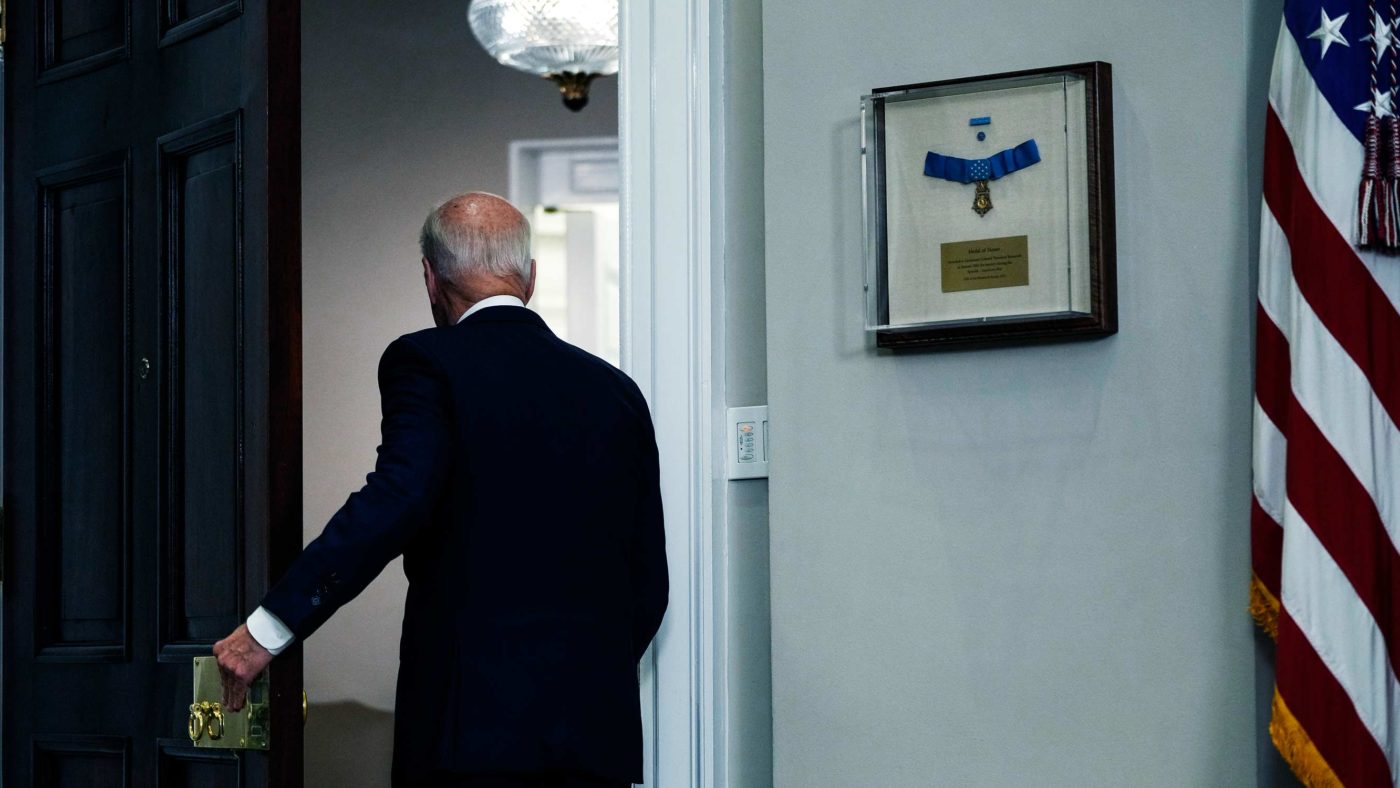

For all the speculation about the damage Donald Trump’s erratic personality did to America’s credibility, the sight of a Chinook departing the US embassy in Kabul feels like a far harder blow. After 20 years, $2 trillion spent, 800,000 serving soldiers deployed, and 2,352 deaths, America is leaving Afghanistan as it found it: under the control of the Taliban.

