International attention was completely, naturally, absorbed by the German election in its run up and aftermath. Yet the Austrian vote at the weekend, just as interesting in its own way, warranted only a passing glance. The results in Austria are particularly interesting because they highlight three wider trends in European politics at the moment. These are: a shift to the Right; greater political fragmentation with strengthened extremes, and a transformation of political parties into “movements”.

The ballot also raises important questions about how best to beat populism and what impact a coalition government involving the far right will have on the spread of populism throughout Europe. For there are, remember, elections in Italy, Hungary and Sweden coming up next year.

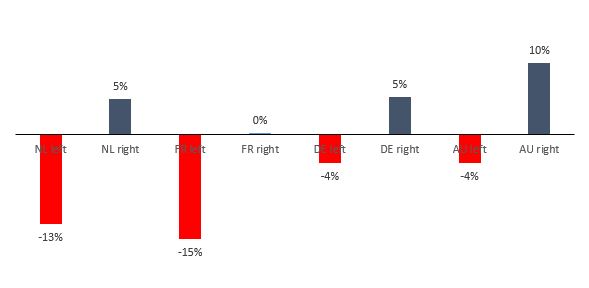

Figure 1: Fortunes of the Left and Right in the Netherlands, France, Germany and Austria in 2017 versus the most recent election in each country

The Left has been experiencing significant losses across Europe recently, while parties on the Right have made gains. This trend isn’t quite so obvious in France, because Macron’s La République En Marche! has been classified as centrist. But the increase in support for right-wing parties in Austria is stark: both the right-wing People’s Party (ÖVP) and the far right Freedom Party (FPÖ) made gains since the 2013 elections. It remains to be seen whether this trend will strengthen in those elections next year.

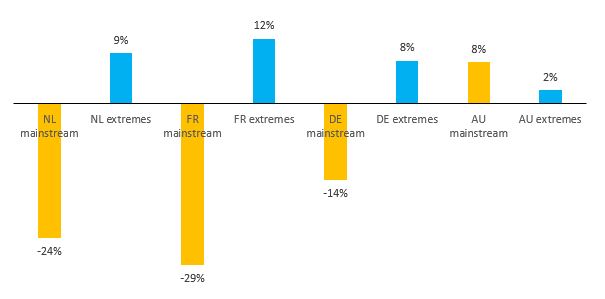

As for the second trend, political fragmentation and a move away from the mainstream parties, Austria gives the impression that it has side-stepped the fate of its neighbours. In the Netherlands, France and Germany, the combined vote share of the mainstream centre-left and centre-right parties dropped from 14-29 per cent between 2012/2013 and 2017. In Austria, on the other hand, it increased by eight per cent.

Figure 2: Fortunes of the mainstream (combined vote share of the main centre-left and centre-right party in each country) and the extreme parties on the Right and Left in the Netherlands, France, Germany and Austria in 2017 versus the most recent election in each country

However, this relates to the third trend: a transformation of political parties into ‘”movements”. While comparisons are drawn between the Austrian People’s Party leader, Sebastian Kurz, and the French President, Emmanuel Macron, the more accurate comparison would be with Justin Trudeau in Canada and Jeremy Corbyn in the UK. While Macron built a new movement from outside the party structure, Trudeau and Corbyn have transformed old, existing, establishment parties into anti-establishment, insurgent movements. They drew on the existing party funding and structure to achieve their goals.

Kurz did the same with Austria’s oldest conservative party – which in the past has been compared to the German Christian Democratic Union. He rebranded it the “Sebastian Kurz List” and changed the party colour scheme from a serious black to bright turquoise. And, like the Canadian Liberals and UK Labour party, his new People’s Party delivered a message of real change, modernised its use of online and social media outreach, and mobilised young voters.

During his speech on election night, Kurz told his supporters: “We have built a movement… this is our chance for real change in this country.” So even though the ÖVP is still be regarded by many as mainstream centre-right, Kurz’s leadership breathed new life into it – co-opting the language and substance of the populist Right – and made many voters view it as a new force for change.

Kurz did increase the ÖVP’s vote share from 24 per cent in 2013 to 31.5 per cent in 2017. But this now means there are effectively two populist parties instead of one. The stronger and legitimised far right – the FPÖ – also made gains. In fact, the biggest losers were the progressives. The Social Democrats (SPÖ), like Kurz’s conservatives, have also had to leave the door open to a coalition with the FPO.

This is an extraodinary result for FPO leader Heinz-Christian Strache, who has a well-documented, neo-Nazi past. Let’s not forget the previous EU sanctions against Austria for allowing a coalition with Jorg Haider’s FPÖ in the early 2000s, and the party’s Islamophobic and xenophobic positioning. But the fact that both the ÖVP and SPÖ were willing to partner with Strache in government has given the impression that the Freedom Party is a palatable option for government.

The SPÖ patently failed to learn the lessons of last year’s presidential ballot in Austria: that elections can be won with a bold notion of inclusive, pro-European national identity and a progressive platform. Barely a year ago, a Green candidate won over 50 per cent of the vote with such a strategy; progressives did not take note.

It will be interesting to watch, over the next few months, the impact that any Austrian coalition involving the FPÖ has on EU politics – and what happens to support for populist parties in those countries with elections yet to come.

As Heather Grabbe argues, it is unlikely, for pragmatic reasons, that Austria will go along with Strache’s desire to join the Visegrad group. But his expressed wish leaves little doubt as to the direction in which he wants to push Austria: closer to the increasingly illiberal Hungary and Poland. Macron’s ambitious plans for greater EU integration are also likely to receive a cold shoulder from Kurz.

Will Kurz’s success at the ballot box encourage other centre-right parties to adopt the populist tone and platform to win votes? And will centre-left parties figure out that the movement approach to politics, used also by Trudeau and Macron, works well to promote progressive, socially liberal, pro-EU causes too? All eyes are on Italy…