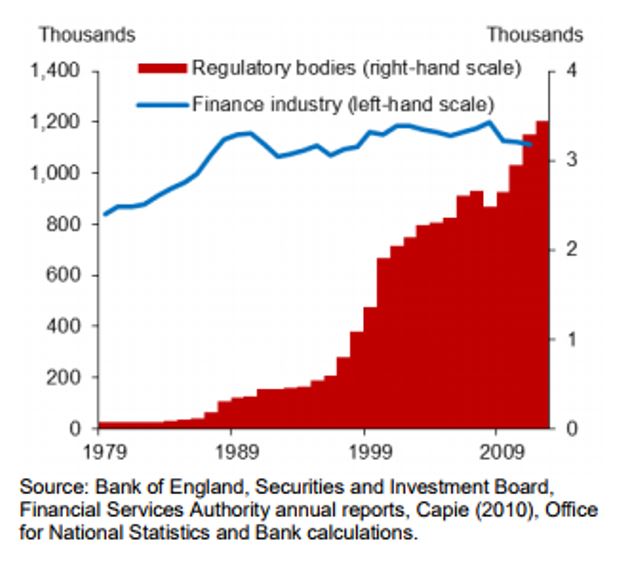

Similarly, in the UK regulatory growth has been relentless since 1979 (Fig.2). In 1980, there was one regulatory official for every 11,000 financial services employees; as of 2011, there was one for every 300.

Fig. 2. Number of UK financial services employees (LHS) and of financial regulators (RHS)

Part of the increase was surely due to the need for greater supervision following Big Bang and the internationalisation and diversification of British finance. But that doesn’t take away from the point that regulatory pressure was anything but light-touch during the period. It is also likely that growing regulatory obligations may have played a role in keeping the costs of financial intermediation from falling, a development which some suggest lies behind Britain’s tepid investment and productivity performance.

That false narratives such as that of a Wild West financial sector and a forthcoming regulatory bonfire give an inaccurate picture of the past is obvious. The bigger problem, however, is how they hinder our ability to adopt sensible policy reforms which would do much to improve Britain’s economic prospects.

I barely need to mention that EU legislation has often worked against the interests of British industry, even when adopted at the behest of British officials. The regulation of hedge funds and other alternative investment managers, bonus caps, and the crackdown on proprietary trading, were all wholly or partly designed at EU level. Yet, they are tangential to achieving systemic stability and well-functioning financial markets and should therefore be the subject of post-Brexit legislative scrutiny. But the narrative of a bonfire makes this improbable.

Likewise, Britain’s poor productivity record, which is responsible for sub-par wage growth, can scarcely be addressed whilst firms’ cost of capital remains so high. Regulation and compliance costs are a key determinant of the ease of funding, which means that without a willingness to revise existing burdens the problem will prove hard to tackle.

In the grip of the Great Depression, US President Franklin Roosevelt said that the only thing Americans should fear was “fear itself”. In post-Brexit Britain, one may fear many things, but one of them is surely the power of simplistic narratives to lead us down the path of stagnation and despondency.