When the G7 met yesterday to discuss how to behave towards the Taliban as it takes power, they were also evaluating how to treat the United States from now on. The spectacle of America’s allies in this conflict – including Britain, France, Germany, and Italy – scrambling to evacuate nationals while being refused an extension to the deadline will live long in political memories. Joe Biden’s triumphant claim that ‘America is back’ was correct, but not in the way European nations thought it was.

When you are a global superpower it can be hard to commit to a course of action. America acts as America wants to at any given point in time, and for the most part there is little any other country can do to stop it. Its commitments are only as strong as its will to engage, and in turn the domestic pressure on the commander-in-chief to maintain or divert from a course of action.

When America looks to commit, it needs to either create costs for deviating which are large enough to discourage it, or to have a long-term interest in maintaining cooperation by other players. The rules-based order falls into the latter category; Nato’s ‘tripwire’ forces in the Baltics belong to the former.

Even strong initial commitments can wear out in time as public opinion shifts and political dynamics change. Ukraine was persuaded to give up its nuclear weapons with the promise that Russia and the United States would refrain from the use of force against it and would ride to the rescue if it were threatened. When Russia subsequently annexed Crimea, America did nothing. The commitment it made was broken because the costs of upholding it became too high.

The primary danger associated with these shifts is that your opponents or allies may start to draw correlations between theatres and causes that may not exist. The Chinese Admiral Lou Yuan observed in 2019 that ‘what the United States fears the most is taking casualties’, and speculated that America’s will would break with the first significant losses in a conflict with China. America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan has already been claimed by Beijing as a signal of Washington’s unwillingness to fight for Taiwan.

No matter how shambolic the operation has been, it may be a mistake to conclude that a long-awaited drawdown from Afghanistan implies a lack of willingness to fight elsewhere. That does not change the fact that it invites speculation. If Beijing could strike quickly enough to roll over the Taiwanese military, would America have the national will to fight a bloody campaign to retake the territory?

When America says it will stay the course no matter the cost, it needs the people on the other side of the table to believe it. When America is unwilling, its allies and opponents can work around it knowing how it will behave. When America is unpredictable, people can miscalculate catastrophically.

A less abstract problem is that as coalition forces depart and leave Afghan workers to their fates, this behaviour will be noticed by people who might be asked to co-operate with American military ventures in the future. Who would act as an interpreter in the knowledge that 10 years down the line you would have no offer of safety in return for your service?

Similarly, America’s allies who joined it in the war have found themselves held to a timetable not of their making, with the Biden administration unwilling to accommodate their needs. In some ways this has merely highlighted an already extant dynamic that Western strategy revolves around the United States and runs on Washington time, but by illustrating that America is making decisions unilaterally Biden has, to quote one US columnist, ‘humiliated his Western allies by demonstrating their impotence’.

It’s one thing for Britain’s military strategy to be ‘allied by design’. It’s another for our capacity to be so atrophied that Defence Secretary Ben Wallace shifted in a matter of days from attempting to gather a coalition of other Nato forces to remain in Afghanistan to conceding that we can’t hold Kabul Airport alone.

The most high-profile success for Britain’s forces in the absence of American front-line support is the UK-France intervention in Libya, and this could not have gone ahead without American supply chains, American surveillance, and American co-ordination. Dependence on the United States is tolerable when Britain and Europe believe America is committed to them and that its interests are aligned with theirs. It is not when America is turning in on itself.

The lack of a feasible alternative to reliance for security in the short run means that there is unlikely to be lasting damage done to European cooperation by the Afghanistan withdrawal. Over a longer period, however, it remains an incentive to avoid engaging with new ventures overseas, and to look to create greater domestic capabilities.

Finally as the world recalibrates, it is worth thinking about how American strategy accommodates the reliance of the US commander-in-chief on domestic public opinion – in other words, how much confidence it should place in its future self.

As the British diplomat Robert Cooper observed in 2000, ‘nobody wants to pay the costs of saving distant countries from ruin’. Moreover, ‘because wars fought for other people are difficult to sustain in domestic opinion, one may end up not even saving them’. But when the last helicopter leaves, the original problem remains: ‘the pre-state, post-imperial chaos’ has a way of spreading; the unordered areas of the world becoming havens for drug growers, terrorists, and other criminals. If nation-building is not the way forward for America, what is?

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.