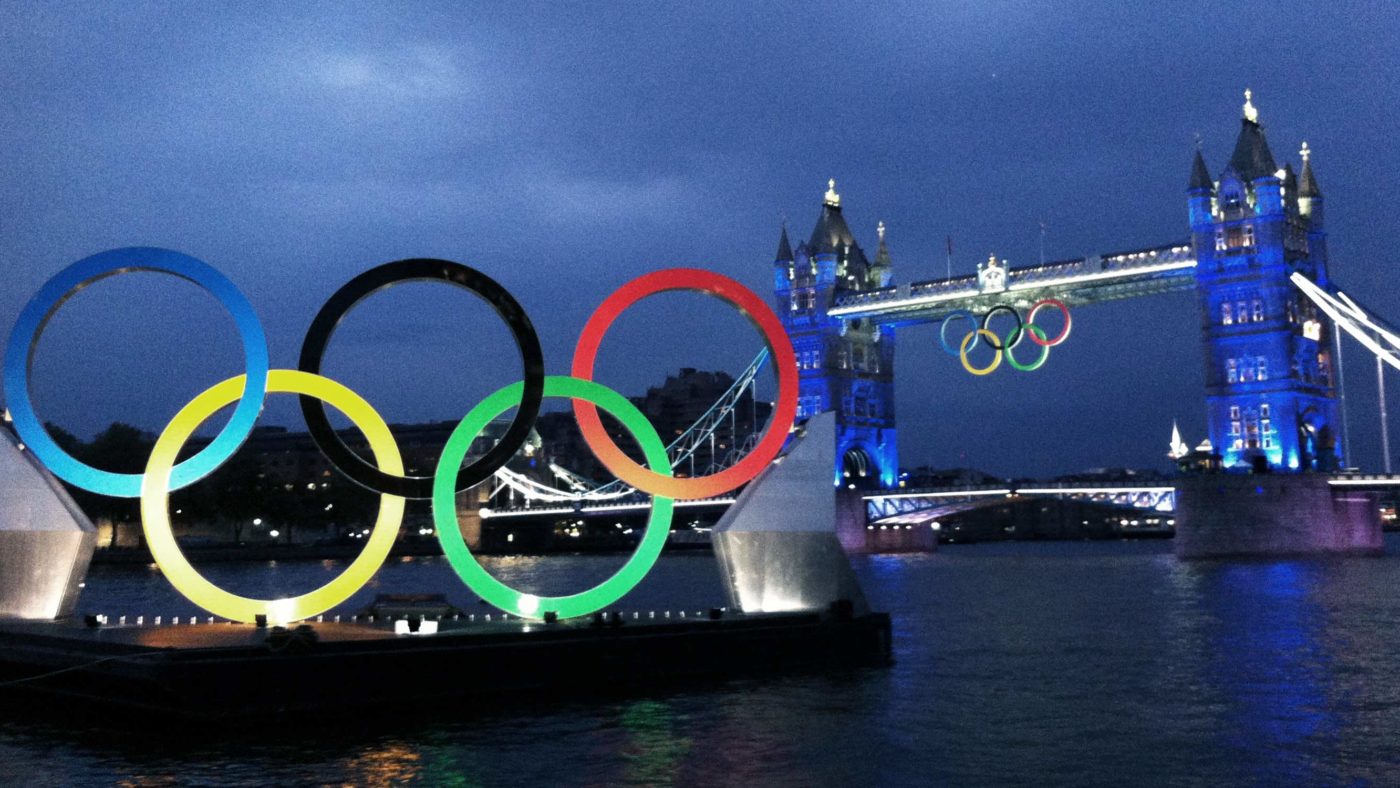

It’s exactly 10 years to the day since the opening ceremony of the London 2012 Olympics. While at the time there was much fanfare about a moment of national unity after the awful post-crash years, the longer term legacy of the Games ought to be subject to close scrutiny.

Before 2012, there was certainly a clear enough idea of what the Games would achieve, both locally and for the UK as a whole. Ken Livingstone, who was Mayor of London at the time of the bid, saw the event as a golden opportunity to secure vast amounts of public investment for a neglected, relatively deprived part of east London.

There was also a broader mission to use the Games as a way to boost take-up of sport. Indeed, the day the capital won the bid, then prime minister Tony Blair told the International Olympic Committee he wanted ‘to see millions more young people in Britain and across the world participating in sport and improving their lives as a result of that participation’.

A decade on, how much of that has materialised?

On the sporting front, it was little short of a triumph. Team GB won 65 medals, of which 29 were gold – our most successful Olympics performance since the 1908 Games (hosted in the same city, incidentally). ‘Super Saturday’ was truly exhilarating, with heptathlete Dame Jessica Ennis-Hill, long-jumper Greg Rutherford and long-distance runner Sir Mo Farah all winning gold medals in the space of an hour.

But there is a dark underbelly to the Olympics that tends to go unnoticed, even by residents of the host cities themselves – industrial-scale gentrification and population displacement. A report published by the Centre for Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE) concluded that between 1988 and 2008, the Games had contributed to the displacement of more than 2 million people in host cities, with property price inflation one of the driving factors. Event-led local economic regeneration, state-sponsored gentrification and the displacement of existing residents are all too often intertwined – and London 2012 is no different.

As early as 2013, Dr Paul Watt of Birkbeck, University of London wrote on the wholesale social, economic and physical transformation of deprived inner-city areas – increasingly driven by large-scale regeneration projects such as London 2012. Local people in working-class neighbourhoods have not necessarily welcomed such changes – with many younger residents being shut out of the housing market in areas where they were born and raised.

Last year, Nationwide Building Society reported that all six Olympic host boroughs – Newham, Hackney, Waltham Forest, Tower Hamlets, Greenwich and Barking & Dagenham – had seen house prices rise by more than both the London and UK average. Waltham Forest recorded the biggest increase, with a stunning uplift in average house prices since 2012 of over 100%. Of course, it would be churlish to attribute that inflation to the Games alone, but there’s little doubt that for working class east Londoners aspiring to get on the housing ladder, the fallout of London 2012 has not been favourable.

Nor has the Games left a positive legacy for small, independent local businesses. Writing in the Journal of Place Management and Development, academic Mike Duignan found ‘a local legacy of small business failure fuelled by rising commercial rents and a wider indifference for protecting diverse urban high streets’. Local SMEs have struggled to stay afloat as monochromatic chain stores moved into east London, pushing up rents and contributing to what has been pithily described as an ‘urban blandscape’.

But what about the ‘participation’ Tony Blair was so enthusiastic about?

Well, it didn’t seem to make much of a difference to the areas that actually hosted the Games. The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) found that the London 2012 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games had only ‘small and transient effects on physical activity, mental health and well-being for those living nearby’. Although local access to new sporting facilities and high-quality green spaces can be improved by event-driven urban regeneration projects, the study concluded that this may not lead to ‘sustained improvements in physical activity, mental health, or well-being’. It follows that policymakers should take care before making grand claims that large-scale sporting events are an effective way to improve physical well-being and mental health outcomes in host areas. At best, it provided a short-term burst of excitement and a temporary respite from the everyday stresses of life – with an extremely high price tag.

All of this matters because London is once more in the mix to host the Olympics, with a bid for the 2036 Games apparently under consideration. If the capital does end up hosting the Games for a third time, whoever is in government must be sure to heed the lessons of 2012, look beyond the razmatazz of the opening ceremony and the medal ceremonies, and think long and hard about the impact such events can have on the local population.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.