This week CapX is republishing some of our favourite articles of the year. This piece first appeared on June 8.

Just a few years ago the smart thing to say about Pakistan was that the days of military coups were behind it.

“It can’t happen,” the then US ambassador to Islamabad told me in 2012. “For one thing, there are too many TV stations. Think of how many they would have to take off air!”

The ambassador had in mind the coup of 1999, the last time the army helped itself to power. In those analogue days it was a cinch. A few troops motored into Islamabad and scaled the front gate of state broadcaster PTV. The country’s only television station was under army control. Job done.

Today there are so many channels it is hard to come up with an authoritative number. They broadcast in different languages and from different locations across the vast country. Curiously, it was the coup-maker himself, army chief Pervez Musharraf, who permitted rambunctious news channels to grow like Topsy. The rise of cheap, internet connected devices has opened the floodgates of social media, further adding to the difficulties of ambitious generals.

And yet Pakistan is once again in the throes of its latest military takeover.

You can be forgiven for having missed it. The world’s attention has been glued to international crises elsewhere. And the takeover of 2018 is a “soft coup”. It is far slower and subtler affair than the old-school coups of 1958, 1977 and 1999.

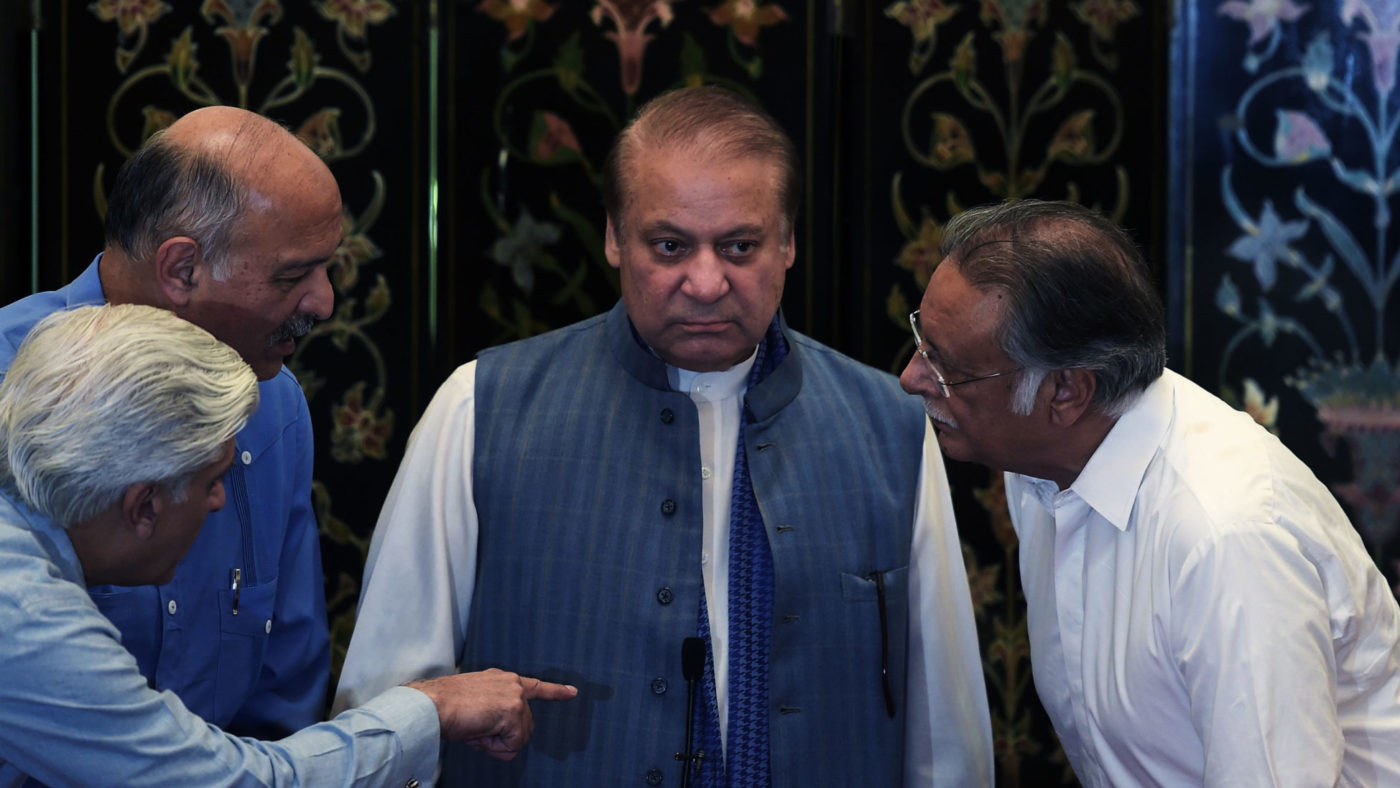

Ostensibly the democratic set-up remains intact, with the country gearing up for general elections to be held on July 25. But although the faction of the Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N) led by Nawaz Sharif has been in government since its landslide victory in 2013, it has not been in power for some time. It has been steadily hobbled by a military establishment that has waged guerrilla war against Sharif, preventing him from achieving his main priorities. That included an effort to put Musharraf on trial for high treason and making peace with India. Towards the end Sharif’s government was so enfeebled that the army’s spokesman was able to casually dismiss a prime ministerial directive with a Tweet.

