Occasionally, an article comes along that is so perceptive, that has such an air of rightness about it, that reading it is like hearing one of those Mozart melodies that seems to have been plucked fully formed from the ether rather than constructed by human endeavour.

Such is Robert Kagan’s column in the Washington Post, ‘Trump is the GOP’s Frankenstein monster. Now he’s strong enough to destroy the party’. Kagan is never not interesting – he is, of course, most famous as one of America’s senior neocons (or, as he prefers it, liberal interventionists). He has a habit of spotting things early – his 2003 book ‘Paradise & Power: America and Europe in the New World Order’ nailed the sharply diverging worldviews and interests of those two mighty blocs; ‘The Return of History and the End of Dreams’ beautifully synthesised the myriad challenges facing a West grown dangerously complacent.

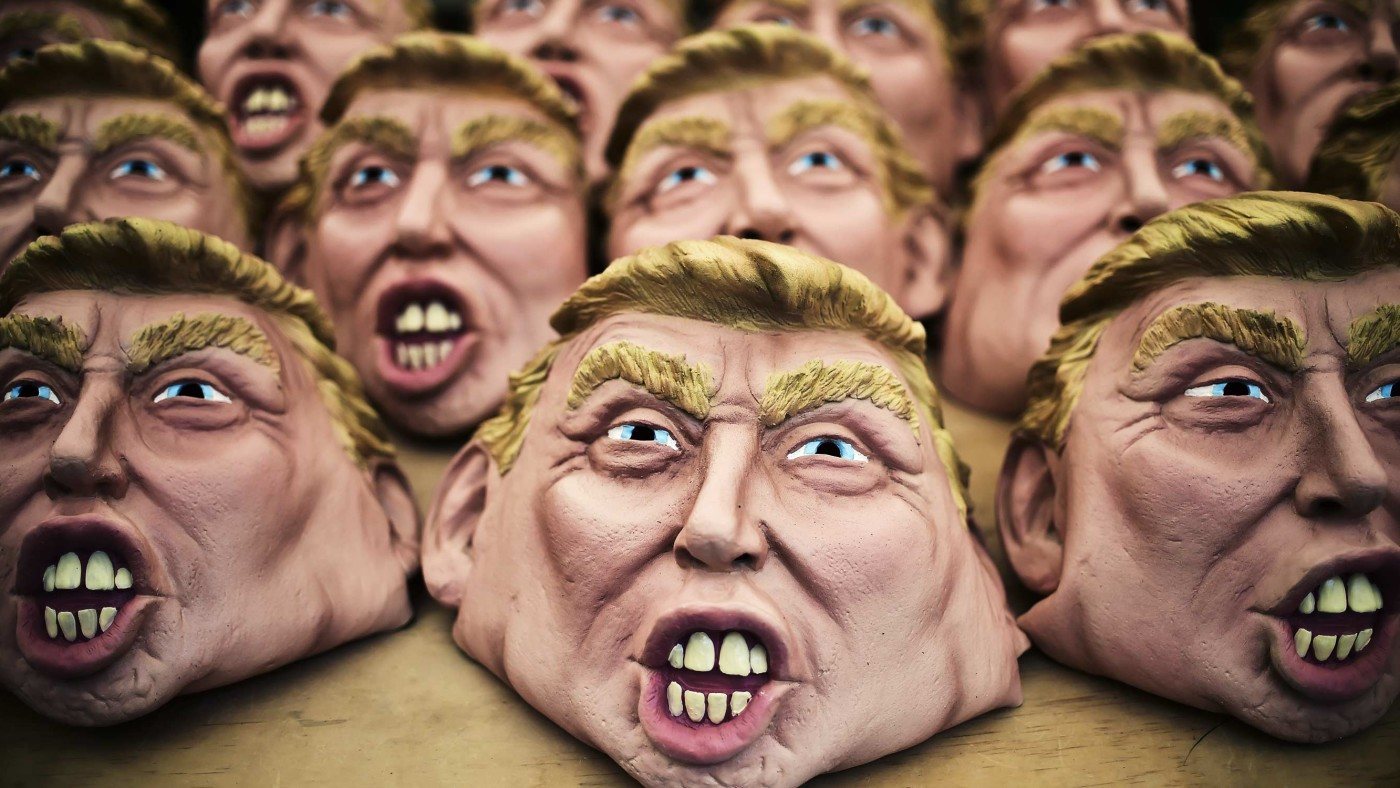

Kagan has drifted apart from the Republican Party, and it is perhaps this ‘sinner’ repenteth approach that has allowed him to address the Trump phenomenon – ‘the most successful demagogue-charlatan in the history of U.S. politics’; an ‘anarcho-revolutionary’ – with such clarity.

