With the triggering of Article 50, Theresa May has set Britain on an irreversible course out of the EU. Many well-meaning Remainers on both sides of the Atlantic hoped that Wednesday would never come. They placed their hopes first in the British courts, then the House of Commons and, finally, in the House of Lords. One by one, the barriers to Brexit fell away.

“Do not underestimate the strength and maturity of British democracy,” I have cautioned my anti-Brexit friends. Well, March 29 has come and gone, and Britain, which joined the EU while at the nadir of her economic and political fortunes, is set to emerge from the EU full of confidence and vigor. Europe, by contrast, is facing an existential crisis.

Much to the dismay of my Conservative friends at St Andrews, I started my academic career as a believer in greater European integration. Central Europe, where I was born, was impoverished by communism, and membership of the EU seemed like a solution to many economic and political problems in former-communist countries. Over time, however, I started to see the costs as well as the benefits of the EU.

Why, I wondered in 2003, was it necessary for the EU to harmonise rules of production, environmental standards, and health and safety regulations? Productivity across the EU differs widely. In 2015, for example, GDP per capita in Luxembourg, the EU’s richest state, was 14.9 times higher than that in Bulgaria, the EU’s poorest state. In contrast, GDP per capita in North Dakota, which was America’s richest state in 2015, was only slightly more than twice as high as Mississippi, America’s poorest state.

By definition, regulations emanating from Brussels must be applied equally throughout the EU. Unavoidably, any that add to the cost of production have a more deleterious effect on less productive ex-communist countries than on more productive Western European nations.

Eastern countries, I felt, were right to complain about rules that were often made to enhance the already high standards in the West and which were, sometimes, meant to protect the interests of Western producers.

It was only later, though, that I embraced the Eurosceptic cause. While this was a gradual process, one event in particular helped to convince me that the EU has become pernicious and must be stopped. That event was the EU’s handling of the French and Dutch referendums on the EU Constitution in 2005.

After the people of France and Holland rejected the EU Constitution in their respective referendums, the EU establishment relabelled it as the Lisbon Treaty and adopted it nonetheless. As Jean-Claude Juncker, head of the European Commission, said of the 2005 French referendum on the Lisbon Treaty, “If it’s a Yes, we will say “On we go”, and if it’s a No, we will say, “We continue.’”

What made things worse was the way in which Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, who needed to weasel out of their “iron-clad” promise to hold a referendum on the Constitution, sold the Lisbon Treaty to the Eurosceptic Brits as a substantially new document. At that same time, the German leaders were reassuring their people that Lisbon was a carbon copy of the rejected EU Constitution.

Such acts of deceit and arrogance convinced me that the EU establishment held the people of Europe in utter contempt and that it would stop at nothing in pursuit of an “ever-closer union”. It showed me that the EU bureaucrats see themselves as a class of wise experts who assume they know how society ought to be organised. And that raises an interesting question: Does an “enlightened” class of well-meaning technocrats have a right to make people free or happy or, simply, better off?

Speaking of being better off, Remainers must acknowledge that Europe’s problems reach far beyond the EU’s democratic deficit. I am convinced that the process of European unification would have continued, had the EU lived up to its own rhetoric and delivered growth to the European continent. Regrettably, it has failed to do so.

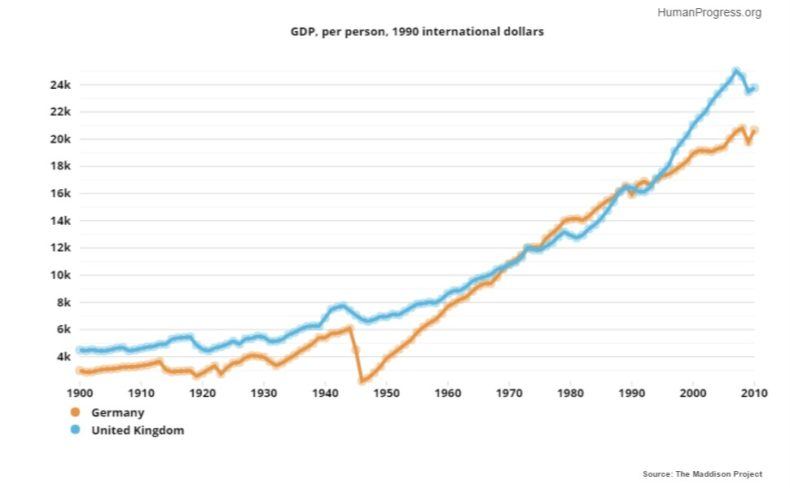

When the UK joined the EU, it was in the midst of a debilitating experiment with democratic socialism. A country that was on the winning side of two world wars was surpassed by West Germany in terms of GDP per capita. Mistakenly, Britain credited membership of the European Economic Community for the West German economic miracle. In fact, the West German miracle had little to do with the membership of the EEC. It was, by and large, a result of domestic economic reforms.

The West German post-war recovery started in 1948, when Ludwig Erhard, the German economics minister, reformed the currency and removed the Nazi price and wage controls, which had been kept in place by the victorious allies. The EEC came into effect in 1958 and intra-European tariffs on trade were not fully eliminated until 1968 – two decades after the beginning of the West German miracle. Logically, therefore, the EEC could not have been responsible for returning West Germany to growth or for its economic expansion during the 1950s.

Whatever the salutary effects of the EEC actually were, they did not last. By the mid-1970s, West German Wirtschaftswunder, French trente glorieuses, and Italy’s il miracolo economico came to an end as stagflation set in. Far for being credited with Europe’s post-war prosperity, the EEC was considered a disappointment. It did not, contrary to popular opinion, upend protectionist policies among European nations and bring about higher growth.

The Dooge Report of 1985 called for a fresh start. Under the Single European Act of 1986, which was signed by the otherwise Eurosceptic Margaret Thatcher, the national veto was replaced with qualified majority voting and European institutions were tasked with turning the common market into a truly free “single market”. The SEA turned out to be a double-edged sword.

On the one hand, the newly-empowered European institutions successfully broke down many internal barriers to trade. As a consequence, trade in goods is now largely free. When it comes to services, however, protectionism continues to reign. In the early 2000s, Frits Bolkestein, who was the EU Commissioner for the Internal Market, proposed the so-called Bolkestein directive, which would have greatly liberalised trade in services in the EU. His initiative failed. That’s particularly disappointing, considering that services account for a majority of economic output in all EU economies.

On the other hand, Brussels used its new power to overregulate economic activity. This process gathered speed after the signing of the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, which created the modern EU. Hundreds of thousands of directives and regulations – dealing with everything from the labour market to the electric power consumption of toasters – poured, and continue to pour, out of Brussels.

This regulatory overdrive may justify the well-paid jobs of EU bureaucrats, but it stifles competition within Europe and makes Europe less competitive globally. In 2004, for example, the 28 member states of the EU were responsible for 31.4 per cent of the global economic output. By 2014, that share fell to 23.8 per cent.

Over the last 60 years, the EU has grown from a free-trade area and a customs union among six Western European countries, into a supranational entity that governs many aspects of the daily lives of 508 million people spread across 28 European countries. It has its own flag, anthem, currency, president (five of them, to be precise), and a diplomatic service.

Europe’s elite has been so busy building and enlarging the European institutions that they have ignored their primary task: to make Europeans better off. The British people concluded that they are more likely to prosper outside of the EU. Others may yet follow their example.