Last July Sharif was removed from power by the Supreme Court for a minor misdemeanour: he had failed to declare a small income from one of his son’s companies which he was entitled to but did not collect. Pakistan’s activist judges are thought to have been handed that titbit by the country’s military intelligence agencies as part of a probe into the prime minister’s financial affairs.

Sharif is attempting to fight back with barnstorming rallies in his native Punjab, a key province. But he has received scant coverage from all those private television stations. Without seizing a single TV station the army has brought the entire media to heel.

Vast damage has been done to press freedom along the way. Off-message journalists have been threatened and abducted. In April the country’s biggest channel, Geo, which was deemed to be pro-Sharif, went off air in most of the country. Cable companies had been told to drop the channel. Newspapers owned by the media group also disappeared from newsstands. The stranglehold was withdrawn after it made peace with the army and recalibrated its coverage. Several of the media group’s best writers have been reduced to posting their columns on Twitter because their newspaper will no longer publish their thoughts.

Dawn, a highly respected liberal English-daily, has been under siege after it ran an interview in which Sharif implicitly criticised the military for holding up the trial of the army-linked militants accused of masterminding the 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai. The army responded by going after the messenger: news agents were told to drop Dawn and the paper has vanished from military-owned suburbs in major cities. Its broadcast arm, Dawn TV, has also been widely blocked. The army’s commercial empire has stopped buying advertising space from the media group.

Social media has not been spared either. Online activists who disagree with the army’s view of the world have been kidnapped, tortured and accused falsely of blasphemy. Websites have been blocked, including Safe Newsrooms, a project to publicise media repression that was only launched two months ago. Its founder, the outspoken journalist Taha Siddiqui, fled the country after a botched kidnap attempt by military intelligence agents.

Monday saw the most blatant menacing of social media yet. The army’s spokesman announced at a press conference that the military was monitoring social media for “anti-state, anti-Pakistan and anti-army” material. He displayed a diagram of Twitter accounts, which included prominent journalists, that were suspected of being manipulated by “enemy designs” (for which, read India). A few days later another journalist, the high-profile commentator Gul Bukhari, was picked up and briefly detained. Her abduction has been taken as a sign that no one is untouchable.

The army’s power grab is barefaced. But it is not a prelude to a formal coup. Most analysts think the plan is to deny the troublesome Sharif’s party another majority. PML-N candidates have been pressurised into defecting to the party of former cricketer Imran Khan. The army will likely be happy with an ineffectual coalition government led by Khan. That way the military can continue to pull all the strings that matter while avoiding the international opprobrium – and possible sanctions – of full-blown army rule.

The Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency, a think tank, has declared the pre-poll process “unfair”.

The army is playing with fire. Pakistani democracy may be messy, and often fails to deliver good government. But it does provide a peaceful channel for public anger in a country riven with ethnic fault lines and which is forever teetering on the brink.

Pakistan’s faltering economy is not providing the jobs and economic security demanded from a demographic “youth-bulge” of vast proportions. A nuclear armed state with 200m people may struggle to hold together if it is hit with a major, unexpected shock. A war, perhaps, with one of the three neighbours it has dreadful relations with. Or a natural calamity – a drought or earthquake. Or perhaps the sort of under-the-radar spike in global commodity prices that some believe triggered the Arab Spring.

The army does not believe in democracy as a safety valve. It prefers to keep a lid on things with force and repression. Its ongoing response to the recent mobilisation of Pashtuns, an ethnic minority, is a case in point. Their grievances include anger at the “disappearances” (illegal kidnappings) and “encounters” (extra-judicial killings) members of their community have suffered during the counter-insurgency campaign against militants along the north-west border with Afghanistan. The army has responded to their rallies and protests with harassment, accusations of Indian meddling and a media blackout. It is hard to imagine a better way to radicalise a movement of young men who feel they have nothing to lose.

Despite this orgy of “pre-poll rigging”, the PML-N remains the country’s most popular party and Sharif its most popular politician, particularly in the all-important province of Punjab, according to Gallup. Those heartland voters will be deeply alienated if the army’s efforts to shut out their preferred party succeeds. And a government seen as illegitimate, or as an army puppet, will struggle to respond to crises.

Whether they are hard or soft, coups in Pakistan always end badly.