Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 12 October 2015 – 24 January 2016

Sometimes it’s hard to grasp just how impressive the Ancient Egyptians really were. The sheer scale of their achievements is mind-boggling, from the architectural wonder of the pyramids, to the intricacy of the afterlife customs which terrifies and entrances in equal measures. Even the length of their dominance is often severely underestimated. The starting point for Egyptian civilisation is usually pinned at around 3150 BC, with Egypt’s golden age of technology and art occurring between 2686-2181 BC. That means the Cleopatra, who died in 30 BC, lived closer in time to us today than to the building of the great pyramids.

It is with this in mind that I headed to Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom at Metropolitan Museum of Art. This exhibition focusses on a metamorphic period of Egypt’s history (2030-1650 BC), narrating Egypt’s development through 230 objects, from statues to jewellery to wall paintings. Adela Oppenheim, one of the Curators, explains that:

“The Middle Kingdom was an era during which the ideas and concepts that formed the basis of ancient Egyptian civilization were dramatically transformed, sparking the creation of amazing works of art that remain compelling, immediate, and often poignant, thousands of years after their creation.”

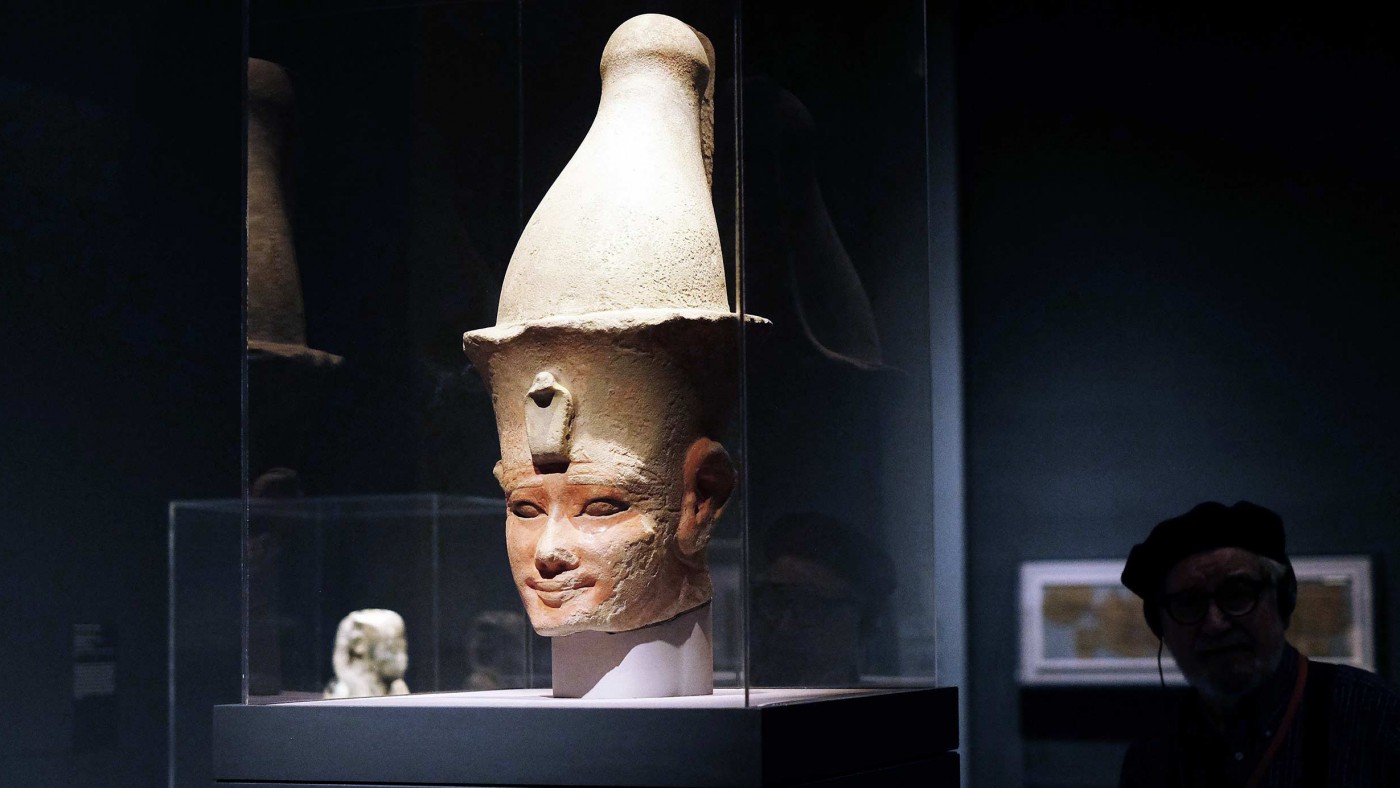

The exhibit is certainly extensive, spanning six rooms arranged by theme. Visitors can trace a path through Egyptian identity, admiring full-sized sarcophagi, depictions of deities, and charms to protect women in childbirth. But while these artefacts are impressive, it was one of the smaller rooms early on which drew my attention. This room took as its subject the facial expressions of the Middle Kingdom’s pharaohs.

It had never occurred to me that there could be some artistic choice behind the stylised features carved in quartzite and granodiorite. My appreciation of Egyptian statues had previously focussed on the ornate headdresses or the towering poses. But, as this exhibition demonstrates, the cultural shift in Egypt’s attitude to power is played out on the faces of the great leaders.

Egyptian religion regarded Pharaohs as the sons of the gods, and statues from the Old Kingdom depict them with smooth, mask-like faces, showing no trace of age or personality. This all starts to change in the Middle Kingdom:

“Egyptians were fully aware of the fact that kings were human, and Middle Kingdom art reached its peak expressing their dual nature… [Pharaohs] of the later Twelfth Dynasty present unforgettable royal faces reflecting the ruler’s intrinsic humanity.”

As I walked among statues, the stances and crowns may have been similar, but the faces were distinctly individual. Wrinkled skin, sagging cheeks and furrowed brows all suggested rulers with more wisdom and experience than their ageless counterparts from the previous era. Some even combined older faces with youthful bodies, implying both physical strength and sophisticated judgement.

This shift from godlike and anonymous to human and recognisable occurs in reverse in early imperial Rome two thousand years later. As Tom Holland describes in a book recently reviewed on CapX, the Emperor Augustus was portrayed with smooth skin and youthful features until he died at the age of seventy-five. Depicting Rome’s rulers as celestial figures was key to transitioning from a Republic to an Empire and maintaining power. In Egypt, showing the more human side of their rulers reveals a development in how authority was construed. What commands more respect, a leader with the wisdom of maturity, or a super-human emissary of the gods?

In the adjacent gallery, heads were turned by Monet’s waterlilies, Van Gough’s cornfields and Degas’ ballerinas. While not nearly so eye-catching, the Ancient Egypt Transformed exhibit reminded me of something far more fundamental than the impressionists romantic brushstrokes. For as long as humanity has been making art, artists have questioned the role and manifestation of power.