I urge you to read his piece in full, but its key points are as follows:

• Trump isn’t a fluke, but rather an inevitable consequence of Republicans’ ‘repeated threats to shut down the government over policy and legislative disagreements, the persistent calls for nullification of Supreme Court decisions, the insistence that compromise was betrayal, the internal coups against party leaders who refused to join the general demolition.’

• This ‘taught Republican voters that government, institutions, political traditions, party leadership and even parties themselves were things to be overthrown, evaded, ignored, insulted, laughed at…’

• For years, the party’s grandees have accommodated and exploited bigotry within its ranks. ‘What did Trump do but pick up where they left off, tapping the well-primed gusher of popular anger, xenophobia and, yes, bigotry that the party had already unleashed?’

• ‘We are supposed to believe that Trump’s legion of “angry” people are angry about wage stagnation. No, they are angry about all the things Republicans have told them to be angry about these past 7½ years, and it has been Trump’s good fortune to be the guy to sweep them up and become their standard-bearer. He is the Napoleon who has harvested the fruit of the revolution.’

On this side of the Atlantic, the infarction of US politics has been obvious for years. For those British Conservatives willing to see it (those who didn’t feel honour-bound to defend the latest lunatic Republican tactic or grotesque misrepresentation or constitutional outrage; those who didn’t argue Sarah Palin and the Tea Party movement were simply misunderstood), it has been like watching a much-loved and inspirational relative go through a nervous breakdown. The Right’s (and it is largely the Right) apoplectic, spittle-flecked rage against so many aspects of modernity, against demographic change and legitimate Democratic majorities, against people who happen to hold a different view, has at times seemed to spill over into an all-out assault on the very concept of liberal democracy.

Perhaps too late – way too late – there are signs at last of an awakening of sorts, of a restoration of self-awareness. David Brooks, the New York Times’s eminent conservative writer, used last week’s column (also worth reading in full) to spell out the basic principles of a healthy, pluralist politics.

‘It is an activity in which you recognise the simultaneous existence of different groups, interests and opinions. You try to find some way to balance or reconcile or compromise those interests, or at least a majority of them. You follow a set of rules, enshrined in a constitution or in custom, to help you reach these compromises in a way everybody considers legitimate.

‘The downside of politics is that people never really get everything they want. It’s messy, limited and no issue is ever really settled. Politics is a muddled activity in which people have to recognize restraints and settle for less than they want. Disappointment is normal.

‘But that’s sort of the beauty of politics, too. It involves an endless conversation in which we learn about other people and see things from their vantage point and try to balance their needs against our own.’

One’s first reaction is that it’s staggering something as obvious and basic needs to be said at all, and especially in a democracy as elegantly designed as America’s. Next comes a creeping chill that an observer as astute as Brooks is likely to be right that it does.

He goes on to point out why: the rise of ‘anti-politics’, of a group of people who ‘delegitimise compromise and deal-making… They’re willing to trample the customs and rules that give legitimacy to legislative decision-making if it helps them gain power.’ Needless to say, this is the opposite of conservatism.

Brooks describes this as a form of political narcissism, in its refusal to accept the legitimacy of other interests and opinions. It is about ‘total victory’.

As ever, when the US sneezes, we all of us catch a cold. The rise of intra-state unreasonableness, of do-or-die culture war politics, across Western democracies poses the gravest internal threat of our times. This weakens and distracts us from thinking hard and rationally about the external challenges we face, whether growing Eastern might, Russian adventurism, Islamist creep or climate change. It also stops us collaboratively addressing the flaws that are now so obvious in our liberal-capitalist settlement.

Perhaps the sheer unthinkable, shaming awfulness of a potential Trump presidency will do the job – will force the US to look into the abyss and, finally, take a good few steps back. Who, these days, though, would bet against them jumping?